Beyond the Final Frontier: ‘Star Trek’ at 50

Part 1 of 2

Over 50 years, six television series (with one more on the way next year), 13 feature films, a plethora of merchandise, and one of the most dedicated fan bases in all of pop culture, “Star Trek” is a genre juggernaut in every sense of the word – but it certainly didn’t start out that way.

On September 8, 1966, the original “Star Trek” television series debuted on NBC. The brainchild of former pilot and police officer-turned-TV-producer Gene Roddenberry, “Star Trek” told the story of the Starship Enterprise and its five-year mission to explore the universe under the command of the indomitable Captain James T. Kirk.

As played by William Shatner, Kirk was a man driven by his profession as much as his impulses, settling alien disputes with fists and wits in equal measure. He was also, as the recent rebooted films have shown, a dyed-in-the-wool ladies’ man who didn’t let little things like planets of origin get in the way of his interstellar dalliances.

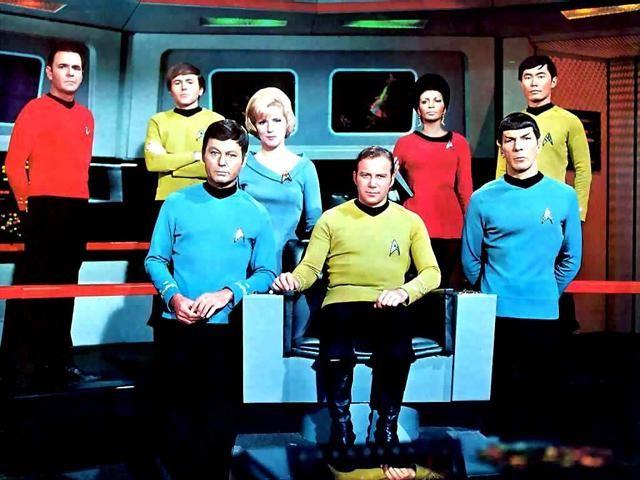

Serving under Kirk was a dedicated, highly-trained crew featuring characters that have since become the stuff of pop culture legend, including half-Vulcan science officer Spock (Leonard Nimoy), crusty ship’s surgeon Dr. Leonard “Bones” McCoy (DeForest Kelly), chief engineer and all-around miracle worker Montgomery “Scotty” Scott (James Doohan), navigator Pavel Chekov (Walter Koenig), helmsman Hikaru Sulu (George Takei), and communications officer Uhura (Nichelle Nichols). With characters including an Iowa farm boy, an alien, a southern physician, a Scotsman, a Russian, a Japanese, and an African American, Roddenberry’s vision of an integrated future where gender and cultural background were secondary to one’s competence wasn’t just progressive, it was downright revolutionary.

From the beginning, Roddenberry promoted “Star Trek” as being based on science fact, rather than science fiction. Despite the heroes’ being decked out in primary colors (to help promote color TV sales) while exploring alien environments that one could charitably call flimsy, “Star Trek” stood out for taking its premise seriously—this was no gimmicky kids’ show, nor was it a farce like “Lost in Space”. Production limitations notwithstanding, “Star Trek” resonated with its audience by being about people and ideas rather than hardware or visuals.

Nowhere was this more apparent than the onscreen friendship between Kirk, Spock, and McCoy that formed the emotional core of the show. Between Kirk’s archetypal brashness (body/id), Spock’s dispassionate alien logic (mind/superego) and McCoy’s humanistic outlook (heart/ego), the manner in which the “big three” would play off and complement each other to face whatever challenges the unknown could throw at them were infinitely more engaging than any number of special effects or action sequences.

This isn’t to say that “Trek” didn’t have its own agendas; this was, after all, a show produced at the height of America’s civil rights movement, the Cold War against the Soviet Union, the Vietnam War, and the actual US space program to put a man on the moon. By virtue of setting his show in space in the far-flung 23rd century, Roddenberry could get away with commenting on conflicts, prejudices, and issues in the largely conservative landscape of 1960s TV.

Whether it was racism based on the color of one’s skin (two-toned aliens), the perils of interfering in other states’ political affairs (leading to the creation of Starfleet’s Prime Directive of non-interference), or the delicacies of détente (with Klingons and Romulans standing in for the communists). It was rarely subtle, but given the sensibilities at the time, it was as cutting edge a commentary as could be found in entertainment designed for a mass broadcast audience.

The show’s format also allowed for flexibility as far as genre was concerned, giving the actors a wide variety of material to play with, whether it was dramatic (“Let That Be Your Last Battlefield”), thrillers (“Balance of Terror”, “The Doomsday Machine”), comedy (“The Trouble with Tribbles”), or even a dig at classical mythology (“Who Mourns For Adonais”). By far, the Original Series’ finest entry was Hugo Award-winning time travel story “City on the Edge of Forever”, based on a story by legendary sci-fi author Harland Ellison.

Midway through its first season, despite being generally well-received, “Trek” faced a stumbling block in the form of threatened cancellation from network NBC, which cited low ratings. Through a letter-writing campaign spearheaded by dedicated fans and established genre authors, NBC received one million pieces of snail mail petitioning to save the show. The campaign was a success, and one of the first instances of fans uniting to make their opinion heard—a major accomplishment in the days before social media.

However, ratings didn’t improve for Season 2, and a timeslot change in Season 3 to Friday nights at 10pm led to even lower ratings and, ultimately, cancellation in 1969. With their TV voyages at an end with 79 episodes, the cast went about looking for new work. But then something curious happened: In the early 1970s, with the proliferation of decentralized TV stations in the United States, there emerged a demand for packaged seasons of series, which the national broadcasters were all too happy to provide (for a fee). In much the same way that today’s cable channels run old sitcom episodes daily, “Star Trek” started being sold to fill empty timeslots on regional and local tv channels.

Through syndication, the program received greater exposure than it ever had and, in the process, picked up new fans. Now broadcast daily at different times on a number of channels throughout the country, “Star Trek” would go on to enjoy greater popularity after being cancelled than it ever did when it was on NBC.

It was around this time, when no new material was being produced, that fandom as we know it came into being, as fans began taking ownership of their beloved show, self-publishing their own magazines (fanzines). These would be filled with simple artwork and fan fiction, along with behind-the-scenes anecdotes and images acquired from the conventions that fans had begun organizing on their own. These conventions would include screenings, homemade merchandise for sale, and cosplay contests, with the main attractions being having former cast members appear onstage to speak about their experiences.

The legacy of these early events can be seen in the multiple Star Trek conventions arranged throughout the world to this day, which attract thousands of attendees, or the likes of the annual San Diego Comic Con, where celebrities appear in panels before gathered fans to discuss or answer questions about their projects.

With the new wave of popularity, an animated series was commissioned in 1974 with Roddenberry at the helm that reunited most of the original cast (sans Koenig) to voice their characters. Running for two seasons, Roddenberry treated “Star Trek: The Animated Series” as if was a new season of the live action show, to the point of employing many of the same writers to craft episodes. True enough, thanks to storytelling significantly more intelligent than the average Saturday morning cartoon fare, “Star Trek’s” animated spinoff won an Emmy for writing.

By then, “Star Trek” had well and truly become a part of the zeitgeist. In 1976, a fan letter writing campaign convinced US President Gerald Ford to rename NASA’s upcoming prototype for the space shuttle from Constitution to Enterprise. So it came to pass, seven years after their live action TV adventures had come to an end, the Star Trek cast of fictitious space explorers was reunited by NASA and given a hero’s welcome at their shuttle’s official dedication ceremony.

Who would have thought?

With mainstream awareness and recognition coming so long after the fact, the “Star Trek” story could very well have ended on a positive note of vindication right there and then. However, Gene Roddenberry wasn’t done with his creation just yet, though, to be perfectly fair, nobody could ever have predicted that the release of a film called “Star Wars” in 1977 would go on to influence the big screen future of the good ship Enterprise.

Next week in Part 2: Cinemas, sequels, and spinoffs, as “Star Trek” begins on the road to becoming a pop culture phenomenon.