Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

A tribute to Doreen Fernandez's exceptional taste in everything

By AMANDA LAGO, GMA News

Doreen Fernandez is a weighty and recognized byline that is, more often than not, attached to a shrewd, witty reflection on food and how it figures in our national identity.

Fernandez is the original writer about Filipino food. Long before Anthony Bourdain glorified the lechon, and Andrew Zimmern sang adobo praises, she had been there, done that, and gone further than they or any other food critic ever had in the realm of Filipino cuisine.

Indeed, food writers who came into the scene after Fernandez’s golden culinary writing career, often ask themselves—or should ask— what would Doreen Gamboa Fernandez do?

As the late great writer of a long-running food column and many books on Philippine culinary history, she was something of an oracle. When it came to food, she had all the answers.

This is how she is most vividly and popularly immortalized in people’s minds: as the woman who approached local cuisine with a cultured sensibility, allowing food to go past the dirty kitchen and the clean kitchen, past even the dining room, and right into the heart of Filipino culture and character.

That said, legendary culinary writer that she was, Fernandez was also once a student, a teacher, a friend, and an art benefactor.

'Food for Thought' pays tribute to Doreen G. Fernandez

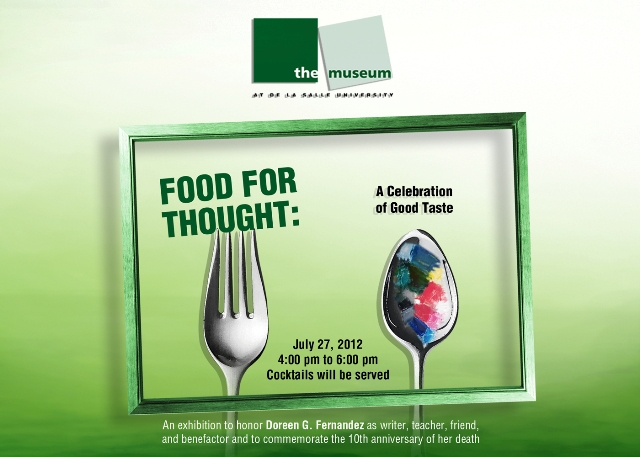

The De La Salle University (DLSU) Museum paid tribute to her in all these respects in an exhibition titled “Food For Thought: A Celebration of Good Taste.” The show opened last June 21—three days before Doreen’s 10th death anniversary—and ran until August 24.

The exhibit places Fernandez’s and her husband Wili’s art collection alongside her personal effects, which were borrowed directly from her family.

“Here is an entire life that offers all of us food for thought not only for a day, but for life. All these, in Doreen Gamboa Fernandez’s good taste,” said poet Marjorie Evasco in the exhibition notes.

Indeed, an entire life—one lived on exceptional taste—pulsed beneath the display cases and pedestals in the small, labyrinthine museum, and the exhibit unfolded in much the same way a life does.

It started at the point of youth, showcasing bits and pieces of Fernandez’s years as a model student at St. Scholastica’s College, and, later on, at Ateneo de Manila University. There, one is able to behold Fernandez’s old report cards and academic awards and understand that her bright mind shone even when she was the young and unknown Alicia Dorotea Gamboa.

Further on, behind glass boxes were remnants of Fernandez’s colorful career as an educator, during which she taught English and led the Communications department at Ateneo; counted among her apprentices such students as Ambeth Ocampo and Ruel de Vera who would turn out to have respected bylines, columns, and books of their own; and won the Metrobank Foundation Award for Outstanding Teacher in 1998.

Her award was on display along with the clothes she wore when she received it—a collage that showed Fernandez’s taste extending to her choice in clothes, and humanized for the viewer the woman whose prominence made her almost mythical.

There was more of that as the exhibit continued to unfold—more of the deconstruction of this woman’s well-defined reputation, more of the realization that beyond the iconic foodie that she was, beyond the award-winning professor and the exemplary student, she was also a beloved friend to many in the circles she moved in, evidenced by a festschrift written in her honor, and letters from such arts heavyweights as poet Jose Garcia Villa and the painter H.R. Ocampo.

Marking every step was the art work, most taken from the Wili and Doreen Fernandez collection, and some provided by Della and Ben Besa, Fernandez’s sister and brother-in-law. The art on display was yet another reflection of Fernandez’s fine taste and appetite for art.

Most of the art had something or everything to do with the intersection of food and Filipino culture. Featured artists include Omar Sayoc, Norma Belleza, Conrado Mercado, H.R. Ocampo, Ang Kiukok, Vicente Manansala, Bencab, Fernando Amorsolo, and Botong Francisco.

Curator Lalyn Buncab explained that Fernandez and her husband had donated their collection in 2003. All 416 works have proved a precious asset to the museum, and have been shown many times since, Bencab said.

Of course, there were the words. Words that seemed to jump off the pages of Fernandez’s myriad books, essays and manuscripts, presented alongside items that reflected their contents. A series of woodcuts by Manuel Baldemor, for instance, or a collection of clay pots flanking Fernandez’s last published book, “Palayok.”

A manuscript of Fernandez’s last unpublished, unfinished book was also on display, and this perhaps is the most intriguing piece in the entire exhibition. The book-that-would-have-been was given the title “Food at the very beginning: indigenous Philippine food.”

The presence of this typewritten bunch of papers will accost any unsuspecting viewer with its finality—or lack thereof. This is what a life lived in exceptional taste comes down to, the unfinished manuscript seemed to say from behind the shiny glass where it sat beyond the reach of eager Fernandez fans who would have picked it up and thumbed through it, forgetting the fact that it is a rare artifact.

It is sad to see, and sadder even to wonder what this book could have been, what discussions it could have opened, what insights it could have inspired.

At the same time, this last manuscript is perhaps a fitting illustration of Fernandez herself, of the woman whose life, legacy, and habit of exceptional taste remain unfinished, that is to say, alive. –KG/HS, GMA News

“Food for Thought: A Celebration of Good Taste” ran until August 24 at the De La Salle University Museum at 2401 Taft Avenue, Manila.

More Videos

Most Popular