ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

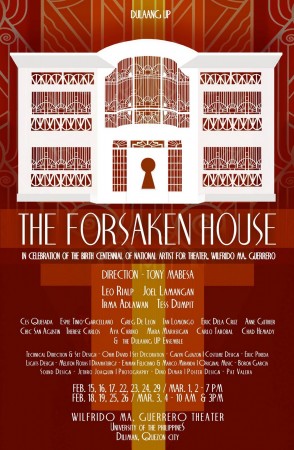

Theater review: Suffering through 'The Forsaken House'

By Katrina Stuart Santiago

And when I say suffer, I mean “Why exactly am I watching a soap opera unfold onstage?” I mean, what happened to Wilfrido Ma. Guerrero’s original text? I mean, where has context gone?

And when I say suffer, I mean “Why exactly am I watching a soap opera unfold onstage?” I mean, what happened to Wilfrido Ma. Guerrero’s original text? I mean, where has context gone? Or maybe just: is there a dramaturg in the house?

Apparently there are two, according to “The Forsaken House” program, not that you’d feel or see it as you sit through this production.

Because here, Ma. Guerrero’s text unfolds like a long-drawn out soap opera of family. Here, the family of nine —nine!— seems to be embroiled in nothing but the most superficial of dramas, borne of and premised only on the patriarch who kept family on such a tight leash. It would seem good enough, but it is nothing but a myopic view of, if not the smallest tiniest imagination of what is a large —no, huge!— text.

This is 1940s Manila! A time and place burdened by American colonialism and World War, but also tinged with hope for freedom from both. That stage and everything on it —including the actors— should’ve transported us in time, made us feel the claustrophobia that is contingent upon a house forsaken by the strict patriarch on the one hand, the changing times on the other.

Instead, all you get is a stage that is a living room farthest from looking like it’s “richly furnished”, which is what the text requires.

You get dark and dreary and just old, not at all a set that will automatically tell you, ah, it’s another time altogether and not some house that’s been untouched since the 1940s.

And then the characters start appearing onstage, and you realize that sometimes, no matter how great your actors, even they cannot save a production.

Which is not to say that this cast was brilliant. Goodness, no.

On opening night, all three actors and three actresses who played the children of Don Ramon and Doña Encarna looked totally ill-prepared for this play, awkwardly moving across the stage, doing their blocking as if we were supposed to know exactly where their markers were put.

There was no forgetting that we were watching actors acting here, and if they thought this was the way to establish that these are not well-adjusted kids, then that isn’t at all how it came off.

Instead, it came off as a bunch of actors too young to know what their characters were supposed to be about —in fact, a bunch of young actors who weren’t skilled enough to handle the complexity of their characters.

Because the complexity is that each one of them, each child, was supposed to be symbolic of the changing times, as they were symptoms of the decay that’s about the house, yes, but also that could only be about the impending war. Because these kids weren’t supposed to just come off as rebelling in different ways against their strict father who was nostalgic for the Spanish past (speaking authentic Spanish to boot!) and subservient prayerful mother.

There was a rationale to one daughter wanting to be a nun, another deciding to elope, and the youngest getting inexplicably sick; a rationale to the son who wants to leave, the other who gets into trouble, and the other who gets a sexually transmitted disease.

Yes, these characters were pregnant with meaning, ripe with possibility. But none of that would’ve been obvious to those who don’t know the original text by Ma. Guerrero.

And let’s say we were to let go of the symbolisms in these characters —which seriously is a stretch— what we’re left with is a set of young actors and actresses who also didn’t at all engage the audience in their collective travail of being oppressed by this house that caged them.

You know, at the very least, that this should’ve come off as a version of the Von Trapp kids, who were caring of each other, played and had fun beyond the purvey of the father, whose presence practically rendered them as soldiers. Sadly, one could miss altogether that this set of six actors were siblings in that forsaken house.

Even more sad, without those actors doing their roles well as an ensemble and individually, there is no clear sense of how strict Don Ramon (Leo Rialp) actually was, no sense of how this patriarch was in control of his children. We weren’t supposed to just believe that because it was being said; we were supposed to see the effect of that kind of overt control in the dynamic within the household, and on that stage.

But, save for the kids disappearing into their rooms and looking at their feet when spoken to, there was nothing here that made Don Ramon seem larger than life —which is to say there was little sense in his undoing, too. Rialp was one of the better actors here for sure, but even he couldn’t carry it all on his shoulders.

Nope. Not even with Irma Adlawan playing Doña Encarna and Ces Quesada as Tia Pelagia. In fact, the latter, along with Tio Carlos (Menggie Cobarrubias), was supposed to be symbolic of the more liberal, changing world that Don Ramon abhorred. But here, both just seemed like stock foil characters with nary contextual complexity.

Which does just bring us back to: Where were the dramaturgs here? Where is that kind of analysis of the text, that also becomes direction and vision for its performance? Again, there are two written in the program. There might as well have been none.

The only thing that could make this any worse? The atrocious English here. Of course they had memorized their lines, but across all these actors —across all of them, young and old— what one is treated to is Filipino English of the present, one that isn’t even consistent across all the actors.

Here was a grand display of the diverse ways in which we speak English, none of which felt like we were in 1940s Manila.

Not even 20 minutes into “The Forsaken House”, I thought: Repertory Philippines should be doing this play. Repertory Philippines would be able to transport me to 1940s Manila, do that “richly furnished” living room well, and would have actors who’d know to do one kind of the correct English like the back of their hands.

And they’d let me get lost in this space, these moments, and build context for me in the process.

That realization might be the best thing to come out of my having suffered through “The Forsaken House.” — TJD, GMA News

Katrina Stuart Santiago writes the essay in its various permutations, from pop culture criticism to art reviews, scholarly papers to creative non-fiction, all always and necessarily bound by Third World Philippines, its tragedies and successes, even more so its silences. She blogs at RadikalChick.com. The views expressed in this article are solely her own.

Katrina Stuart Santiago writes the essay in its various permutations, from pop culture criticism to art reviews, scholarly papers to creative non-fiction, all always and necessarily bound by Third World Philippines, its tragedies and successes, even more so its silences. She blogs at RadikalChick.com. The views expressed in this article are solely her own.

More Videos

Most Popular