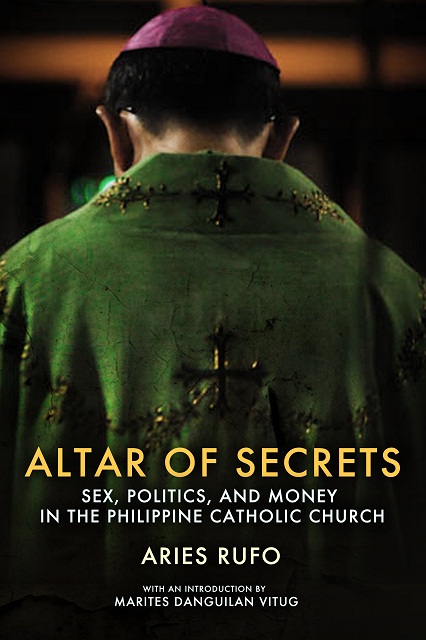

Book review: Unveiling sacred lies in 'Altar of Secrets'

This is for Filipino Catholics who can bear the painful truth. Bishops and priests who sired children, squandered money offerings, and jockeyed for power to get plum positions – you will find all of these and more ecclesiastical malpractices in “Altar of Secrets," a new book by veteran journalist Aries Rufo. While many of the sources were anonymous, the wealth of inside information gathered by Rufo through two decades of experience in covering the church beat has lent credence to his claim that some “princes” of the Catholic Church have lived immoral lives.

While many of the sources were anonymous, the wealth of inside information gathered by Rufo through two decades of experience in covering the church beat has lent credence to his claim that some “princes” of the Catholic Church have lived immoral lives.

In the introduction, Rufo takes pains to note that the book is not “divinely inspired” and that he believes the men of the cloth are also “made of clay.”

It is not about faith, or religion, or the Catholic Church as a whole. It is about the sexual misconduct of individuals who are preachers of morality. It is also about injustice, corruption, financial mismanagement, and the abuse of power by people who happen to be bishops and priests.

Rufo's purpose is to demystify the men in white vestments, who claim to be perched on moral high ground but are as human as the rest of us. Hypocritically, some people in the Catholic hierarchy in the Philippines demand transparency and morality in government and society while shrouding the wrongdoings of some of their men in utter secrecy, Rufo asserts.

Power play

Part I details the scandals involving some bishops who have betrayed their vow of celibacy. One chapter talks about an "orphanage" known to shelter the children sired by bishops and priests. Another follows the rise and fall of a young and brilliant bishop in the archdiocese of Manila, who was proven to have offspring. Then there's the story of a gay bishop who was accused of molesting young boys in a seminary.

The section ends with the revelation of a retired bishop that in the Philippines, 50 priests at any given time are in “conflict situations” – or have turned their backs on their vow of celibacy.

Part II revolves around the Philippine version of corruption and financial mismanagement in the Catholic church, which has its infamous counterpart in the Vatican.

There's a rich narrative on the Archdiocese of Manila's Monte de Piedad, a bank rendered bankrupt due to the lavish lifestyles and poor management skills of bishop-administrators.

Rufo also describes how millions of pesos in donations to charity were squandered by some bishops. In one diocese in Metro Manila, donations for disaster victims were never released for their intended purpose. An attempt by the faithful for a “transparency” dialogue, the author claims, was met with the bishop’s condescension.

The author likewise tackled the “mystery” of the millions in cash donations for the improvement of the church-run Radio Veritas, the communications outfit that played a big role in the 1986 People Power uprising that ousted the Ferdinand Marcos. The book hints that until now, no transparent accounting has been made to explain how the money was spent.

And then there's the jockeying for rich parishes in some dioceses among priests, who often compete for the coveted “intimacy in friendship” with the bishop to get plum assignments.

Part III discusses the intersection between church and politics in this country, starting with the scandal about the “Pajero bishops” who were close to the disgraced ex-president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo. The prelates are seen to have “collaborated critically” with the previous administration, which in turn showered them with favors ranging from expensive vehicles to large amounts of cash.

On an institutional level, the author discusses the Church's meddling in the affairs of the state, particularly its vehement opposition to reproductive health legislation.

To strike a balance, the author did cite some honest attempts at respecting church-state boundaries, as seen in the partnerships on governance initiated by the late Interior Secretary Jesse Robredo. Much earlier, there were also attempts in getting local parishes involved in the fight against corruption, initiated by former Ombudsman Simeon Marcelo.

The last section, Part IV, is devoted to what Rufo considers the “failed promise” of renewal for the Church through the Second Plenary Council of the Philippines (PCP II). He said the spark initiated by Vatican II had inspired the church to try to transform itself and pursue a preferential option for the poor. But the Basic Christian Communities that blossomed during the Marcos dictatorship seem to have faltered as a new way of being the Church in the Philippines, the author contends.

A little bit of context

The book seems to hold certain assumptions that do not fit into the Church hierarchy's understanding of itself, thus depriving the reader of a larger context in which to appreciate the cases presented.

For instance, on financial transparency, there seems to be an assumption that the Church is a public trust similar to the government, which gets a share of the income of wage earners. It overlooks the fact that the Church is a private institution. This was the point of Jaime Cardinal Sin's response when a reporter asked him, “How wealthy is the Church?” The Cardinal retorted: "Have you made your contribution to the Church?" When the reporter said, "No," the Cardinal said, "Then you have no right to ask that question."

There is also no distinction made between diocesan priests, who have no vow of poverty, and religious priests or those who belong to congregations, who do. It is certainly no excuse, but one reason some diocesan priests are tempted to embezzle church money is because they need to save for their retirement. They are not like the Jesuits, Franciscans, Dominicans, Augustinians or other members of religious congregations that take care of the needs of their members when they grow old and thus, have no need to have money of their own.

And then there's the oft-debated separation of church and state: Archbishop Emeritus Oscar Cruz has justified their involvement in political and social issues by saying, "the separation is understood in the sense that the state will not adopt a state religion."

The late Jesuit Bishop Francisco Claver, who once headed the social action commission of the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines, has clarified this matter thus: The Church should not meddle in partisan politics or the “small p” but it should be immersed in the “big P” or the polis – the general life in the city.

In an attempt to present a basis for his idea of separation – meaning dichotomy of roles – between the supposedly “heavenly” Church and secular authority, Rufo cites anonymous scholars and invokes the famous passage attributed to Jesus: Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and unto God the things that are God’s.

“But what belongs to Caesar that doesn’t belong to God after all?” Fr. Kees Swinkels of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart once said, a typical reaction among socially active church people that differs starkly from the layman Rufo's interpretation of the same passage.

Rufo is absolutely right in his cry for change and renewal of the Philippine Catholic Church, to become truly a church of the poor. But the book could have provided a more balanced view of the Church by going beyond the RH law and also looking at other issues that progressive priests and bishops have advocated on the sidelines less loudly, such as environmental protection and indigenous peoples' rights.

The seeds of renewal have already been sown in various documents of the Second Vatican Council, especially Gaudium et Spes, which opens with these words: "The joys and the hopes, the grief and the anxieties of the people… especially the poor… are the joys and hopes, the grief and anxieties of the followers of Christ.”

Amid the scandals in the church detailed in the book, Filipino Catholics would do well to remind their religious leaders about the vision of Vatican II: the Church as a community of the people of God striving to work towards justice and peace. – YA/HS, GMA News