Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

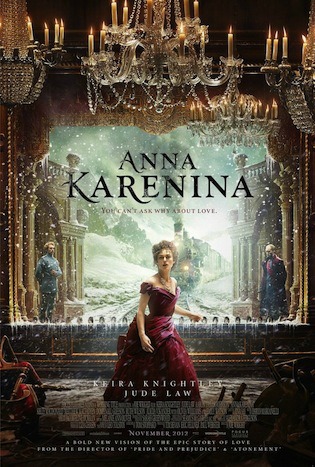

Movie review: The crazy in 'Anna Karenina'

By KATRINA STUART SANTIAGO

I have a love-hate relationship with “Anna Karenina.”

Yes in quotes, because it’s the film I speak of, not the person Anna. The truth is one of the things this Joe Wright version does is pull you toward the two extremes of either loving it or hating it. I have fluctuated between both in the stretch of time that I’ve sat on this review.

Because Anna (Keira Knightley) is crazy here, moving about without much motivation, and really only being dictated on by desire. But she barely speaks, and doesn’t quite articulate what she wants. Great moments of urgency or distress—say, Vronsky (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) falling off a horse, or the desire to see her son—become the prerequisite for words. Her silence would also be fine were it the one silence in the film; but Anna’s husband Karenin’s (Jude Law) ability at suffering through the pain and shame of infidelity, with grace and seeming pride, despite the silence, just outshines the lead character’s lack of words.

Too, there is this: Anna’s silence barely makes sense in the context of this film, which by all counts, is noisy.

This crazed staging

And I mean in a frenzy, where people’s movements are what’s given utmost importance, playing around with scenes on fast forward, if not in slow motion, and those that freeze in a moment. This added to the craziness that was in Anna too, as you tend to remember her in scenes and not in terms of grand moments of grace and depth. So you remember her on the train, moving back and forth, back and forth. You remember her dancing. You remember her getting dressed. You remember her in bed with Vronsky. You remember her head on those train tracks.

Everything else about her character is lost in this staging, and one doesn’t even need to remember that in the original novel Anna is described to seem like a real-bodied woman (as we’d like to call it in the present). To me this was always a crucial description if only because it spoke to me about an Anna that had a weight in her step, a confidence too, versus this version that was waif-like and weak.

Which is also my issue with this Anna’s craziness: it is tied to a weak persona, rendering the later suicide to be about precisely that, too. It goes without saying that this would be a portrayal that does no justice to the original Tolstoy woman. It has to be said too, that there was much reason to hope that this kind of Anna could be imagined without making her seem like a weakling.

Some power in the crazy, maybe?

Craziness after all can be about having a sense of self in the context of society’s impositions of propriety and decency, if not given this particular kind of patriarchy that dictates upon the women in this story, rendering the women seemingly unable to take charge of their lives. It is from the latter in fact that Anna’s craziness could be portrayed with a little more rationality, an amount of logic, possibly allowing for her character’s craziness more depth.

Because that is possible, isn’t it? So that at the very least, how this woman’s life ends doesn’t seem inevitable and expected, and it could be layered with the oppressiveness of those times. The latter is what’s missing in this movie, though there are scenes that actually work with it, dialogue that mentions it. But there is nary a sense of how this can feel claustrophobic for someone like Anna, or how her craziness could be a real conscious version of rebellion.

As it is, it seemed like Anna was merely being carried away by the rest of this film, in this frenzy of sets shifting before our eyes, a bed on a stage, gardens within structures, sunlight shining brightly on a bed. And while it’s easy to find this device discomfiting, it is also what breathes life into this version of “Anna Karenina.”

This world’s a stage

Which is to say that while it was disconcerting in the beginning, what became the one charming thing, the one unique thing, about this film’s telling of the Tolstoy original is its use of devices that one would know to be of the theatrical stage. And this is not just the shifts in setting, with doors opening to the next space, or the stagehands literally carrying a backdrop behind the characters; it was also in that first scene where Anna is getting dressed—that is, she is being dressed by servants, as if a doll, as if an actress getting dressed for a scene. It would literally too, be the fact that Anna’s son’s room is up on stage, that below it is a field of green green grass.

It is ironic of course that it would be these theatrical devices, transient as they all were, that would ultimately allow for a sense of order in this film, establishing logic for these characters’ unraveling. Without the conventional shifts from one backdrop to another, and with nary a need for characters to explain where they were going (or even where they were at), what one is left with is a sense of how the people here might be secondary to the movement of time, the changes in space.

To some extent, it is only this device that allows for Anna’s craziness to make sense. It reveals her as someone carried away by moments, swept up in desire and possibility, trapped in society’s judgments, escaping patriarchy’s inability to understand her. She is not so much reacting to her context as she is merely within it, flowing with it, reveling in whatever it gives her, languishing in an ability to disregard public opinion, breaking down at some point when the pressure is too much.

Yet given the theater within which her life happens, given the stage on which she seemed to have been living, all that we get out of Anna and the other characters here is the sense that they are mere performers in a story already written. There is no motivation needed as such, no rationale behind their actions. All it needs is the story that works.

It seems that this could also only be a statement on the movie versions of books. It seems that in the end the value of “Anna Karenina” is in its daring to do this telling. Its failure is also in precisely that, too. —KG, GMA News

Katrina Stuart Santiago writes the essay in its various permutations, from pop culture criticism to art reviews, scholarly papers to creative non-fiction, all always and necessarily bound by Third World Philippines, its tragedies and successes, even more so its silences. She blogs at http://www.radikalchick.com. The views expressed in this article are solely her own.

More Videos

Most Popular