ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

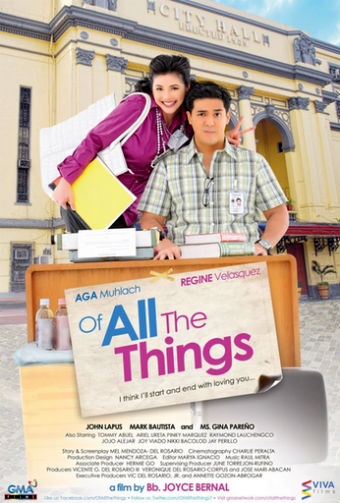

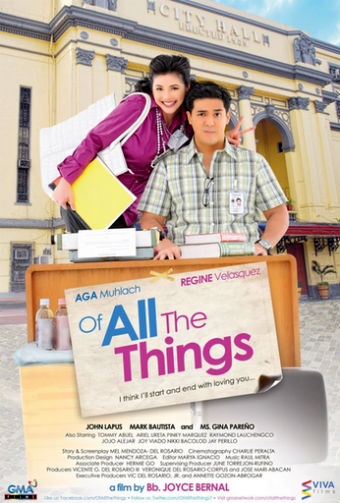

Movie review: The daring of Aga and Regine in 'Of All The Things'

By KATRINA STUART SANTIAGO

It is important to start this review off with an admission: I’m an Aga-Regine fan, as much as I am a Robin-Regine fan. Actually, I find that I can sit through any Regine Velasquez movie, including “Do-Re-Mi” and “Wanted: Perfect Mother,” and I find that I can enjoy it. And even those movies that few people saw, or looked upon with disbelief, i.e., the Regine-Piolo Pascual movie? I can watch that over and over.  There is something extraordinary about Regine’s filmography, not just because these are films written for her skill level in particular—singer as she is instead of actress—but because a look at this list of films reveals a particular romantic-comedy that Regine’s celebrity seems to have kicked off in these shores. Where there are no apologies or pretenses about her acting, and what shines through is a rare, ergo extraordinary, fearlessness when it comes to looking silly or ugly in film. This has also meant a set of Pinay characters that are infinitely more real.

There is something extraordinary about Regine’s filmography, not just because these are films written for her skill level in particular—singer as she is instead of actress—but because a look at this list of films reveals a particular romantic-comedy that Regine’s celebrity seems to have kicked off in these shores. Where there are no apologies or pretenses about her acting, and what shines through is a rare, ergo extraordinary, fearlessness when it comes to looking silly or ugly in film. This has also meant a set of Pinay characters that are infinitely more real.

There is something extraordinary about Regine’s filmography, not just because these are films written for her skill level in particular—singer as she is instead of actress—but because a look at this list of films reveals a particular romantic-comedy that Regine’s celebrity seems to have kicked off in these shores. Where there are no apologies or pretenses about her acting, and what shines through is a rare, ergo extraordinary, fearlessness when it comes to looking silly or ugly in film. This has also meant a set of Pinay characters that are infinitely more real.

There is something extraordinary about Regine’s filmography, not just because these are films written for her skill level in particular—singer as she is instead of actress—but because a look at this list of films reveals a particular romantic-comedy that Regine’s celebrity seems to have kicked off in these shores. Where there are no apologies or pretenses about her acting, and what shines through is a rare, ergo extraordinary, fearlessness when it comes to looking silly or ugly in film. This has also meant a set of Pinay characters that are infinitely more real. In Regine’s most recent foray into the rom-com, it seems that this daring has rubbed off on Aga Muhlach, as they perform the most daredevil stunt of all: they dare look their age.

Yes, in the midst of local showbiz that wants to defy age, no matter that they cannot frown nor look normal anymore, here are two actors with individual celluloid histories, so willing to be aged in front of our eyes, complete with double chins and crow’s feet, frown and laugh lines, too. And did I mention heft? This was not just a welcome respite from the fakery that's become normalized in contemporary star creation, it was more importantly a fantastic stand—conscious or not—against the imagination of an ageless celebrity.

It’s a daring that pays off, I think, even when one is startled in the beginning because one’s own gaze has been trained to think young is perfect. Once the surprise dies down, you realize that only Regine and Aga could play Berns and Emil in this film, because only they could dare make this believable.

Class has plenty to do with it, that is, social class. Berns and Emil come from similar lower middle class households, each with its own crises. Berns’ mother wants more and better, while her father is content with struggling the way they do: the mother (Gina Pareño) sells rip-offs of foreign brands, while Berns is a fixer at the city hall. Emil meanwhile is that manong you call the Notary Public, the one who sets up a desk outside government offices, the law student who didn’t pass the bar exams. His crisis is one that’s about pride: he refuses to take the bar again, his father is a lawyer and law professor, and the silence between them keeps the retake out of the picture.

The streets tide Emil over after all, even when his business is always in danger of being taken by the MMDA, even as his misery is clear as he goes about his work with nary a smile. On these streets, Emil is called Umboy, a nickname that is so of the culture of the underground economy, that you just believe it to be true.

It’s a truthfulness that is in much of this film as well, where the premises are interesting enough, the two actors believably playing the working class characters that they do. And while the happy ending is inevitable—this is the Philippines, and this is a rom-com after all—the path it takes to getting there is one that’s uniquely about the (il)legal that we live off, handled with a careful hand by this film’s writer Mel del Rosario and director Joyce Bernal, with nary a judgment. That is a feat in itself given the two lead characters and their, uh, chosen careers.

Which is not to say that this job that Berns had found after graduation was justified here as “valid” or legal. Instead it revealed it as a by-product of a system that’s inefficient and corrupt to begin with. Berns is chikadora and in control: she makes things happen. She doesn’t make promises she cannot keep, and can seem to do anything from making sure you get those licenses you need, to being event organizer for a fiesta. She’s like the Tita who is pakialamera, the one who knows it all, and in the end the one who might possibly save the day.

That the major crisis is not so much the fact of Berns’ job—given our notions of it—but the inner turmoil that is Emil’s, is the most interesting aspect of this story. Because it is obvious enough how they fall in love—like adults (yey!), without the stretched out montages of time spent together, and instead with just that easy comfort that leads to holding someone’s hand, or putting an arm around her, or holding his arm far longer than you should. But it isn’t what’s superficial that’s important here, as it is just this: you got a woman who means well, and is used to taking control; and you’ve got a man who has no ambition. And what have you got?

Conflict. Mainly because Emil does not explain, there is a silence, when it comes to the kind of crisis he lives with, that one that’s about insecurity, and so he has settled for this life of no options. Berns meanwhile thinks nothing is impossible, excluding her getting a “real” job of course. That this is the undoing, but also the reason for Emil’s reassessment of his options is the way to that happy ending.

One which is unconventional and yet is still surprisingly believable, something that—along with this entire movie—has everything to do with Aga and Regine. The latter does well as expected mainly because it is a role that is tailor-made for someone like her, who’s willing to do the more real every Pinay in these shores. It’s like a level-up of her Anya role in “Dahil May Isang Ikaw” (1999) where she drove a truck, and ate like a truck driver, and would get drunk like a man, and it all worked. The palengkera slash pakialamera layer for Berns is one that Regine does perfectly, complete with the yabang and the pagkachikadora that it requires.

Ah, but Aga is in a class all his own here, playing up as this movie does his older mestizo looks, and letting him be the most believable loser one has met in a local rom-com in a long time. What Aga is able to transcend here is not just his pretty boy roles, but also social class, where this is not particularly about a poor struggling man, and neither is this the rich boy he is wont to play. Instead it is a man who is in denial of this inner struggle that is about his own ego eating him alive. Here is Aga’s grand display of restraint and control, one that still logically works with that smile that can make any woman’s knees go weak, one that is finally and truly about him playing a role that is not only for his age, but also is a tangent that he had yet to go off on as actor.

In a land where rom-coms are the go-to projects for every artista wannabe, here are Aga and Regine, age and all, giving the commercial film industry something to chew on. Because really, if we can level-up the rom-com in the way that “Of All The Things” does, why oh why would we go back to all forms of unbelievable and impossible? Cue memories of that Angeline Quinto-Coco Martin starrer, and that one where Anne Curtis is a promo girl to Sam Milby’s university professor.

I rest my case. –KG, GMA News

Katrina Stuart Santiago writes the essay in its various permutations, from pop culture criticism to art reviews, scholarly papers to creative non-fiction, all always and necessarily bound by Third World Philippines, its tragedies and successes, even more so its silences. She blogs at http://www.radikalchick.com. The views expressed in this article are solely her own.

More Videos

Most Popular