Kidlat de Guia’s tragic, triumphant exit

Before the son Kidlat Senior, there was the father, Kidlat Junior. I got that right – Kidlat Tahimik, the legendary filmmaker who grew up and went to Wharton as Eric de Guia, renamed himself after his eldest son, Kidlat de Guia.

Kidlat Jr. told me this story himself some years after I met him in Sagada in 1984. He was the long-haired shamanistic figure playing the nose flute in the distance while sitting in a small Sagada playground. When I aimed my telephoto lens at him, I recognized him as the man whom I had recently seen speaking at the Goethe Institute after a screening of his landmark film, “Mababangong Bangungot,” an indie film before even the word indie and the first one I had ever seen. Startled into elation, I blurted out, “Kidlat!” He stopped playing and called me to come near, and that’s how we became friends. Nearby was his son Kidlat de Guia and a friend monkeying around the playground while the father was playing the nose flute. Kidlat senior was then just eight years old, already a constant companion of his dad. Two years later he would appear in historic film footage shot by his father in Baguio at the height of the 1986 people power revolt. That became part of a dreamy Kidlat Tahimik collage of images about those years presented as a cinematic letter to his son, “I am Furious Yellow.”

I would visit Kidlat Tahimik in Baguio often in the '80s and '90s as I covered Cordillera issues, getting his offbeat take on history and indigenous culture, or as he called it, the “indigenius.” His son Kidlat Senior then was often around, meeting his father’s friends, observing, imbibing Igorot culture and the sensibilities of the cosmopolitan community that Baguio had become.

By the time he entered UP Diliman, Kidlat Senior had become his own man, a visual artist who was experimenting with photography. But Kids, as his friends called him, was also proudly his father’s man, championing his work and promoting the virtues of being independent, indigenous and even eccentric.

One artistic pinnacle was reached with a solo exhibit of his art photography at Galerie Duemila in 2015 when he was 40.

READ: Art review: Maytime playtime: Kidlat de Guia’s woven art

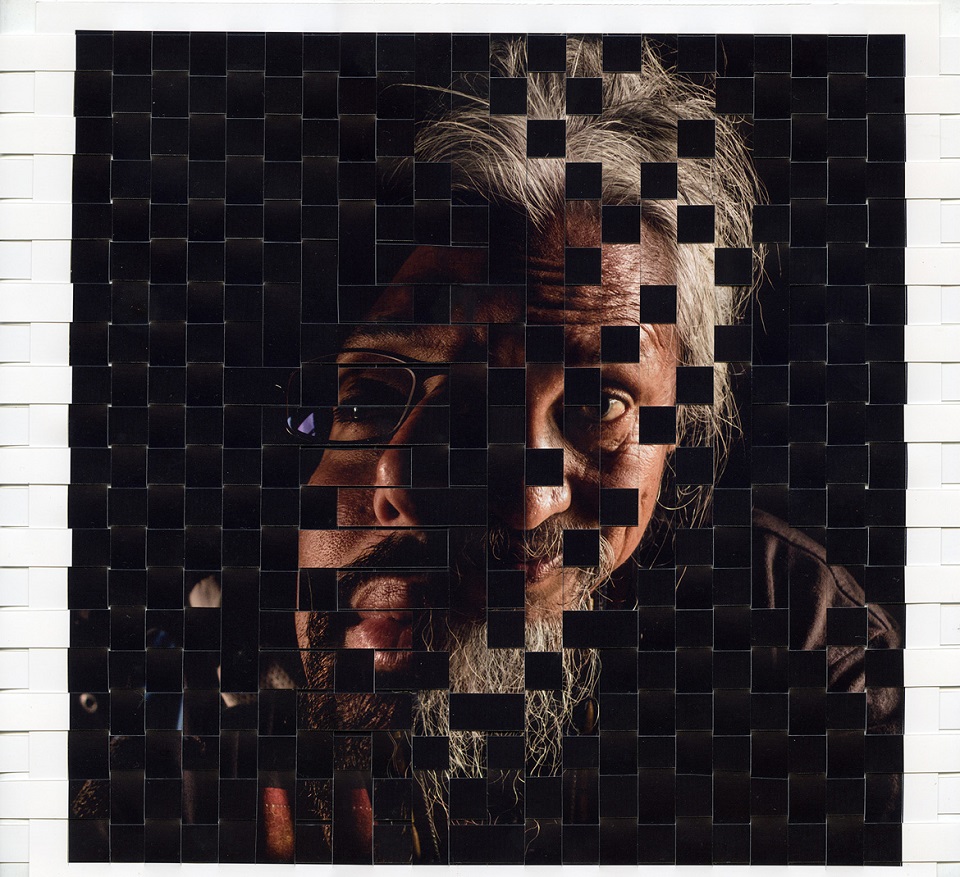

A series of exquisitely original arrangements of cut-up pieces of old and new photographs woven together to express mood and memories, the exhibit was an homage to the ancient craft of weaving in the Cordillera as well as a fresh frontier for photography.

It was also in a way an homage to his father, who pioneered in honoring the native in an ingenious application of a global medium. Sure enough, among the frames in the exhibit was one that wove the head shots of the two Kidlats, half of the father’s face staring at the camera grafted onto half of the son’s bearded gaze at some far-off place.

Kids seemed to be assuring his dad that he was taking the torch and running with it into the future.

Many children of legends struggle in their shadows, feeling the weight of expectations, especially if they’re namesakes. Kids always seemed to bear that weight lightly like it was a stroke of good luck. Besides, he was named Kidlat first.

Kidlat the father often reminded me that fatherhood always trumped career when it came to his priorities. Who knows how many more films he would have done if that weren’t the case. But fatherhood to him was a career, weaving his sons into his work in myriad ways, from making them stars in his movies to allowing them to play with expensive equipment from a young age.

That father-son weaving was what took place in the last six months in Spain in their last great collaboration, a monumental exhibit on Magellan, his beloved and enterprising Filipino slave Enrique, and the epic battlefield triumph of Lapu-Lapu in Mactan. The deep and insidious effects of colonialism were a theme that had been the father’s obsession for much of his artistic life.

READ: National Artist Kidlat Tahimik launches historical exhibit in Madrid’s Retiro Park

Kids was in Madrid this month to help his father close the exhibit and take apart the menagerie of elements, like the giant Cordillera rice gods, the wooden Trojan horse with a film camera for a head, and his own art employing the magical weaving of photographic tiles into images of Rizal and other Filipino heroes printed onto sails, evoking the ships that connected Spain to the Philippines.

In the 500th anniversary year of Magellan’s fall in the Philippines, the arrival of the two Kidlats in the land of the colonizer to celebrate Filipino resistance in such a grand way was their pièce de résistance, if not their greatest artistic achievement then a helluva catharsis for this pair of indio-geniuses.

Losing Kidlat de Guia at 46 is a tragedy that is being felt by many, especially his close-knit family, and his wife Lissa and their young children Kalinaw and Amihan.

But by devoting his last months to helping remind the world of the power of art to slay demons and transform our lives, Kids went out triumphantly.