Media today is everywhere - on television, print, radio, and of course, online. But 40 years ago, things were very different. The noise of the current media landscape is a far cry from how it was then, when an eerie silence hushed the nation. “Katahimikan nakakabingi na may pagaalala, mababalitaan mo lang ang mga nangyayari sa kuwento ng mga kaibigan, mga kuwentong may lagim sa isipan. Nawala bigla ang programa sa mga telebisyon at radyo, nang muling magbukas ay nagsasalita na si Marcos na ideniklara and Batas Militar Presidential Proclamation 1081,” writes Gene de Loyola. His words are found in the exhibit Recollection 1081: Clear and Present Danger, presented along with Balikwas: Literature under Martial Law (1972-1986).  Both exhibits are under PIGLAS, a series of art events organized by the Cultural Center of the Philippines to mark the 40th year since then-President Ferdinand Marcos declared Martial Law in 1972. Like others born after Martial Law, I’d been told often: “Mabuti pa kayo ngayon, hindi niyo naranasan ang naranasan namin noon.” With the declaration of Presidential Decree 1081 on September 21, 1972, many publications and mass media outfits were shut down, Hermie Beltran writes in the exhibit notes of Balikwas. These included national magazines like the Philippines Free Press, Weekly Graphic, Asia-Philippines Leader, and Weekly Nation, and several dailies including the Manila Times, Manila Bulletin, and Manila Chronicle.

Both exhibits are under PIGLAS, a series of art events organized by the Cultural Center of the Philippines to mark the 40th year since then-President Ferdinand Marcos declared Martial Law in 1972. Like others born after Martial Law, I’d been told often: “Mabuti pa kayo ngayon, hindi niyo naranasan ang naranasan namin noon.” With the declaration of Presidential Decree 1081 on September 21, 1972, many publications and mass media outfits were shut down, Hermie Beltran writes in the exhibit notes of Balikwas. These included national magazines like the Philippines Free Press, Weekly Graphic, Asia-Philippines Leader, and Weekly Nation, and several dailies including the Manila Times, Manila Bulletin, and Manila Chronicle.

On the vacant space of this page, an article was supposed to appear but was censored by the authorities. From the collection of Atty. Oscar Yabes, former Editor-in-Chief, Philippine Collegian

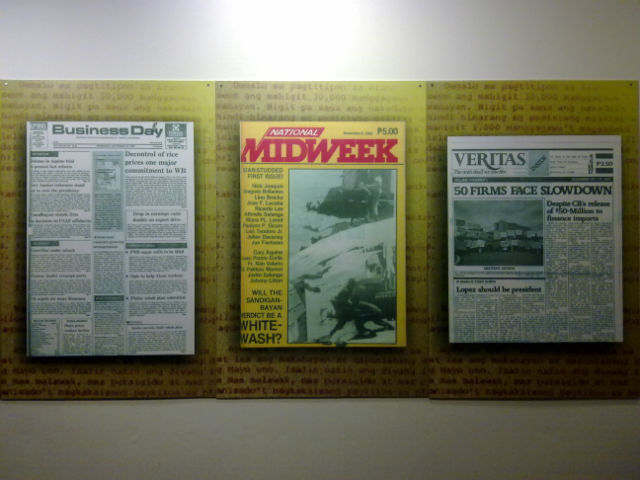

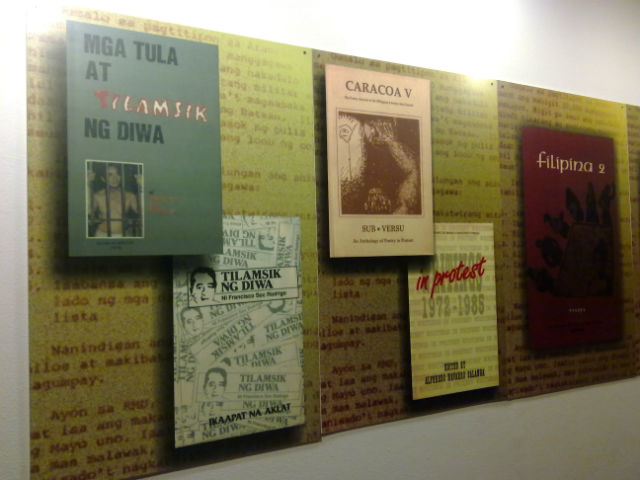

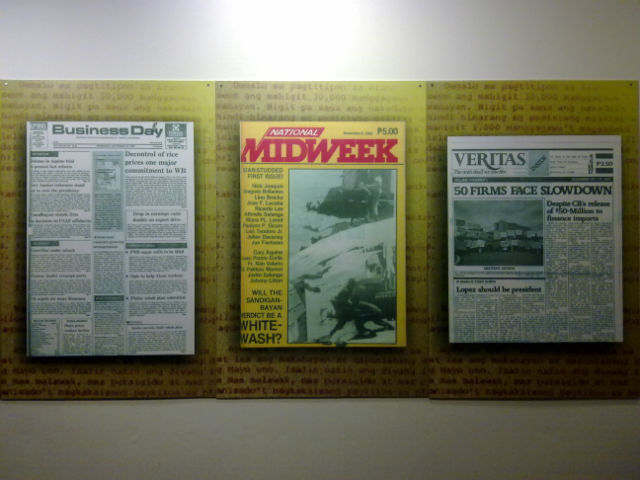

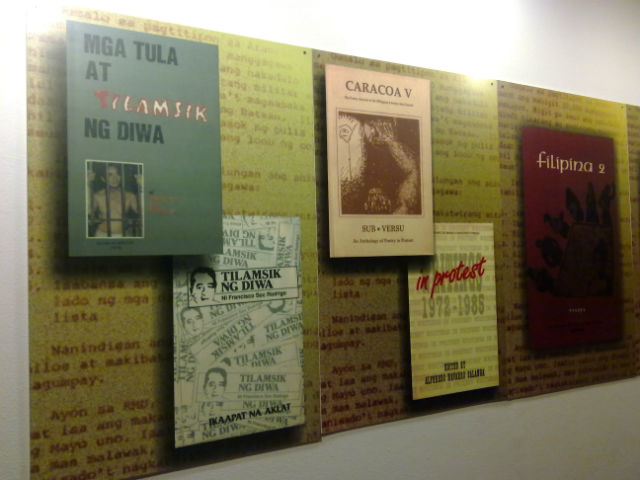

Even student organs were not spared, Beltran wrote. One of the pieces on display is a page of the Philippine Collegian, the student paper of the University of the Philippines, where a vacant space appears instead of an article that was censored by the authorities. The exhibit features various protest publications – from the alternative press to the underground press, from mass action literature to radical writings. Seeing the yellowed pages and the faded ink, I imagined what it took to create these papers. “The arduous task of resisting oppression and struggling to break free from the clutches of dictatorship, which was championed collectively by Filipino writers, journalists, communicators, artists and publishers during martial law, is emblazoned in this section titled

‘Balikwas’ (which means sudden awakening, uprising, recovery, redemption) - to remind us of our duty to be constantly vigilant of our rights and responsibilities as citizens,” Beltran wrote. In the underground press, writers used pen names. Illegal organizations or groups published the works, which they had to distribute under the radar. Those caught with such publications could be held in detention or imprisoned, tortured, and even killed.

Alternative press were sometimes dubbed as "subversive" and some were harassed by the dictatorship through military and police raids, investigations, and legal suits.

In Imelda Cajipe Endaya's “My Memories of Martial Law Years,” the artist recalled passing on subversive news and komiks from the underground. “Printmakers had to apply for clearance from Metrocom to be able to purchase nitric acid for etching, as the chemical was an ingredient for Molotov bombs,” she wrote. Forty years later, anyone with an Internet connection can publish his or her thoughts. While I don't want to be put under Martial Law, part of me wonders if literature was better then, when writing was something that could put your life at risk, posing more challenges that spurred creativity. Printed using typewriters, mimeographing machines, and even silkscreen, underground publications had no regular frequency. In contrast, today’s writers publish 24/7 – whether through mainstream media, personal blogs, and even social networks where a 140-character tweet is the fastest way to spread the news. As I looked at the crumbling manifestoes, political statements, and fliers of that time, I wondered how the current generation of Pinoys might fare in a similar situation. These types of mass action literature are still being produced, and as they were then, they are distributed during rallies and demonstrations. But majority don’t participate in these activities, and some aren’t even aware of social issues today. Even during the Marcos years, however, public apathy was prevalent. Before Ninoy Aquino was assassinated in 1983, not everyone was against the Marcos dictatorship.

Protest writings found their way in campus publications. Some were recited or performed during protest actions and in theaters. Some won recognition in literary competitions.

“There was a perceived progress and relative calm in the earlier part of Martial Law because of the suppression of negative news and the exaggeration of the positives in the controlled media," wrote artist Antipas Delotavo, one of the featured artists in

Recollection 1081. Comparing present-day conditions to life 40 years ago, Delotavo observed that “nothing has changed much; the situation is even a lot worse than before for many Filipinos... The world is more cruel now for the majority of Filipinos because of the promotion of material things (mall culture, high tech gadgets, condo living) and the pressure to acquire things. Life was a lot simpler then, as we only had Marcos to blame for everything!” I found myself agreeing with his sentiments, although after looking at the exhibit, I felt grateful that at least now, we’re able to discuss the issues and share information. This also means there’s no excuse for ignorance, this time around. –

YA, GMA News Recollection 1081 is organized by the Center for Art, New Ventures and Sustainable Development (CANVAS), Liongoren Gallery, and the Cultural Center of the Philippines. Balikwas is organized by Cultural Center of the Philippines Intertextual Division and curated by Hermie Beltran. The exhibits run from July 5 to September 30, 2012 at the Bulwagang Juan Luna (Main Gallery) and Pasilyo Guillermo Tolentino (3/F Hallway).  Both exhibits are under PIGLAS, a series of art events organized by the Cultural Center of the Philippines to mark the 40th year since then-President Ferdinand Marcos declared Martial Law in 1972. Like others born after Martial Law, I’d been told often: “Mabuti pa kayo ngayon, hindi niyo naranasan ang naranasan namin noon.” With the declaration of Presidential Decree 1081 on September 21, 1972, many publications and mass media outfits were shut down, Hermie Beltran writes in the exhibit notes of Balikwas. These included national magazines like the Philippines Free Press, Weekly Graphic, Asia-Philippines Leader, and Weekly Nation, and several dailies including the Manila Times, Manila Bulletin, and Manila Chronicle.

Both exhibits are under PIGLAS, a series of art events organized by the Cultural Center of the Philippines to mark the 40th year since then-President Ferdinand Marcos declared Martial Law in 1972. Like others born after Martial Law, I’d been told often: “Mabuti pa kayo ngayon, hindi niyo naranasan ang naranasan namin noon.” With the declaration of Presidential Decree 1081 on September 21, 1972, many publications and mass media outfits were shut down, Hermie Beltran writes in the exhibit notes of Balikwas. These included national magazines like the Philippines Free Press, Weekly Graphic, Asia-Philippines Leader, and Weekly Nation, and several dailies including the Manila Times, Manila Bulletin, and Manila Chronicle.