Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Bart Guingona: Theater centaur explores the unknown

By SYLVIA L. MAYUGA

A question hung in the air as stage lights dimmed on “Red”’s last Manila performance: What in the name of the theater gods led to this brilliant moment? For 90 unrelenting minutes of impeccable performance, two actors explored painter Mark Rothko's mortal struggle with his foes—moneybags reducing his art to decorative trophy, an art world drifting from abstract expressionism to irreverent pop art, and last but not least, himself. This artist reverent about his art, beholden to his eyes, was too blind to see: he was his own worst enemy.

Playwright John Logan’s deepsea dive into this tortured Jewish psyche opened in London to mixed reviews in 2009. Despite its Tony Award a year later, its Broadway run was limited. Hard fact: for all its brilliance, “Red” is not “entertainment” to Hollywood- and Broadway-soaked audiences. Its mounting in the ever noble, ever loyal, ever trivia-prone city spoke of daring, confidence and vision.

What was one to do but trace it back to the culprit, Bart Guingona? Choosing “Red” for Filipino audiences, playing its lead role, simultaneously directing his handpicked supporting actor, Joaquin Valdes, was a tough act that exacted a personal toll.

“How do you feel after an evening of 'Red'?” I asked the morning after. “It's a roller coaster,” he confessed. “I reach for the alcohol, I laugh, I'm giddy. Then I cry. Ha! Like the contrast of the red and the black.”

Red was life, black was death in Rothko’s eye, he said, and his canvases were slowly moving from blue to black before his suicide. Playing Rothko was giving him insomnia.

“Plays like this are intimations of mortality. This self-destructive role opens a door to the darkness inside me,” Bart confided. Then he smiled, “You know? I’ve discovered the Black Hole is a nice place to be.”

That led back to the memory of his own early intimations of mortality. At 14, after what should have been a routine appendectomy, he was rushed back to the hospital in excruciating pain. His family suspected accidental perforation of his appendix in his operation, infecting the cavity enclosing his digestive organs. He remembers well how sharp his senses were—wrapped in ice to bring his burning fever down, feeling people dying around him as he hovered between life and death.

Drifting off to sleep in the ICU, he had a “dream” of being inside an Egyptian pyramid with hieroglyphs dancing around him. Past life memory in near death? Who knows. What he’s sure of is how he “grew up fast.” Today, 34 years later, Bart Guingona is one bright thread in Philippine theater history.

Siren call

This middle child of the late businessman Benjamin Guingona (youngest brother of former senator Teofisto Guingona) went to the well-heeled Colegio de San Agustin from grade school to high school. He loved football and tried out theater, but not till college at the UP would he see: theater was his calling.

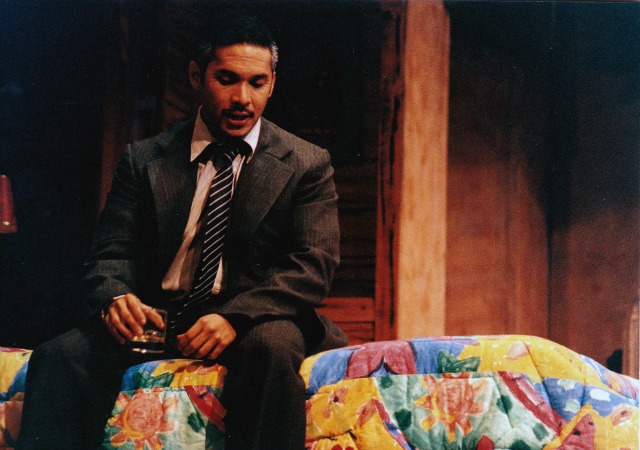

In 'George, Same Time, Next Year' (1997). All photos courtesy of Bart Guingona

Theater genius Anton Juan was brooding over “Marat Sade” just then. This Peter Weiss play-within-a-play set in an insane asylum, with the blood and madness of the French Revolution, first staged in a UP burning with revolutionary fever, met an untimely end soon after Martial Law. Remounting the play a decade later, Anton asked newbie Bart to play the asylum director. How did that feel? “Scary,” he said.

And so, baptism of fire began a double life for Bart, an “anomaly in a family of pragmatists”—economics course on one hand, theater’s siren call on the other. Embracing a passion few can live on, he learned to balance his right- and left-brain early. More roles came in Wilfrido Ma. Guerrero’s UP Mobile Theater, UP Bodabil’s street theater and Antonio Luna in Noriega’s prizewinning “Juan Luna.”

With few jobs to be had in a tanking economy after graduation in 1983, the double life continued—a day job as financial analyst in the Ministry of Human Settlements, after-hours with his true love. Instinctively moving from “heavy” UP roles, he joined Repertory Philippines (Rep), hoping to broaden his experience.

As seething discontent with dictatorship waited to pour into the streets, Rep director Zenaida “Bibot” Amador was training the likes of Lea Salonga, Monique Wilson, Pinky Amador, Menchu Lauchengco-Yulo—and Bart—in Broadway-style theater. When all hell broke loose with the Aquino assasination, Bibot discovered that Bart could “sing instinctively,” thanks to his musical father’s genes.

So young Bart played the singing bookseller Avram in “Fiddler on the Roof”; his first lead role in the musical “You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown,” and supporting roles in the musical comedies, “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum” and “Woman of the Year”.

“Escapist! Burgis!” leftists staging passion plays on the rally front sneered at Rep. They had forgotten that Bart Guingona, a member of the Youth for Nationalism and Democracy in UP, was a “very good friend” of their icon, Lean Alejandro. No, rabid leftists were not about to see Rep as an informal theater school playing its part in the larger human drama.

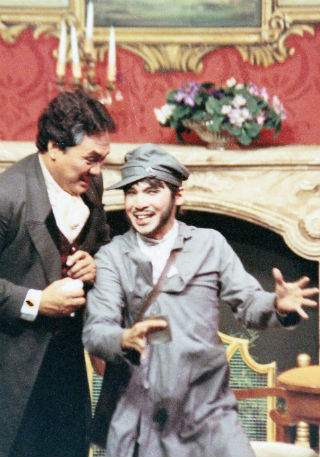

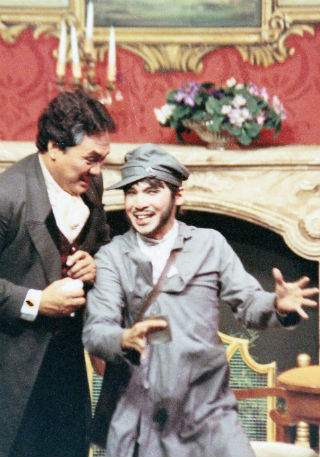

In 'The Government Inspector' (1985)

Bart grew in a dizzying variety of supporting roles along with the Parliament of the Streets—the musical son of an aging Appalachian widow in “Foxfire”; the postmaster in Gogol’s comedy of errors “The Government Inspector”; a black sheep in the mystery comedy “Whodunit”; Deputy Fred in the “Best Little Whorehouse in Texas”; the Manager/Emcee in “Piaf”; the penny-pinching Jethro Crouch in the updated Viennese Renaissance comedy “Sly Fox”; the black musical legend Fats Waller in “Ain't Misbehavin”; composer Vernon Gersch in the romantic comedy “They're Playing Our Song”; tenor Tito Morelli in the comedy “Lend Me a Tenor”; and the Bandit King in the musical “Kismet”.

Is all that why we never saw him at rallies? Or was he shunning its extremists? Not quite. “We never saw the musicals in any kind of ideological light. They were just part of a job in a business that demanded, ‘the show must go on,'” he said. “In Truffaut's ‘The Last Metro,’ a theater group kept performing even in the midst of war. We saw something noble about keeping spirits up in times of crisis.”

In fact, Rep would interrupt rehearsals to rain yellow confetti on the marching crowd from the 12th floor of the Insular Life Building in Makati. And “in the critical days of EDSA, we would all remove our makeup, pack into someone's Ford Fiera, and join the crowds in Aguinaldo.”

On with the show, then, after EDSA, playing lead roles in Manglapus’s musical, “Yankee Panky”; an eccentric fop in Agatha’s Cristie murder mystery “The Mousetrap”; a husband caught in the sexual revolution in “I Love My Wife”; a flummoxed detective in the comedy “Busybody”; Prince John, one of the four quarreling sons of Prince Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitane in the royal family drama, “The Lion in Winter”; Robert Kent in the drawing room comedy, “Aren’t We All?”; Neil Simon’s army buddy Epstein in the semi-autobiographical “Biloxi Blues” and so on.

“There was nothing I could or would not do when I was young,” he said. “There was a season in Rep when I played a passionate seminarian, a five-year-old boy, a 98-year-old artist, a yuppie, a German scientist, a Chinese waiter, a sterile jock—in quick succession. It was just the way it was.”

An emotional athlete was emerging. “When I was doing the reckless genius, Nicanor Abelardo in 'Bituing Marikit,' I was also doing the Director in ‘Death in the Form of a Rose.’ Both roles required me to die dramatically in the end. If I were less wide-eyed and optimistic then, I would probably have sunk into deep depression. But acting is wonderful; it allows you your catharsis onstage; you need not take it anywhere else in your life.”

In 'Rizal, Mga Teksto at Komentaryo' (1996)

So what were his most memorable lead roles in the 150 plays he’s been in? Besides Nicanor Abelardo and the provocative Italian poet/ journalist/ filmmaker, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Bart ticks off Hamlet, John Proctor in “The Crucible”, Rizal in “Mga Teksto at Komentaryo: Ang Paglilitis at Pagkamatay ni Jose Rizal” by Dumol, and, of course, “so far the most complex”, Mark Rothko. Someday he’d like to play Richard III, Lear, and Johnny Byron in Jez Butterworth's “Jerusalem,” each one a different challenge.

After four short years, Bart was “theater master” of Rep’s stage workshop and instructor for the CCP’s fledgling Tanghalang Pilipino’s acting workshop. His ALIW Award for best stage actor in 2003 recognized his passion, talent, discipline and range. Did he mind playing more supporting roles than lead? No, it was all about exploring character: “I thank Zenaida Amador for not seeing me as leading man material,” he said. “I ended up filling all the ‘un-castable’ character roles that stretched me as an artist.”

After two theater grants in London, the open mind that slid with ease between the antipodes of Rep and UP was acting and/or directing for most of Manila’s major theater companies—“The Crucible” and that hilarious all male “Taming of the Shrew” for Rep, “The Maids” with PETA, “Blood Wedding” for Dramatis Personae, “Ang Kuripot” by Tanghalang Pilipino, and “Julius Caesar” for Gantimpala Foundation.

Bart Guingona has grown into a centaur—half-man, half-horse—seeing far as he gallops through ever wider, deeper ground. 'Seeking fame is not my style'

When I first met Bart Guingona at a press conference on the questionable National Artists Awards in 2009, he never let on that he was part of the protest's organizing core. His reason revealed the inner man: “I always prefer to work in the background, more satisfied to see results than hog the credit. Seeking fame is not my style. Recognition should be a byproduct, not an end.”

In 'Hamlet, Hamlet' (1994)

This path unfolds in valiant Philippine theater history. Back in the original protest theater, babaylanes risked their lives in shamanic calls for their people to resist white conquest of their soil and soul. Then came Marcelo del Pilar’s theatrical satires on frailes in the wicked “Dasalan at Toksohan.” And who can forget the mischievous barbs of protest in Tondo’s brave teatros under the Americans and the veiled protest humor in zarzuelas under the Japanese?

In postwar reconstruction, tiny groups of theater faithful, like Montano’s Arena Theater and the Manila Theater Guild, held their ground for drama. In the '60s, little PETA born in the ashes of Fort Santiago with Bayaning Huwad grew into a thriving institution raising a clenched fist at dictatorship. The communist temptation that came with the passion for change was only one of the many our people have lived through theater.

Actors' Actors Inc.

By the early '90s, some Rep stalwarts were “dissatisfied with the material we kept doing.” Jaime del Mundo dreamt of classics and opera; Menchu Lauchengco-Yulo yearned for cutting-edge musicals. Bart was disturbed by “the lack of complexity to much of the old work.” So they co-founded Actors’ Actors’ Inc (AAI) “to do work that needed doing but deemed impossible to produce.” Bibot’s babies had outgrown their Broadway mono-diet.

AAI’s first season in 1992 was a triad of old and new—Shakespeare's “Macbeth,” dark drama in “Kiss of the Spiderwoman” and a new take on “Peter Pan.” In 1998, it announced its long-range vision for “idea-driven, provocative, cutting edge and brave plays... a challenge to the accepted notion that entertainment should be escapist and shallow” in The Necessary Theater (TNT) Series.

As the world approached the Third Millennium, its plays bore the marks of “interesting times” on their brow:

“The Atheist,” a satire with a cynical American news reporter clawing his way up the journalistic ladder from trash to sordid celebrity. (Sound familiar, Manila media?)

“Via Dolorosa,” a disturbing theater monologue on the fratricidal Israeli-Palestinian conflict keeping the whole world hostage. It rails against the “political-philosophical-religious diehards, Israeli and Palestinian alike, who seek religious justification for excessive behavior on either side.” (Sound familiar, fundamentalists, commies and anti-commies?)

“Mother Tongue” by Paul Stephen Lim, an ex-Chronicle newspaperman and now Chinese-American professor. This play tells the story of “David Lee and his mother Lilian, a 14-year-old child-bride who left her parents in China to marry an older man in the Philippines in the late ‘30s.” Forty years later, David takes the same sort of journey, this time, through “the nature of language itself, what we lose and/or gain when we give up one language for another; how our thought processes, and maybe even our values, are determined by the language(s) we speak and write, perhaps even dream in.” (Sound familiar, Fil Ams and OFWs?)

“Shopping and Fucking” is a “barbarous, shocking morality tale of our amoral times, a unique stage portrait of a lost generation of dehumanized youth rotted by social and economic abuse,” as one blogsite describes it. (Sound familiar, shabu addicts, child prostitutes?)

Not forgetting romantic love, AAI raised it to a mythic level in “Once on This Island,” a musical about Tio Moune, a dark-skinned peasant girl and her impossible love for a grande homme of Haiti’s white ruling class. With the gods of earth, water, love and death, Tie Moune rises above her love as she conquers self, time and place, even death.

Then there was the smash hit musical “Children’s Letters to God” in 2008. Art critic Gibbs Cadiz said it best: “ ‘God’ rinsed of the contemporary default positions of irony, attitude and quotation marks can carry its own self-destructive gene: How far before it capsizes into mush? Impressively, ‘Children’s Letters to God’ held on to great poise and the steadiest of care. Guingona and Lauchengco -Yulo’s sterling work with their young actors birthed a musical of pure, uncomplicated sentiment, all of it honestly earned. It must be seen to be believed.”

Idea Theater and beyond

Bart Guingona, artist centaur, knows his ground onstage and off. He revealed the right-brain, left-brain balance required by “Red”: “When we began, my economics background helped me block the play with system. But after a while, Joaquin complained that he was ‘acting alone.'” So the director switched to actor mode and said, “Okay. Let’s act together now’.”

In 'Tuesdays With Morrie (2009)

But why don’t we see more of his kind of theater? “There’s a reason our plays are so sporadic,” he said. “We're competing in a marketplace of lazy entertainment. We have a small loyal following, just about enough to cover costs for individual productions. We've received government subsidies in the past, but the drawback is the bureaucratic ribbons we need to navigate to get the funding.”

AAI also has several theater-loving sponsors. Do they ever threaten artistic freedom? “Sponsors first need to support our vision. They don't give very much but I'm convinced we will see the day when more people will be on our side. Like all things novel, it requires a measure of convincing and ‘audience-building’, of marketing and building demand for something in short supply: intelligent entertainment.

“I dream of making theater a mainstream pursuit and entertainment choice for—especially—decision-making adults. I want that audience that paid P10,000 per ticket to see ‘Phantom of the Opera’ and give them an equivalent value for a fraction of the price,” said this rare artist/economist.

Offstage, Bart works in different media for love and life. As writer/ director, he’s done some hot stuff, like the multi-media celebration “Rendezvous avec les Sense,” “Fire Water Woman” with Ballet Philippines and Musical Theater Philippines, and Philippine pavilion performances in the Shanghai world expo 2010.

His overhead is met by doing roles in TV sitcoms, movies, commercials and voicing assignments; presentations for some of the largest corporations in the country and events like the APEC conferences in Hong Kong and Davos. But there, too, is the less lucrative, more rewarding psychic income from directing the CCP Centennial Awards, the Centennial Celebration Flag Ceremony in Kawit, Iloilo and Butuan, riotous Gridiron Nights at the National Press Club, and the lectures he gives on theater in and out of Manila.

Seeing things whole, this activist centaur also chairs the NGO pagbabago@pilipinas, co-founded with fellow-visionaries like the recently departed sage, Mario Taguiwalo. Bart is also the moving force of one of its most significant projects, Media Nation, staring down the present reign of media for sale.

“Neck deep in advocacies as necessary as theater,” this Filipino has never even been tempted to pursue his passion for theater abroad. “My place is here,” he said quietly.

From an earlier time of great ferment in our richly gifted, yet woefully unequal nation, the older theater visionary Anton Juan echoes: “In the Philippines, where the extremes of pain are so real, we really had a vision, and this group of then-young actors and directors made a mark...”

Vision continues. As our country spins ever faster on winds of change, the centaur sees a future landscape: more venues, brilliant playwrights, polished artists, a thinking audience inspired and enlightened by their own true story... Indeed, when did things ever really change without a dream?

This is one fierce Charlie Brown. —HS/KG, GMA News

More Videos

Most Popular