When I wished I was Robert

Back in the late 90s, when Robert Alejandro and I were both working as hosts on The Probe Team, a young stranger came up to me with a piece of paper in a public place and asked me to draw him.

I knew exactly whom he thought I was, but I decided to play along. Having absolutely no talent in drawing, I drew a crude stick figure with a smiley face and handed it back to the fan, who reacted with a look of utter dismay, as if his hero had just betrayed him as an inept phony. I felt guilty and sorry for him so I blurted out that I was not THE Robert Alejandro and laughed out loud. He didn’t find it funny and left in a huff.

When I told this story to Robert in our last conversation, he did find it funny.

Then we both riffed about a theory that in our world of distractions, people on TV begin to look alike.

Now that I think about it, just a few days after Robert left us, maybe that’s not why his fan mistook me for him. After all, we didn’t look at all alike, he with the much lighter complexion and broader smile.

Perhaps it’s the feeling of public awkwardness that Robert and I would confess to each other, which we probably projected in subtle but obvious ways.

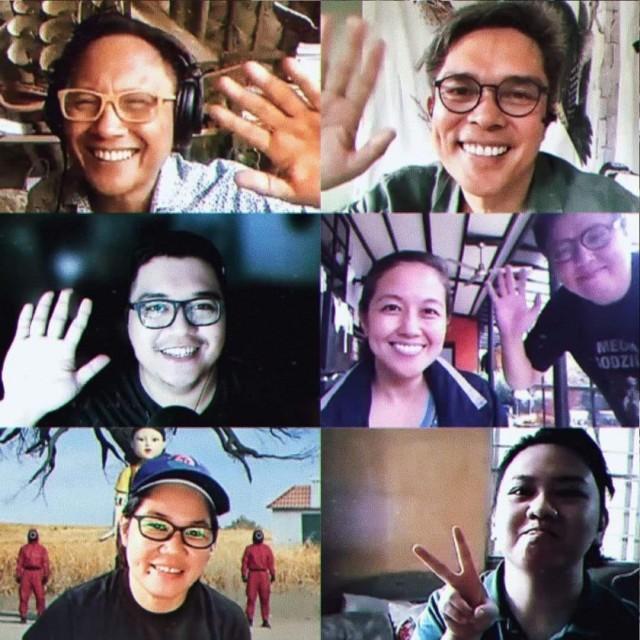

(Top right) November 2021, at the end of a podcast interview with Robert Alejandro. Photo courtesy of Howie Severino

You see, we were both accidental, mid-career migrants to television, as Probe Team hosts, around the same time in our 30s after a series of other jobs, him in art and advertising, me in print journalism. As an artist and a newspaper reporter, respectively, we were both used to working long hours alone and walking around in public totally unrecognized.

Neither of us considered himself a natural on TV, but we were amply tutored in voicing and other aspects of the job by our savvy TV producers at Probe, all of them younger than us and already veterans after entering TV soon after college.

After years as solo practitioners in our fields, Robert and I found ourselves working with teams nearly all the time. It was a mind shift and new lifestyle we adopted with gusto, as an opportunity to reach wider audiences as well as forge deep friendships with new and younger colleagues.

At The Probe Team, Robert got a unique gig as the traveling host with a sketch pad, engaging the world through his art. It was a gloriously appealing brand and provided an embarrassment of riches for producers weaving visual elements into narratives. Besides, everyone soon learned that Robert was a joy to be with.

As part of the “late boomer generation,” Robert and I raised the staff’s average age substantially when we became Probers. But Robert was anyone’s equal in child-like enthusiasm, and always earnest and gentle even when he had to give critical feedback about our work.

Through it all, Robert never forgot our common roots as awkward newbies. He was one of the few who got my wry sense of humor, as in deadpan sarcasm which would cause him to chuckle. More than once, I would overhear him tell our colleagues, “Howie is really funny!” As if he had to convince skeptics that I did have a funny bone.

After a few years, he graduated from The Probe Team and was given his own show, Art is Kool, which morphed him into Kuya Robert, a new vocation as art teacher ng bayan, engaging kids of all ages whether on camera or off. I so much wanted to be him when that kid approached me innocently asking for his own portrait by Kuya Robert.

With his show, the world then saw what his colleagues and friends already knew: Robert had a deep well of empathy, perhaps deeper than any other we had come to know.

Since he exuded the sense of not having a malicious cell in his body, I surmised that more than a few, like me, trusted him to be a moral compass. If Robert cared about something, then it must be worth caring about and even advocating. And Robert cared about many things aside from children and fellow human beings. He loved animals and especially wild birds. He drank in other cultures as a travel junkie. And he was a patriot and made committed political choices.

After he got sick and began sharing his pain on Facebook, I sent him a plant that I grew and potted myself as a fledgling plantito. It was the height of the pandemic and we couldn’t go out, much less visit anyone with multiple morbidities like Robert at that time.

Much to my surprise, since I knew he was suffering, he sent me in return a package that included a stylized version of a vintage map of the Philippines printed on fabric, resembling the same 1734 map that was submitted to The Hague as proof of Philippine sovereignty in the West Philippine Sea. He of course designed the product and wrote me that it wasn’t in the market yet.

He was the creative brains behind his family’s crafts shop, Papemelroti, in Quezon City, which was full of such surprises, gift items like hand fans and magnets with his signature exuberant designs that celebrated Philippine heritage and culture. I’ve visited that shop on Roces Avenue often through the years, but especially during the pandemic when we’d just read about Robert’s struggles. In that quirky, colorful shop while in the depth of our universal despair, I’d imbibe Robert’s upbeat vibe but also feel that his newer creations were messages to his personal friends and to himself as well, like the flowery magnet with the words, “The best is yet to come.”

In the hours after Robert’s death was announced last Tuesday, my social feed teemed with portraits and other art that he sent to friends as gifts or quickly made to comfort those who had just lost loved ones. Art was truly his love language.

Howie and Robert in 2004. Photo courtesy of Howie Severino

Our last conversation in November 2021 was on zoom, when most of us were still physically isolated from each other. The call was for my podcast, an excuse to ask him just about anything. He looked and sounded great, and I told him so. He said he was a “walking miracle” because he was finally pain-free even if his cancer had not abated, crediting a special daily diet prepared by his devoted partner Jetro. He was making plans for an exhibit and a book. As we all know now, that golden, pain-free interlude was short-lived.

We did also talk at length about his battles, including the mental torture of self-doubt in his younger years. But he had now fully accepted himself and was at peace.

I never knew of those earlier struggles. I had only known the Kuya Robert who made many kids happy and the colleague who brightened even our most stressful days.

Before we talked about both growing old at the same time, he recalled our early friendship when we entered television together as overage rookies. “You were being assigned all this hard-hitting stuff, and I remember at one staff meeting, you were kind of complaining,” he said, snickering at the memory. “You said, ‘why can’t I also do what Robert’s doing?’”

I’ll never be able to do Robert’s style of storytelling, combining artistic genius with child-like wonder. But I can strive to live like him, with gentleness, kindness, and ultimately acceptance and even gratitude for whatever life has in store for me.

Robert Alejandro

1963-2024

—JCB, GMA Integrated News