ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

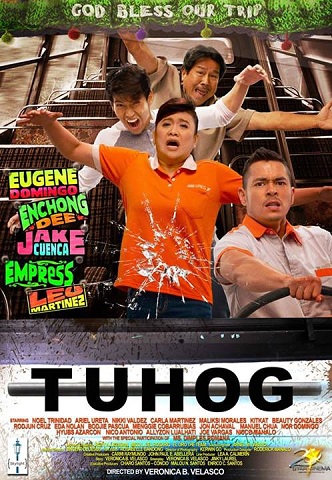

Movie review: The greatness of 'Tuhog'

By KATRINA STUART SANTIAGO

What you do not know when you enter the cinema to watch this film is how tiring it will be. And I mean that in a good way, in the way that a film should be able to invite you into its world, and take you on a ride, giving you no choice but to live with it.

What you do not know when you enter the cinema to watch this film is how tiring it will be. And I mean that in a good way, in the way that a film should be able to invite you into its world, and take you on a ride, giving you no choice but to live with it.Because you will be taken by this story, you will become part of it, not because it gives you life on a silver platter, or offers you a world where things are beautiful. Instead, you become part of it because it is painfully real. And no I don’t mean that it is in the mode of realism, I mean that it is as real as the lives we live, as normal as we know life to be.

The greatness of “Tuhog” is its creation of this community within the film. But also it is about its ability to include the spectator in that community, to engage the viewer so much that she might forget to disengage with the world of this film.

This film takes you on a ride, yes. And no, it’s not some fantasy-filled, falsely created world that it gives you. In fact it barely gives you anything grand, or spectacular. But it sure gives you exactly what you need, and does exactly what we’ve always known cinema to do, but which we rarely see anymore in our films.

All you need to be, is open to its possibilities. All you need to do, is to be there.

Three disparate lives

The story begins and ends with the crisis of three bus passengers pierced by one steel pipe, now in the hospital, their injuries being assessed by the team of doctors and interns. An accident brings them together in this way; they are nothing but strangers to each other, even as the people we encounter every day allow for a level for familiarity. They do not know each other by name.

They also have nothing in common but that bus, where one Fiesta (Eugene Domingo) is the konduktora, and recently retired family man Tonio (Leo Martinez) and college student Caloy (Enchong Dee) are regular passengers. The disparity among their stories is the point.

Tonio’s recent retirement has almost pushed him over the edge, at the same time that it keeps him as creature of habit: wanting the old chair he’s always sat on, his body waking up as early as it would for a day in the office. He is old, but has fun with a group of friends who are like him, spending their days playing Pusoy Dos and encouraging him to go for his dream of becoming panadero.

That is, spending his retirement money on opening a bakery, and making the pandesal himself. His children are aghast, and question his ability to keep business. His wife (Carla Martinez) cannot but be supportive despite her apprehensions. That this story works of course is also due to Martinez as Tonio, where he is perfectly unhappy and discontent in the beginning, and eases into a man who has a spring in his step, an excitement about him. That moment when his wife visits his bakery about to open to show her support, and Tonio throws out a tear or two: saying he doesn’t know if he’s being right, or being stupid about this.

You will cry. Because you want this man to succeed, and you know he is scared and uncertain, but he deserves it as much as the next man or manong in your life, your father included.

Fiesta's tough exterior hides the story of the violence of abandonment and alcoholism that she grew up with, that she continues to live with. Her reputation precedes her, and Nato Timbangkaya (Jake Cuenca), new driver for her bus, is forewarned. But Nato doesn’t know to quit. He breaks through to her, and soon enough gets her pregnant. They do not talk about this pregnancy, as Nato’s story quickly unravels on that bus, and Fiesta does the decent thing, she does what is right as she is wont to do.

Domingo is at her best here, where she doesn’t fall back at all on any fictional and public persona we know her to have, and where she is allowed to take a character and run with it. Which is to say her Fiesta is a great display of containment and control, the stability in her feet and the weight in her step that’s expected of someone who stands on a moving bus all day, becoming but part of the person that Domingo creates for Fiesta: dependable and rational, if not painfully so, no matter the heart.

That Cuenca is even able to survive this story with Domingo is a measure of the former’s acting, which was surprisingly believable despite the pretty boy good looks.

The realness of hormones and young love, meanwhile, is what’s at the core of Caloy’s story, whose long-distance relationship with Angel (Empress Schuck) is taking a toll on his, uh, libog. The promise of doing it for the first time with each other keeps Caloy going, but the motley crew of two friends who are just as hormonal as he is, and female classmates who are so willing to get in bed with him, makes self-control difficult. The unraveling of course is about a betrayal, Angel’s and his.

Dee’s Caloy is your every Pinoy college boy, taken over by body and desire; he and his barkada do hormones and juvenile Pinoy macho better than we’ve seen it in film or television in years. Which is to say, this is as real as it used to be in those films with the Guwapings, from “Pare Ko” to “Mangarap Ka.” Thank heavens, Dee has the chops for it.

An imagined community

These disparate stories obviously have nothing in common, yet each one will hold you by the hand – if not by the neck – because these are lives that are familiar and as real as they come. There is no insistence here that we piece together these stories, that we force it to mean something bigger than its disparity. In fact there is nothing here but a bus that ties them together, that stretch of road that takes Tonio from where he lives to what he calls the bayan, and Caloy from the bus station (to pick up Angel) to his boarding house. There is nothing but the bus and Fiesta, from one point of that road to another, back and forth, back and forth, every day.

Yet there is no redundancy in this film at all, and one doesn’t feel like they’re being taken for a ride and nothing else. Instead what we are given is a sense of community, a sense of what it is, what it means, to be taking that bus every day, to be mere creature of habit, to be part of the wheels that turn, day in and day out. It is not redundancy, as it is repetition. It is not mere repetition as it is the small things that change in us, even when these remain invisible.

And this is how these stories engage you as spectator; it is how it draws you in. Beyond what is visible as the living breathing characters of this film, it is the emotional turmoil, the personal struggles, which you cannot but understand. You are taken by these stories because each one reveals a very clear notion of love and loss, of becoming and undoing, of crisis and simple joys. These are different across all these three characters, of course, but all of them speak of such human impulses for loving and passion, for want and desire, that you can’t but know Tonio and Fiesta, Caloy and Nato. You can’t but engage, sympathize, feel for what they go through, and who they are.

Here, “Tuhog” successfully does what very few commercial films, and what too many artsy-fartsy or poverty porn indie films, have completely failed at doing: create a world within a film and create a community out of its viewers. Here there is no distance between you and the world that the bus traverses. There is no you being taken in merely by the fantasy or fiction of cinema. Here, you are also the daughter of Tonio who questions him, the son who doesn’t care enough, as you are Tonio who wishes to finally fulfill a dream. You are Fiesta who doesn’t know of love, you are her drunkard father (Noel Trinidad) who doesn’t know to quit. You are as young and as restless, and as unsupervised and free, as Caloy and Angel.

But also you are merely another bus passenger, the one who didn’t get pierced by the same tube, and whose story remains unknown, untold by this movie. You are but a stranger in that bus filled with so many others like you who brave the daily commute, who bravely live every day in the throes of nation. And when I say throes, I do not mean poverty, which isn’t even here really. As I the daily struggle to live, to survive, through the past that we hold dear, the future we cannot even begin to think of.

Because in the present, “Tuhog” tells us, there is just this: the routine that makes up the daily grind, a highway we live off, a moving bus filled with strangers, you and me in the same space of nation.

And always, the possibility of dying.

Death becomes us

That these threes stories, that this movie, are bound by a bus speaks to us even more. That is, if we have all experienced being on a speeding bus, or train, or jeep, cruising on a highway that is by all counts dangerous. The one thing I kept waiting for was a map of this world that the movie was moving in, where that bus was obviously on EDSA, bound for Fairview and back, but it was unclear what Tonio mean about being dropped off at the bayan, or where exactly that bus terminal was that would be the setting for Fiesta and Nato’s love story.

Then again, maybe that was the point. Sometimes all you need of a map is a moving bus, that isn’t really going anywhere. Sometimes all it takes is the sense to concede to life and what it gives you, if not to rebel against all expectations and do what you actually want. Sometimes it is the small things like love and its possibilities, like learning to bake bread, or finding a wife who will understand, that make our days worth it. Sometimes, it is nothing but a string of heartaches, if not a future that is far from being bright and happy.

At the heart of “Tuhog” is the sense that all of these matter because we live. None of these matter because we could, in fact, die tomorrow.

And the question is not so much who deserves to die as it is who is ready for death, because she has had enough of living.

Those of us who live, of course, are left with nothing but today. — BM, GMA News

“Tuhog” has a screenplay by Veronica B. Velasco and Jinky Laurel, and story and direction by Veronica B. Velasco. It is produced by Skylight Films.

Katrina Stuart Santiago writes the essay in its various permutations, from pop culture criticism to art reviews, scholarly papers to creative non-fiction, all always and necessarily bound by Third World Philippines, its tragedies and successes, even more so its silences. She blogs at http://www.radikalchick.com. The views expressed in this article are solely her own.

More Videos

Most Popular