How I became a Filipino: A guide to naturalization for fellow foreignoys

"Ay! Nagta-Tagalog ka pala, na-nosebleed pa 'ko!"

That's the usual line I get when people speak to me in English and I respond in Filipino.

I would then have to explain that I wasn't really Filipino — even though I was born here (where jus soli — acquisition of citizenship through place of birth — is not in effect) and even though I speak the language fluently. Neither of my parents are Filipino and I'm not married, so aside from being Pinoy "sa puso, sa isip, sa salita at sa gawa," I still wasn't legally a Filipino.

That is, until now. After 26 years of breathing Philippine air (not to mention countless adobo recipe attempts), I am finally, legally, without a doubt, a Filipino citizen.

My year-long affair with the Office of the Solicitor General’s Special Committee on Naturalization (OSG-SCN) wasn’t a piece of cake. More than the actual exam and interview, the process itself from start to finish is the ultimate test of how much you want to be a Filipino citizen.

Before you embark on this long, rigorous process, here are some tips that might save you some time and effort. I did all of these without the help of lawyers (although you can hire one), fixers (please don't hire one), connections, or any kind of under-the-table negotiation.

SEPTEMBER 2014: Sana Dalawa ang Puso Ko

My dad had been nagging me for the longest time to inquire about the naturalization process that many of our fellow foreignoys had undergone and many of our immigration assistants are recommending we go through. This process will enable us to own property and businesses, to vote, to go out of the country without having to pay immigration, to travel to ASEAN countries without a visa, among other things.

Giving up my Indian citizenship seemed like I was revoking something I had neither fully understood nor utilized. I have been to my parents' homeland only three times thus far. (Of course "home" and "land" are up for discussion as my family has a history of migration after a portion of India decided to become Pakistan — the portion of which both my grandparents are from — but that's a different story.)

India does not allow dual citizenship but upon further research, I found that I was qualified to be an Overseas Citizen. The Indian culture is alive in our home and I will forever be in touch with my colorful roots.

In the end, the deciding factor to become Filipino was simple: I wanted to vote. I wanted to actively participate in a community where I felt I could really thrive and contribute the most — and I wanted to be able to do these without the technical and legal barriers.

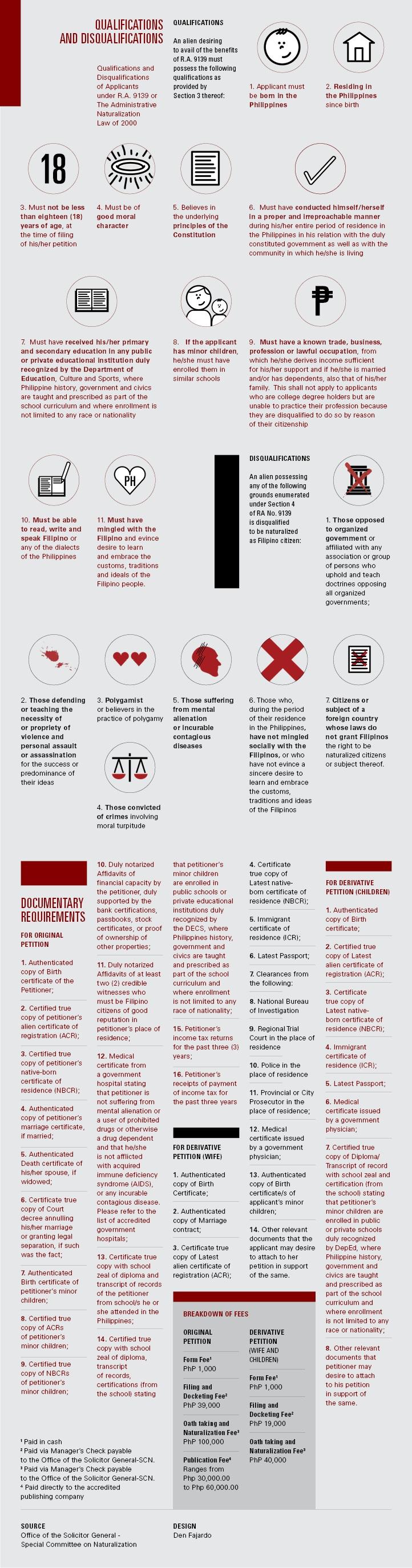

Whatever your own reason may be, make sure to check first if you are qualified under Republic Act No. 9139 or the Administrative Naturalization Law of 2000. The application form costs P1,000 — the first of many payments you’d have to make in more or less a year.

OCTOBER 2014: Itanong Mo Sa Akin Kung Sino ang Aking Mahal

When it was my turn to pay for a clearance at the NBI head office in Manila, I remember the girl looking at my form and asking me: “Naturalization talaga? Gusto mo talaga maging Pilipino? (You really want to be Filipino?)”

Opo, ate.

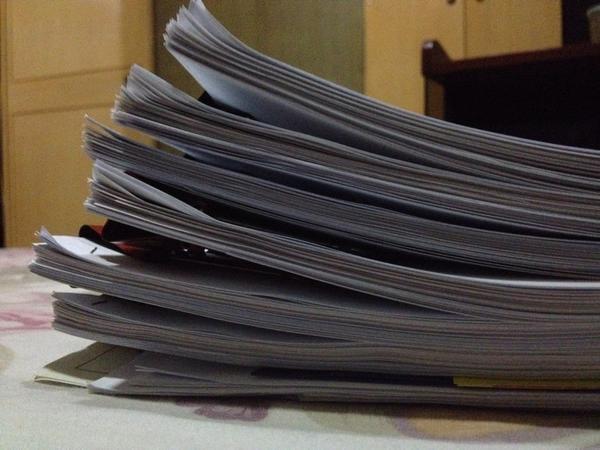

At this point, I had asked a lot of people about the process but I didn’t know for sure if I was doing the right thing and just wished for the best. It took me about a month to compile all the clearances. So don’t waste time and get on with those applications right away.

Make sure you have access to a typewriter (and have ample supply of correction fluid) as the form needs to be typewritten before being notarized, thumb-marked and photocopied six times along with other requirements.

Pay attention to details in the requirements list such as getting two witnesses that you’ve known for at least 10 years and who live in your city (not region). They will also be called in for an interview when you get through to the next step.

The very friendly and patient SCN clerks Maricar and Angel will tell you if you have sketchy or questionable documents even before you formally file them and it is important that they are addressed right away to prevent further complications. At this stage, you’d have to shell out P39,000 — this is regardless if the committee will grant or deny your petition.

DECEMBER 2014: Walang Makakapigil Sa Akin

Your petition will be raffled off to a publication, where pertinent portions of your petition need to be published once a week for three consecutive weeks. Anyone with a valid reason can oppose your petition, so you'd want to have a clean record and no enemies.

You would have to transact directly with the broadsheet assigned to you. Prices may differ depending on the publication. Mine summed up to P68,238.

MARCH 2015: Wish I May, Wish I Might Find a Way to Your Heart

The SCN will gather your clearances from different government agencies. Oddly enough, I had to go through the National Statistics Office (NSO) on my own and pay an additional fee.

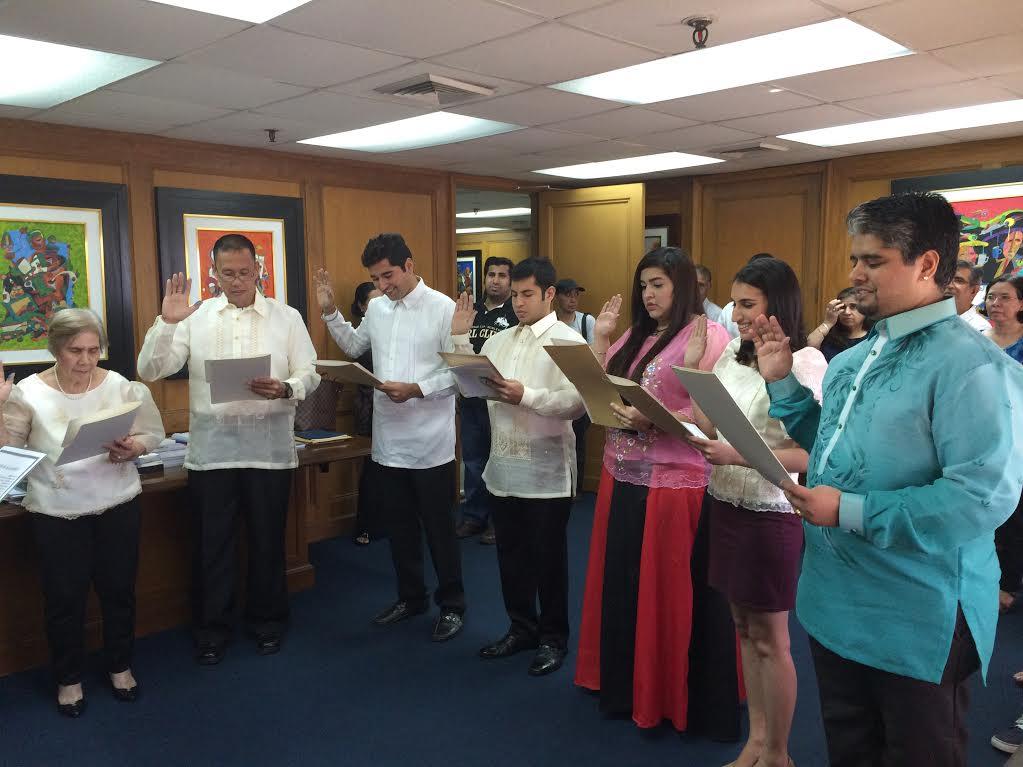

Afterwards, the SCN will call you individually for testing and interview you along with your witnesses. This made me nervous: How will you prove your Filipino-ness to a stranger in just a couple of hours?

My hand hurt from answering 10 seemingly simple essay questions that ranged from Philippine history to current issues to salawikain. The interview with the OSG lawyer assigned to my case was about what I had already written in my petition, the test I took, and other personal questions.

The waiting part after what I dubbed the "How Filipino Are You" trial is the most nerve-wracking part for me. My overthinking self got a bit paranoid: Did I say something senseless in the interview? Do I need to pay extra fees? What if they didn’t like me? I called the SCN office almost every week to ask for updates and even tweeted SolGen Florin Hilbay for good measure.

NOVEMBER 2015: Ang Tamang Panahon

I looked at Papa from across the room during my oath-taking ceremony and thought about how far he had come. He was in my position more than 35 years ago, pledging his loyalty to the Philippines as a permanent resident.

Back then, there was a quota per nationality of how many immigrants will be granted permanent residency status. He was one of the 50 lucky Indians that year. He tells me this story as if it were yesterday.

This might just be another legal process to some but this is a game changer for me and my family. There is nothing an immigrant wants more than a sense of permanence and something more than a figurative home.

Unfortunately, my oath taking came 10 days after the last day of voter’s registration so I will not be able to vote in the 2016 presidential polls. Nevertheless, I am already thinking of ways I can be more involved in my community.

For now, a huge weight has been lifted off my shoulders — not to mention a huge chunk off my bank account - P100,000! — but I’m not stopping here. I’m off to get my maroon passport.

Gayna Kumar is a member of the GMA News Social Media Team. She is in no way affiliated with the Office of the Solicitor General or the Special Committee on Naturalization.

If in need of guidance or words of encouragement, she may be reached at gayna.kumar@gmail.com or via Twitter @gaynakumar. For OSG-SCN concerns, contact (+63) 2 893-02-00 or (+63) 2 988-16-63 or visit 134 Amorsolo St., Legaspi Village, Makati City, Philippines.