ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

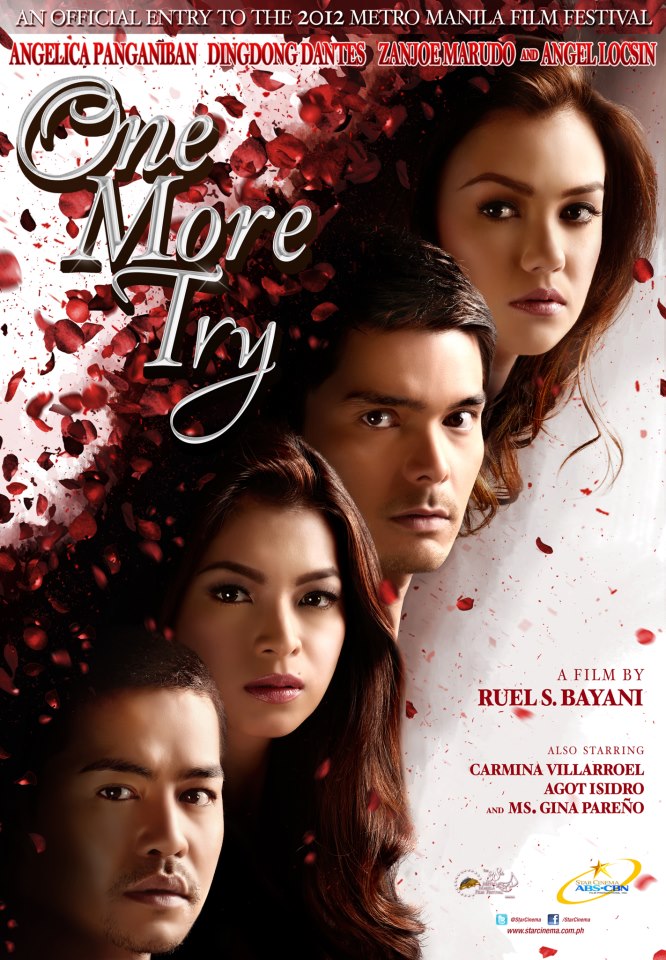

Movie Review: One question for `One More Try'

By Katrina Stuart Santiago

Which one of this movie’s main characters screams at some point, hysterical in place of distraught: bakit hindi natin dalhin ang bata sa States?

The answer was simple enough: there’s not enough time to save this boy’s life, the one who is at the center of this movie, the reason for its crisis. He needs a bone marrow transplant for a rare condition that will kill him.

The difficulty is in finding a match to his bone marrow; the other difficulty is the fact that he is borne of a one night stand. He doesn’t know who his father is.

It is clear why “One More Try” (directed by Ruel S. Bayani, written by Jay Fernando and Anna Karenina Ramos) revolves around Bochok (Miguel Vergara), the little boy who lives with his single mother Grace (Angel Locsin) in Baguio; it is quickly established though that at its core, this story is about the two relationships that will ultimately be rendered irrelevant by the need to save the boy’s life.

Directed by Ruel S. Bayani, written by Jay Fernando and Anna Karenina Ramos

The story begins swiftly, establishing two distinct but ideal relationships between Grace and current boyfriend Tristan (Zanjoe Marudo), all the way in distant Baguio; and Edward (Dingdong Dantes) and Jacq (Angelica Panganiban), in Manila. The latter are married, and living the dream lives of professionals with the fancy house, nice cars, and designer clothes.

The two couples begin their days with a playfulness borne of long relationships, the familiarity already at the point of keeping each others’ diets in check, the possibility of the woman quitting her job to be wife AND mistress (her own words) already in the horizon. The desire for a child is the unsaid in the huge but empty home; it is articulated when Jacq gets her period.

Grace and Edward, in situ

Meanwhile Grace bids Bochok and her mother goodbye, with a sense of urgency about her task for the day, which involves taking the bus to Manila even as Tristan offers to drive her. It is telling of the kind of single motherhood she has survived for five years, informed by an independent streak and a strong will.

That the status quo for both these relationships were established in the first 20 minutes or so of the film, the difference made as stark as possible, is a wonderful thing given recent local drama which tends to develop status quo as it goes along. Establishing the need for the Grace and Edward meet-up five years after their uh, one night only engagement is done just as quickly.

We got a kid, he’s sick. You need to get your bone marrow tested.

Now the standard response to the fact of infidelity as handled in local drama, is secrecy. But Edward surprises by bringing Grace to dinner with Jacq, for what he says is “a situation.” And then the movie unfurls, where Edward is no bone marrow match, and they are told in no uncertain terms that the only hope for Bochok is a spanking new sibling. It’s in vitro fertilization of course that is the first option here–where Jacq expectedly articulates that money is no object, which also allows her to imagine that it is all that they need to cure the boy.

But in vitro doesn’t work, and Bochok’s need for a transplant is suddenly an urgent one, something that only sinks in when Jacq confronts the fact that the only other way to save the boy is if she allows her husband to have sex with Grace. And it is in the midst of her major confrontation scene with Edward that Jacq screams hysterically about other options, i.e., bringing the kid to the States maybe? It not just points to the most basic information that an audience must demand of a movie like this: a timetable.

When we say someone is dying, we give them a number of days, a month? Two? A year? And in the case of “One More Try” where pregnancy is the option, then you’re counting at least nine months, plus the months that they are just waiting to get pregnant, and the months after a baby’s birth before he or she might become a bone marrow donor (research reveals about a year to 14 months after a baby’s born).

That’s at least two years or so, of Bochok being sick, and in urgent need of a transplant. That’s at least two years, during which certainly going to the US could be option? Finding donors a possibility?

And while we’re on the subject of making this believable as a drama that revolves around a sick child, neither Jacq nor Edward ask to see another doctor for a second opinion on Bochok’s ailment. Which is this movie’s major loophole too, given the preposterous, over-the-top character of its OB-Gynecologist (Carmina Villaroel).

Camp spells catastrophe

Now this doctor might have been giving sound advice, but she was made out as a babaeng-bakla–loud and campy, in bright clothes and thick make-up–an all-around ridiculous portrayal of being doctor. And let’s not even start about the fact that they were seeing an OB-Gyne for a child’s rare blood ailment–shouldn’t they have been seeing a pediatrician? A leukemia doctor? Someone else, other than this poor excuse of a doctor, really.

Who was obviously in this film as a way of bringing in the camp, something that’s proven profitable for recent dramas of this kind. But “One More Try” is about a sick child, and there is no forgetting–it seems wrong to even forget–that fact by doing camp. In truth, few of those press released campy lines work as such in the film, and one wonders if this was deliberate or coincidental.

Regardless, the lack or failure of the camp in “One More Try” allows it to just be the story of this sick boy, and how these four adults, all his parents, deal with the task of keeping him alive. Without the camp, there is a pretty interesting display of characters here that seem more complex than what we’ve seen in the dramas of this kind; there is also an amount of realness, a sense of how Grace and Jacq, Edward and Tristan get trapped in their individual insecurities, as their relationships unravel, and the absurdity of the situation becomes enough to bring them to different versions of crazy.

There was for example what Jacq put herself through to make sure that the sex between her husband and Grace be as objective and distant as possible. It might have seemed stupid, but anyone who’s gone through any version of infidelity would know how it gives us the excuse for the most insane coping mechanisms.

There was also something extraordinary about Grace’s character here, where we are allowed to see not so much and simply a mother’s love for child, but really an independent streak turned rebellion, like tunnel vision that’s gone out of control. Her ability at distance and removal, literally and figuratively in the film, is a rare portrayal of the Pinay in film. She does not beg, plead, or grovel for the love of Edward; instead she lets romance go, love for Tristan included.

Sex is sex, we are being told here, via Grace’s character. And it might happen with romance and an amount of infatuation, maybe a tiny dream of its future possibilities, but it is ultimately and truly just body. And moment. As it was on the one night stand, so it was on that other night when sex became a way of possibly saving Bochok’s life.

Locsin and Dantes save the day

Between these two women, it is Grace that you will empathize with, no matter how crazy she becomes, and that is ultimately because of Locsin’s acting chops. This is the first time in a long time that she’s been allowed to do bare bones acting, shorn of make-up and fancy clothes, without the narrative of poverty with which to explain her simplicity. And it works because Locsin is able to work into this portrayal the uncertainties of meeting up with an old lover for one, the task of sex without love for another; the engagement that is only about saving her son for one, the sense of an unfulfilled love for another. Locsin straddles these and instead of seeming confused and indecisive, reveals a woman who is in control, her eye on the ball that is getting her son well.

It is humanity that she lends to Grace. Womanhood beyond body and sex, without romance, and it is a worthy contemporary portrayal of Pinay that is a joy to watch.

Sadly, this cannot be said for Panganiban’s Jacq, who is most difficult to like throughout the film, even when she should be the one victim here. The problem seems simple enough: Panganiban does not look or sound like Jacq, advertising executive. You realize in fact that no matter the designer clothes and coifed hair, there is a stance, a voice, that points to the confidence this character needed to have so she might deal with the crisis as gracefully as her fancy shoes allow.

In the confrontation scenes, Panganiban looked like she was going through the motions of being Jacq, delivering her lines with mostly one note of anger, no matter that she might be screaming hysterically or having a biting conversation with Locsin.

Even Dantes outdoes Panganiban, where the former’s Edward is surprisingly believable, like that every guy who has settled quite happily into marriage, but who takes responsibility for whatever is in his past. The crisis of Edward is about his lack of a choice: he is not one to choose lover over wife, and he is not one to make motherhood statements about being father to Bochok.

Yet Dantes creates a character whose compassion is overwhelmingly real, and whose exasperation is far larger than the Jacq’s, waiting on her decision as he does. Marudo too, is a revelation here, rocking the scary angry man, scorned and jealous, and everything in between. In that one scene where he is allowed to be all these, you cannot but be astounded at how he survives what is also one of Locsin’s breakdown scenes.

Yes, there are of plenty breakdowns here. Yet in the end they are all happy and content, the status quo merely shifting to being focused on the strangest of extended families, and well, a boy who is apparently alive and well.

The happy ending of course is something we expect from the usual mistress dramas of the past two years. For “One More Try” this ending is its failure, crossing as it does that line between absurd and improbable, and ultimately unbelievable.

Elsewhere director Bayani says he would start a trend with “One More Try” the way he claims his “No Other Woman” kicked off those mistress movies.

I do hope that trend has everything to do with having Locsin and Dantes and Marudo in better-written roles within flawlessly told stories. And while I’m wishing his films well, might Bayani take a page from the Olivia Lamasan school of ending “The Mistress”? Written by Lamasan and Vanessa Valdez, this movie had the most real ending we’ve seen in a mainstream romantic drama since forever.

You brag about a real movie about family and celebrate its complexity? See it through to an ending that’s as complicated and as open. Your audience deserves exactly that. – KDM, GMA News Photo courtesy of Star CInema

More Videos

Most Popular