ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

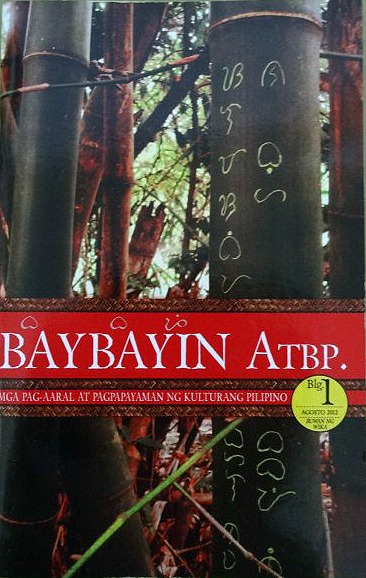

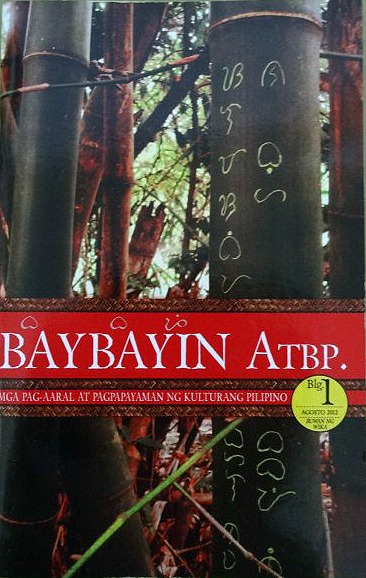

Book review: Why is baybayin relevant today?

Text and photo by IME MORALES

If you think that baybayin, or the alibata, as it has come to be known in recent times, is simply our Filipino ancestors’ way of writing, then the contents of “Baybayin Atbp.: Mga Pag-aaral at Pagpapayaman ng Kulturang Pilipino” (Teresita B. Obusan, Raymond M. Cosare, and Minifred P. Gavino) will awaken your curiosity and, hopefully, your spirit. It is true, first of all, that baybayin is the indigenous writing form invented by our great grandfathers. But it is also true that it is much more than that.

During a September 28 lecture organized by UP Tomo-Kai in Palma Hall, UP Diliman, social worker and writer Dr. Teresita B. Obusan said that the baybayin is a symbol of our culture and a means to study and understand mysticism. She explained, “We did not copy this. It was created by our ancestors and it becomes us.”

In the booklet, which was printed earlier this year and written in the vernacular, she writes: “Baybayin is a gift from heaven, given to us through our ancestors; it is a legacy for the Filipino people... and it is our responsibility to take care of it and nurture it.”

Baybayin in our daily lives

The booklet defines the 17-syllable writing system, tackles its origins and decline, and gives clear instructions on how to write in it.

The thin volume also features life works that were inspired by baybayin. Mary Ann Ubaldo, for one, creates crafts and jewelry featuring symbols from this ancient syllabary. Raymond Cosare—who said that the meeting point between the Japanese kana and our baybayin is poetry—also uses it to help people understand the relationships in their lives. GINHAWA, a non-government organization that promotes well-being through creativity and spirituality, organizes Baybayin Creativity workshops and classes.

We see these once-again-familiar symbols on works of art, clothing, even on skin as tattoos. Could it be that this age-old writing tradition is experiencing a resurgence?

Living language

The centerpiece of this slim offering on baybayin will have to be the collection of essays written by Raymond Cosare, Dr. Teresita Obusan, Rem Tanauan, Ariz Convalecer, Minifred Gavino, and Leah Tolentino.

In his “Ama, Ina, Anak,” Cosare presents an argument—and shows proof, too—that our ancestors already had a deep understanding of the oneness of two parts (the union of the mother and father to create their offspring) long before science discovered the principles of genetics. He says, “The mother and the father share not just their genes but also their preferences, hopes, and dreams.”

Dr. Obusan explains how she used baybayin as research methodology in her studies of mysticism. She calls this method “Pamamaraang K,” which has four aspects: Kasaysayan (History), Kataalan (Indigenity), Karanasan (Experience), and Kahulugan (Meaning). The syllable ka, the first one in each of the four aspects, signifies relationships, as they are used in words like kapatid, kaibigan, kaisa, kababayan, kalikasan, and many more.

Rem Tanauan, the Love Teacher and Soul Writer, writes about his experience during a Baybayin Creativity Class. He sees baybayin as a channel where deeper word meanings can flow and be understood. “It is a way for us to understand the mysterious origins of our language and our thoughts.”

Minifred Gavino and Leah Tolentino’s essay tells the story of what it took for the Baybayin Creativity Workshop-Classes to materialize. They explain that “GINHAWA offers these lessons so fellow Filipinos may come to understand their roots, awaken their creativity, and continue to be conscious about life’s important lessons.” The section ends with a series of testimonials from workshop participants.

In the final essay, Ariz Convalecer affirms that each of the 17 syllables of the ancient baybayin is alive and possesses both rhythm and wisdom. This is the secret it holds, he says, the “lihim na kahulugan” (hidden meaning) that National Artist Guillermo Tolentino talked about. “Some syllables are mild, others wild; some are noisy, others quiet,” he explains. There are playful syllables, says Ariz, and then there are those that yearn to dance or to laugh.

Let us just look at it this way: the alphabet that we use today, even to write our very own alpabetong Pilipino, is a borrowed set of writing symbols. It is only right that we understand what is truly our own so we may learn to treasure what we have been graciously given. –KG, GMA News

More Videos

Most Popular