'Aswang': The drug war documentary cuts to the bone

Filmed over the course of two years, "Aswang" was supposed to have its Philippine premiere at the Daang Dokyu documentary film festival on March 16, after having been debuted at film festivals around the world, to critical acclaim.

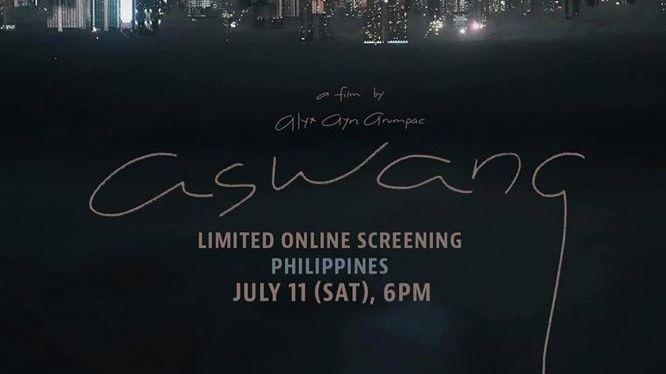

But with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic delaying the Daang Dokyu festival, "Aswang" premiered this weekend online instead, where it is available to stream for free until 11:59pm on Sunday.

The film speaks volumes about its intentions to not feature any police or politicians in the narrative, focusing instead on the street level - the human impact- of the drug war.

Shot almost entirely at night with a blue, metallic tinge, the bleak, dystopian nature of the lives onscreen is palpable; what flashes of color cross the screen come almost exclusively from harsh fluorescent, neon, and police lights.

This is the city, largely unchanged from Lino Brocka’s "Maynila sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag" (1975), a squalid metropolis struggling under the weight of poverty and despair. Where that film painted a fictionalized account of life in the Philippine capital, "Aswang" is all too real.

While the documentary covers a lot of ground, a significant chunk of the narrative centers around a young boy, Jomari, who sees firsthand the effects of the war.

His friend, teenager Kian Lloyd delos Santos, was infamously killed by police officers who claimed he drew a weapon on them, despite CCTV footage showing the boy being dragged off by plainclothes operatives moments before his murder.

Jomari’s parents are in prison over drug charges, leaving the child to fend largely for himself in the slums where much of the documentary takes place.

Midway through the film, Jomari disappears, shifting the focus towards finding him; while the search is drawn out for longer than was probably needed (he turns up fine), the unease generated by this section of the film is one that everyone of Jomari’s economic class must contend with on a daily basis.

Which brings us to the film’s main argument: brutality notwithstanding, the war on drugs is more of a war on the poor than anything else. While small-time pushers and users are gunned down in front of their families, the drug lords who supply them are wealthy enough to make sure that they will never be punished for their crimes.

Perhaps the most striking thing about "Aswag" is how the impoverished are shown to have seemingly accepted their lot in all of this. They may be anguished by the loss of their loved ones, but they’ve also come to the point that they’re shockingly matter of fact about their inability to remove themselves from the perils of “collateral damage” that occur with alarming regularity.

This regularity is driven home by the thriving practice of the 24-hour Eusebio Funeral home, which has no shortage of new arrivals, though the proprietors seem to have no issues with this.

One of those shown to be pushing back is Redemptorist missionary Brother Jun Santiago, who has devoted himself to not only consoling the families of the slain, but doing his part to document the killings.

Working out of the Baclaran Church, Brother Jun resembles a field journalist more than a man of the cloth - armed with his camera, Brother Jun helps those left behind, chronicling their stories, while aiding in their funeral expenses.

In Filipino folklore, the term “aswang” refers to a shapeshifting demon that preys on people foolish enough to look into its eyes under cover of night. While appearing regularly in horror films, comics, and television, the legend of the aswang was put to perhaps its most infamous use by the CIA in the late 1940's.

Following World War II, CIA agents decided that the best way to quell support for the growing Huk rebellion was to kill its supporters in the night and leave their mutilated corpses in public to discourage thoughts of dissidence, with blame being ascribed to the legendary creature. Having watched Arumpac’s documentary, one doesn’t need to be superstitious to see that there are still things to fear in the night. — LA, GMA News

Aswang is available to rent on vimeo here.

A life-long lover of film and pop culture in general, Mikhail Lecaros is a writer who loves coffee and sleep in equal measure. Check out his Three Point Landing and Sub-Auteurs podcasts for more.