Throwback Theater: Roller coasters and racism in ‘Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom’

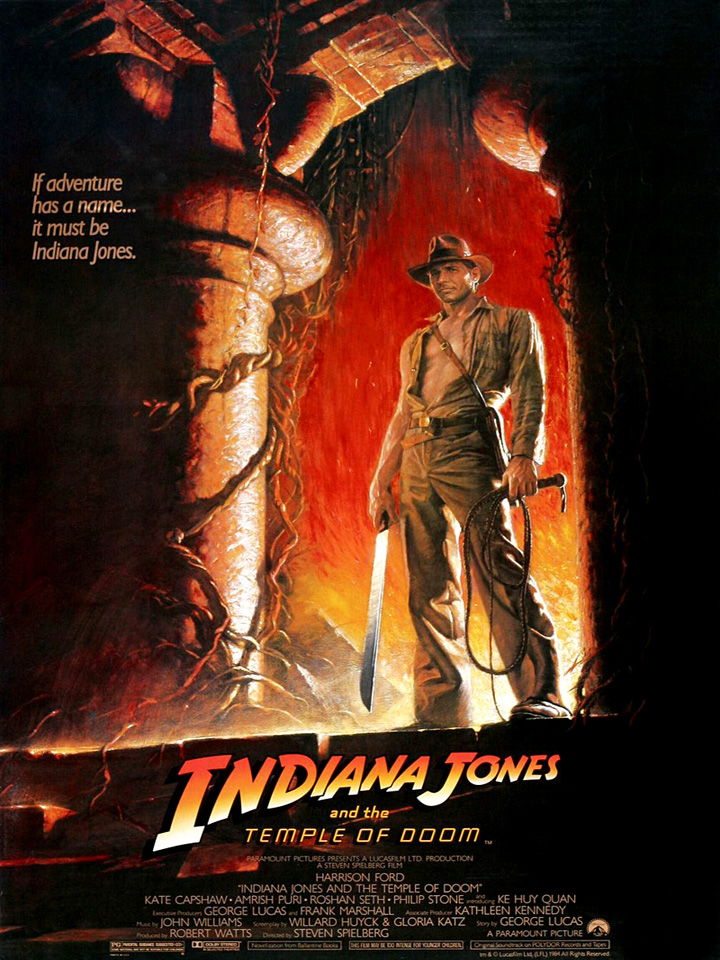

For many a moviegoer awaiting the sequel to 1981’s “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” the aforementioned image would be their first exposure to the audaciously-titled “Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.” If the now-iconic poster by Bruce Wolfe (or the equally gorgeous piece by Drew Strewzan that followed) wasn’t enough to get one’s attention, the delightfully hyperbolic (or not, depending on your point of view) text that accompanied it sealed the deal: “If adventure has a name, it must be Indiana Jones.” Now, THAT’s a tagline.

“Temple of Doom” opens in Shanghai in 1935 at the Club Obi-Wan (writer/producer George Lucas was never known for his subtlety). Keeping with the Bond tradition of beginning at the end of an unspecified adventure (to say nothing of Ford’s white dinner jacket in this scene), the first act wastes no time in featuring a Busby Berkely-inspired song and dance number (in Mandarin!) a double-cross, a fiery impaling, a fistfight, a shootout, a fall out of a building, and a car chase, in rapid succession.

The plot proper begins when Indy crash-lands (via inflatable raft, long story), along with companions Willie Scott (Kate Capshaw, now better known as Mrs. Steven Spielberg) and Short Round (Jonathan Ke Quan, “The Goonies”) at a drought-stricken village in India. With their crops dead and their children abducted under mysterious circumstances, the villagers believe the trio to be saviors from on high. Despite being highly skeptical, Indy’s archeological sensibilities are intrigued by the village leaders’ assertion that their troubles are the result of a sacred stone having been stolen. Reluctantly, and with his companions in tow, Indy sets forth to recover the stolen artifact and discover the truth behind the mysterious disappearances.

As the first of (what would eventually be) three Indiana Jones sequels, 1984’s “Temple of Doom” had a lot to live up to from the onset. While many people may recall that “Raiders” was the highest-grossing movie of 1981, few realize how big a risk director Steven Spielberg and his best friend George Lucas took to create it. Indeed, “Raiders” was probably as close to a “make-or-break” project as Spielberg had ever received, with his career on the line following the box office failure of his overly-extravagant, star-studded, comedy flop, “1941” in 1979. Where Lucas was out to show there was more to him than “Star Wars,” Spielberg was determined to prove that he was still capable of delivering a hit film while keeping on schedule and under budget.

Conceived in 1977 while the duo was on vacation in Hawaii, “Indiana Jones” was to be to 1930s and 40s adventure serials what “Star Wars” had been to sci-fi movies from the same period. A lifelong fan of the “James Bond” series, Spielberg had recently been turned down by the producer of the 007 franchise (for being neither British, nor—at the time—prominent enough), and “Indiana Jones’” was pitched to him by Lucas (who had ostensibly retired from filmmaking following his heart attack while shooting “Star Wars”) as the perfect escapist alternative. With its irresistible mix of globetrotting adventure, old-school thrills, and an effortlessly charismatic, career-defining performance from star Harrison Ford (himself trying to transcend his own “Star Wars” shadow), all set to the now-iconic score by composer John Williams, “Raiders” was a hit in every sense of the word.

1984’s “Temple of Doom,” however, while being a financial success, has had a tendency to split critics right down the middle since opening day. Granted, a lot of the criticism leveled at the film is valid: graphic violence (along with “Gremlins,” this film led to the institution of the PG-13 rating in the US), casual racism, lack of a strong female character, and a flimsy plot are all in evidence. But none of the so-called “negatives” keep the film from being a shamelessly entertaining time at the movies. In fact, watching it now, one is struck by how much of this was accomplished as a direct result of the filmmakers’ desire to be as un-formulaic as possible in crafting it.

To wit, if “Raiders” was risky for introducing a state-of-the-art blockbuster with old-school sensibilities to modern audiences, “Temple of Doom” was equally dicey for going against the grain of what those same audiences now demanded to see from the good Dr. Jones. Nowhere to be found, for instance, are the Judeo-Christian influences and relative safety of featuring the Nazis as villains (it’s never politically incorrect to punch Nazis in the face) that characterized “Raiders.” In their place, we have the religion/threat combo of the Thuggee (etymological source of the word, “thug”) cult of assassins, reimagined as Khali-worshipping practitioners of black magic with a taste for human sacrifice.

The origins of the markedly darker tone have been attributed to George Lucas’ then-ongoing divorce and Spielberg’s own highly-publicized split with actress Amy Irving. Being the two most successful (and popular) filmmakers in the world at the time, the pair’s method of working out their frustrations was to produce a multi-million dollar motion picture wherein the hero is almost literally sent to the flaming pits of Hell with perhaps the most annoyingly-written (and performed) female lead in all of film history at his side.

While many films these days serve as mere clotheslines on which to hang a series of largely interchangeable action sequences, the final forty minutes of “Temple of Doom,” as directed by Spielberg (on the cusp of “auteur-hood”) and edited by frequent collaborator editor Michael Kahn (“Jurassic Park,” “Lincoln”), are a master class in increasing tension and escalation of stakes that, 30 years on, still manage to keep viewers on the edges of their seats.

Another factor that works in the film's favor is that it is, for all intents and purposes, a prequel, taking place in 1935—a full year before the setting of “Raiders.” With Indy being at an earlier point in his relic-hunting career, Lucas was able to avoid justifying how a man who (technically) witnessed the full power of the Ark of the Covenant in action could possibly scoff at the notion of a mystical rock with supernatural properties. In fact, it can be reasonably argued that the definitive character of Indiana Jones was forged by the events depicted here—when he retrieves the stone and tells Short Round that they’re not leaving the enslaved children behind, he sheds the “fortune and glory” aspect of his personality and truly becomes the hero we know and love.

All told, “Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom” is a thoroughly entertaining sequel that plays brilliantly (however chronologically roundabout) off the groundwork set forth by its predecessor. Boasting hard-hitting action, genuine thrills and imaginative spectacle (of a type no major studio head in their right mind would approve for production in this politically correct age), this film stands, 30 years on, not only as a snapshot of a bygone age of moviemaking by filmmakers at their youthful prime, but as one of the purest examples of a cinematic roller coaster ride you’re ever likely to experience. — VC, GMA News

Throwback Theater is an ongoing weekly column that will serve as a look back and an introduction to the box office blockbusters of years past, examining the films that helped inspire, inform and define subsequent decades of filmmaking and movie-going.