Editor's note: At the height of Martial Law in the 1970s, seven out of ten Quimpo siblings joined the underground "national-democratic" revolution, drawn by its idealistic goals. But their choice ended up destroying many of their familial and friendship ties. One of the Quimpos lost his life in the movement, one is missing and presumed dead. Five of the siblings were imprisoned. 40 years after the declaration of Martial Law, the surviving siblings have written a book, “Subversive Lives, A family memoir of the Marcos years,” about the turbulent political journey of their family, and by extension, the nation. In the excerpt that follows, the youngest sibling Susan F. Quimpo writes about the day she learned her brother was killed. Lantern Parade By Susan F. Quimpo December 1981 I HAD TO GO to school. I clutched thick folders to my chest, wrapping both arms around them. There was no need for my notes that day, but I felt I had to hold on to something, even if it was only folders stuffed with notes for a test I had taken days ago. It was the last day of school before the three week Christmas break. A few exams were scheduled, but these were the exception. Even the faculty was lenient, for they too were excited about the biggest university event of the year, the evening’s Lantern Parade. The college theater group I belonged to had a good shot at winning first prize. Ramonlito, the group’s artist, had designed a six-foot lantern – its thick cardboard frame was to take the shape of a pyramid, or in keeping with the season, a Christmas tree. But as always, the group was bent on making a statement, and the well-attended Lantern parade was the perfect venue.

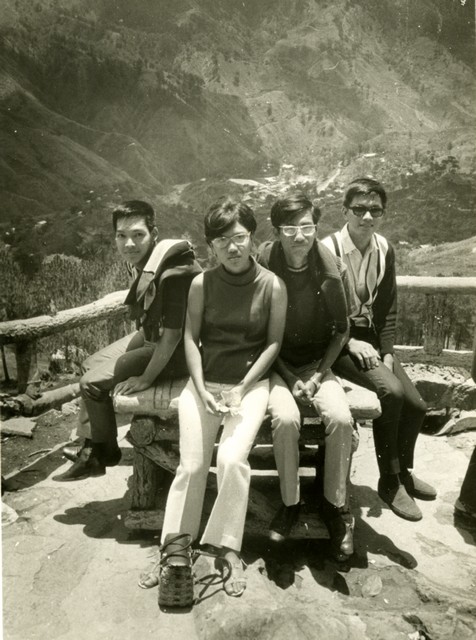

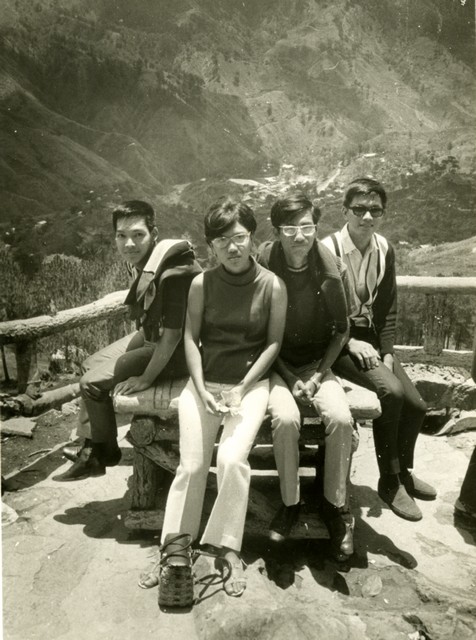

A photograph of missing ("desaparacido") brother Ronald "Jan" Quimpo (far right). A former classmate of his recently sent the author this picture. Jan is with his UP geology classmates on a hike in Montalban in 1975.

A photograph of missing ("desaparacido") brother Ronald "Jan" Quimpo (far right). A former classmate of his recently sent the author this picture. Jan is with his UP geology classmates on a hike in Montalban in 1975. The lantern’s black frame would be scored into a template of cut-out human forms, and red cellophane would be stretched underneath this cardboard scaffold. It was to be mounted on bamboo poles and lit from within, casting crimson shadows of quivering human forms. From top to bottom, the lantern would be covered with faces of society’s underprivileged as though they were trapped in the pyramid cage. The overall effect was meant to be disturbing – weary creases on a farmer’s face, gaping mouths uttering silent screams, hate clenched in fists, and eyes gawking, questioning the morality of Yuletide celebrations void of Christian charity. Ramonlito’s Christmas tree was to be wrapped in blood and garnished with rebellion. It was the season for reconciliation, however temporary. Employers gave gifts of fruit and honey-laced ham to workers they exploited all year. Seasoned protest marchers refrained converging at Malacañang, the presidential palace, to burn the American flag and Marcos effigies. And members of the communist militia, the New People’s Army, came down from the hills to visit kin while government troops pretended not to notice. Even at the university, differences were bridged as moneyed sorority girls joined the most militant activists for the Lantern Parade. I should have been excited, wanting to help piece together Ramonlito’s lantern for the competition. But joining the day’s festivities was hardly the reason I left for school that day. My sister-in-law Tina visited the family residence the night before. The fact that she came was a surprise. After two raids, it was safe to assume that our apartment was under military surveillance. It was deemed “too hot,” taboo to anyone even remotely suspected of having links to the communists, forbidden to Tina so recently released from prison. “Visiting so soon?” I chided, partly reminding her of the risk she was taking. Tina did not smile. It was unlike her not to exchange the usual greetings. Her voice was calm but her face was pale with anxiety. There was news that her husband, my brother Jun, had been killed in a barrio called Kalisitan in Nueva Ecija, a province three hours north of Manila. That was all the “courier” said; even he did not know the details.

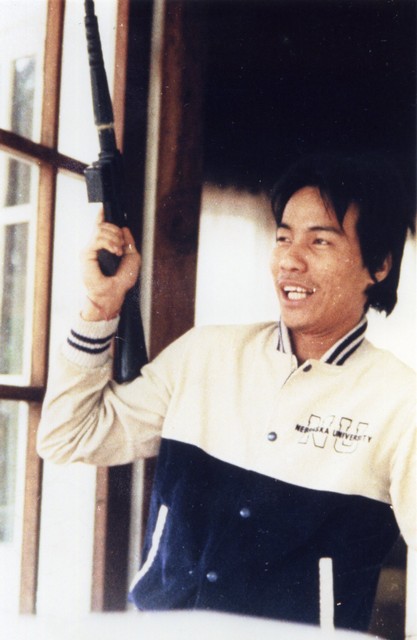

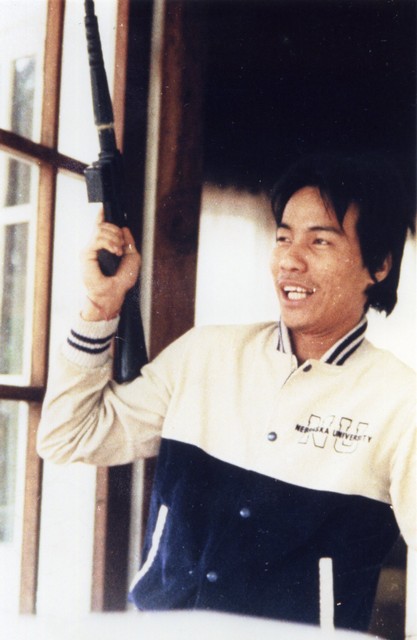

The late Jun Quimpo with a toy gun while playing with brother Ryan's children in Baguio, 1980.

Jun had often alluded to his death, and half jokingly requested that his wake be held at his alma mater, the University of the Philippines. UP was his refuge, it had become mine too. It offered an asylum for those weary of the statutes of martial law. Within its walls was freedom – freedom to organize, discuss and protest, at least for a few hours a day. UP became the breeding ground for activists and soon to be revolutionaries. Jun had thrived here; Jun had changed here. And if he were to die, it was only fitting that he came “home.” Early the next day, my sisters made the trip to Nueva Ecija. I stayed in Manila, assigned to go to school and arrange a wake for a brother I wasn’t even sure was dead. The Catholic chapel at UP had always been modest. Even at Christmas, the star lanterns and paper cutout trimmings hardly changed its homely appearance. The prayer pamphlets from the morning mass lay uncollected on empty pews. I made my way to the chapel’s administrative office not really knowing what to say. “I’d like to arrange for a wake.” “When will you bring the body?” the clerk asked, her voice crisp, almost uncaring. Secretly I thanked her; I could not have dealt with mock sympathy. “I don’t know… you see, I’m not even sure he’s dead.” I took a deep breath and fumbled for an explanation. The clerk’s reaction was one of blunt realism. She turned to a colleague and remarked that it was yet “another student killed by the military.” Only a couple of weeks before this same chapel played host to the body of a slain student activist. I walked to the Palma Hall Annex where I knew my friends would be. It was cool, the skies were clear, and the weather was perfect for the night’s festivities. I stared at the road, pacing slowly as though counting the spots where the asphalt caved in, where gravel and dirt basins caught the monsoon rains. In me, there was no room for reconciliation. The night before, the family tried piecing together a description of Jun – scars, moles, birthmarks – anything that would be distinguishable should his corpse be badly bruised or mutilated. It was hard to remember how he looked, and even harder to remember who he really was.

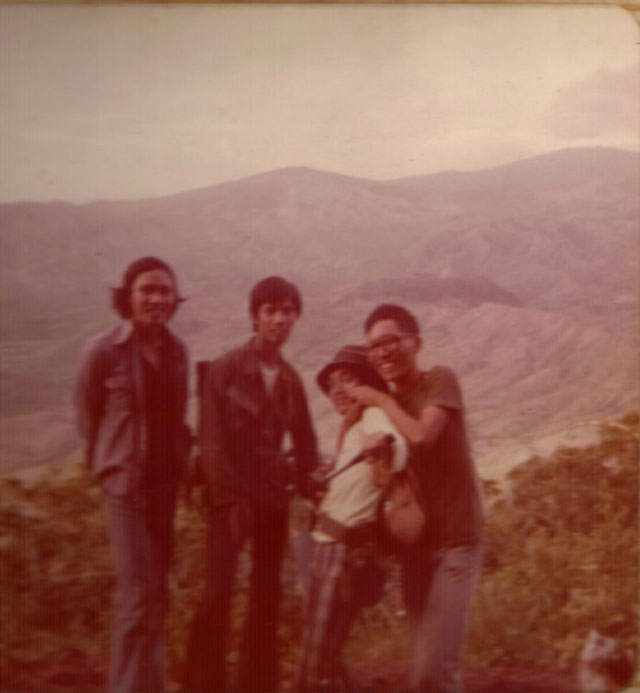

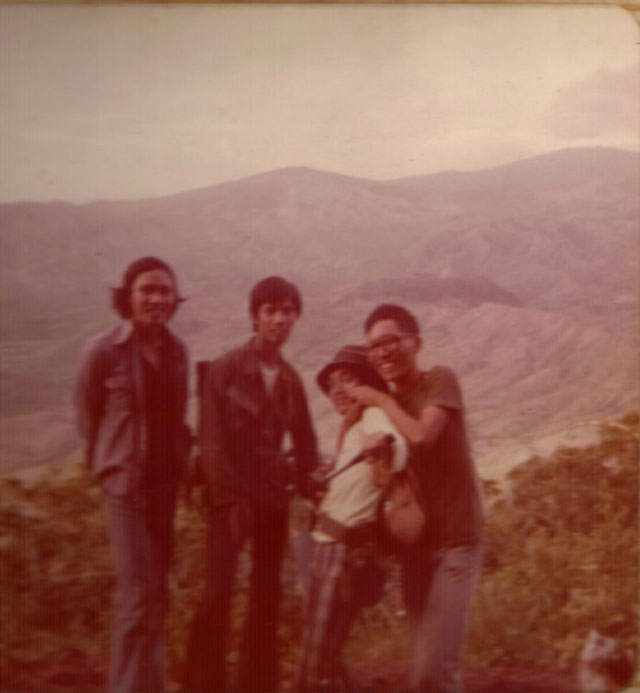

Norman Quimpo (second from right) and his wife Bernie (third from right) with friends in Baguio.

FOR THE LAST SEVEN years, I saw little of Jun and my other siblings. It would be simple to blame their absence on their avoidance of military raids, imminent arrests and detention. But I knew that my family had drifted apart long before the political persecution began. I was the passive observer who for ten years witnessed the heated exchanges at the dinner table. My parents could not understand why their children would want to organize and join street demonstrations and risk losing scholarships. What was wrong with acquiring a good college education to ensure a comfortable future? My siblings reasoned that the dictates of the times were different. The protest marches were indicative of a national movement demanding change. The hopelessness of the common man’s poverty, the corruption in government, the monopoly of power by the oligarchy, the effects of neocolonialism, and the age-old conflict over land ownership – these problems had now come to a head. And though to some the debates were little more than youthful rhetoric, my siblings spent evenings poring over Marx, Lenin and Mao in search of answers. For them, to ponder on self, family and material comfort amidst pressing times was an indulgence they couldn’t afford. THE PALMA HALL ANNEX was bustling with activity. Even the stairwells were teeming with students piecing together oddly-shaped lanterns. My friends blocked one of the corridors, littering the floor with sheets of cellophane and craft paper. Our lantern was far from done. I managed to pull Ramonlito and a few others from the crowd. Calmly, I excused myself from helping with the lantern and briefly explained my predicament. “My family received word that my brother was killed. I still do not know the circumstances.” I pretended not to notice their baffled faces and retreated for a solitary lunch. I did not want to be consoled. “Hello Lulu? It’s Susan.” Lulu was our devoted housekeeper. Constantly aware that our phone may be bugged, she had the good sense to keep conversations short. “No news, Ate Susan. In fact, no one has called.” MARTIAL LAW. No two words had more of an impact on my life. I grew up on a street called Concepcion Aguila, a five-minute walk from Malacañang Palace. With the onset of martial law, our neighborhood turned into a garrison. First came the 24-hour shift of palace guards manning wooden road blocks. Soon the roadblocks were replaced with heavy iron barricades densely wrapped with barbed wire. Then the rickety wooden police outposts on our street corner were torn down, and solid concrete stations, complete with toilets and telephones, were built. During curfew hours, the army trucks would often come and empty their hulls of soldiers. Police cars with squawk boxes joined the party. Residents needed special car passes to enter the area. Soldiers randomly checked pedestrians for IDs certifying they lived in the district. Like prisoners, we needed the military’s permission to enter our own homes. Then the military raids began, at first to ensure that the homes around the Palace were stripped of civilian-owned firearms. But as years passed, our apartment was singled out, and this time, the raiding teams were bent on making arrests. Marcos adamantly denied the existence of detention camps. “We have no political prisoners,” he often repeated to the foreign press. Yet while my high school peers spent their weekends attending family picnics, I spent mine packing cooked rice in foil and powered milk into empty tins, and helping Dad deliver these rations to siblings in three cramped “rehabilitation centers.” On Monday mornings, my classmates would ask what I did for the weekend. “I stayed home,” was my usual reply.

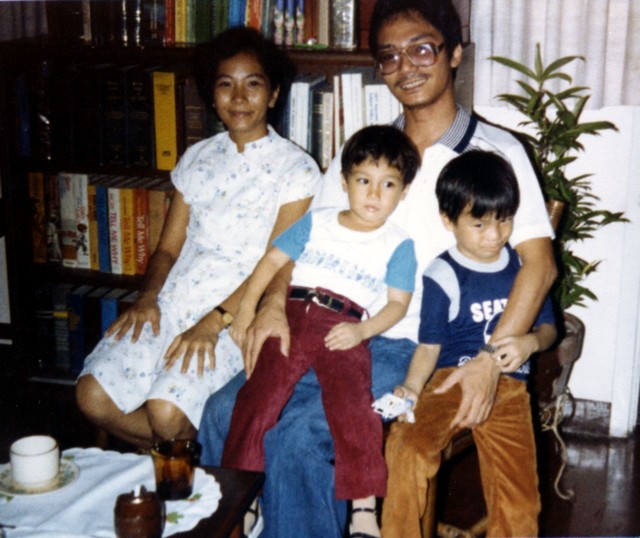

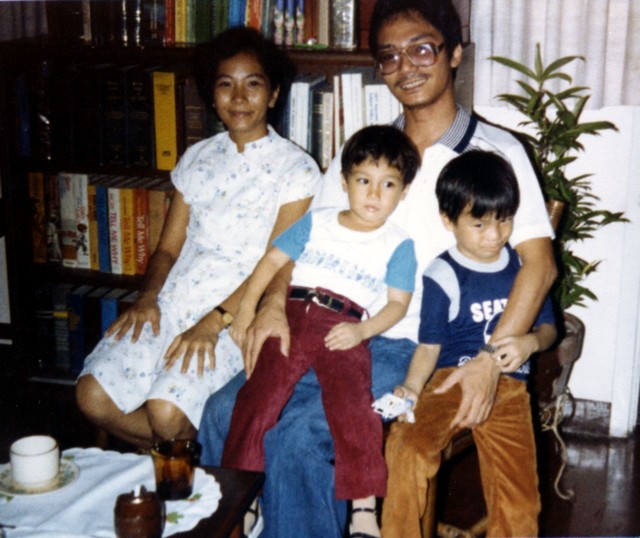

Ryan with his wife Popet and two children Oliver and Kulay before seeking political asylum in Europe.

IT WAS NEARING DUSK and the students now hauled their lanterns of various shapes and sizes into the street facing Palma Hall. Masked by nervous giggles, they spied their neighbors’ lanterns. In hushed tones, comments of awe and ridicule were exchanged. A few sang Christmas jingles, many to the tune of popular TV soap commercials. I decided to momentarily join the crowd to satisfy my curiosity. “Susan! We’re here!” a member of the theater group called above the growing throng. I watched and smiled; in jest, my friends swore as they took turns trying to suspend the lantern from bamboo poles. “It’s far too heavy, I warned you, this would never work! Watch the lamp, it’ll set the cellophane on fire!” The lantern wasn’t perfect, but it was done. I weaved into the group and took my turn at badgering the lantern bearers. It wasn’t long before a few friends called me aside. To my horror, they said in all sincerity, “We heard about your brother, our condolences.” “No, no one said he was dead!” I snapped, more upset than angry. I turned away and again retreated. Martial law forced the open opposition movement underground. When military repression ensued, the call for armed rebellion was justified. Almost overnight, the label “student activist” was no longer apt. The newspapers were quick to christen the members of the underground movement with new names: communist insurgents, terrorists, guerrillas, rebels. Yet my personal lexicon remained unchanged; in my mind, they were simply family. Though I was baffled by my sibling’s continued loyalty to the “revolution,” their courage had won my respect. What I could not accept was that this movement, the revolution, had the power to draw its members away from their lives and their families, yet could not care for its own. Where were the

kasama, their comrades-in-arms, when my brothers Jan, Nathan and Norman were arrested and maltreated by the military? Where were the

kasama when Jan’s head was repeatedly immersed in a commode filled with urine, when water was injected into his testicles, when his feet were doused then jabbed with live wire?

Taken during the last family reunion of Quimpos in Siquijor Island in 2009. The surviving Quimpo siblings (standing left -right) Nathan, Lys, Ryan, Norman; (seated left-right) Susan, Lillian, Emilie and Caren.

Our family did not hear from their

kasama when Nathan was stripped naked and clubbed until he was nearly unconscious. No assistance was offered when my sister Lillian was missing for weeks, and Dad made the rounds of prisons in search of her. Does one cease to be a comrade upon his or her capture? This revolution had stripped my family of any semblance of normality. It had promised victory, yet it only brought separation, torture, and now possibly Jun’s death. “Lulu, I’ll be home in an hour.” It was my nth call to Lulu; she still had not heard from my sisters who ventured to Nueva Ecija. I refused to worry about their safety; to do so would only add to the day’s futility. It was nearly ten o’clock when I arrived home. I was exhausted though I had spent most of the day idly walking around the UP campus. As usual, Lulu had dinner waiting for me. She said my sisters were not back nor had they called with news. “Did anyone bother to call?” I asked in total resignation. “

Ay, Ate, someone did call. I can’t recall his name, but he said your group won first prize at the Lantern Parade.”

- GMA News  A photograph of missing ("desaparacido") brother Ronald "Jan" Quimpo (far right). A former classmate of his recently sent the author this picture. Jan is with his UP geology classmates on a hike in Montalban in 1975.

A photograph of missing ("desaparacido") brother Ronald "Jan" Quimpo (far right). A former classmate of his recently sent the author this picture. Jan is with his UP geology classmates on a hike in Montalban in 1975.