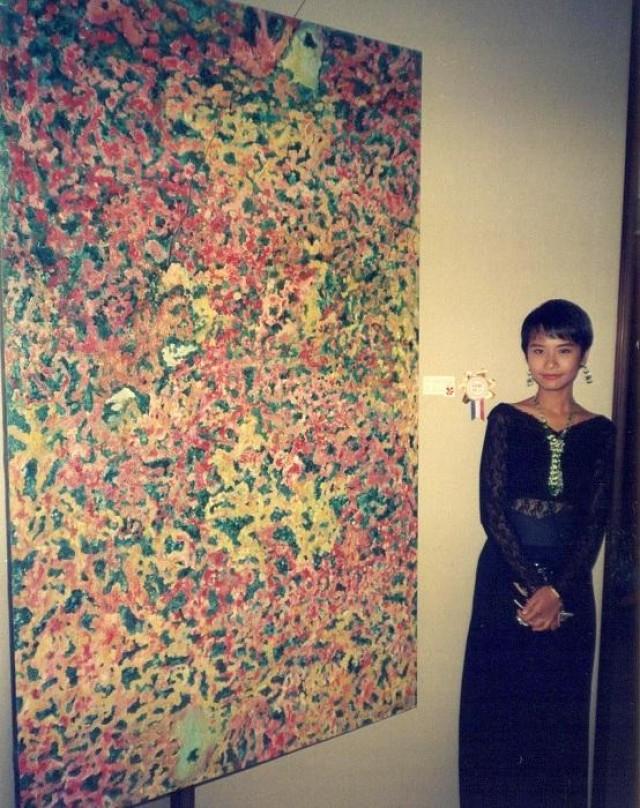

Remembering Maningning Miclat, painter, poet, interpreter, and teacher

China-born Filipina painter, poet, interpreter, and teacher Maningning Miclat clasped a picture near her chest, took off her shoes, and fell backwards, facing the sky from the seventh floor of Manila’s Far Eastern University on September 29, 2000. A lower awning at FEU’s education building cracked her spine. Her face was not disfigured. She looked lovelier after her mad gallop to nothingness. She was 28.

Eighteen years later, her self-laceration has blossomed for other painters and poets, thanks to the establishment of The Maningning Miclat Art Foundation Inc (MMAFI) by her parents in 2001.

Every two years since 2003, MMAFI would recognize painters and poets writing in Chinese, English, and Filipino. It has since given 24 awards.

This year, the MMAFI has chosen artist Jessica Lopez's "Motion of Life" — made of fish bones on plywood — as the 8th awardee during "Ginugunita Kita," a gathering at the FEU auditorium on Wednesday, September 26.

The memorial essayed Miclat’s poems made into music by composer-pianist Jesse Lucas, and sang by her sister Banaue Miclat-Janssen with cellist Renato Lucas.

MMAFI must now expand its advocacy to art as suicide intervention or de-stressing process, observers said.

Clues of Miclat’s suicide are easier to trace from her paintings more than her poetry. Her book, “Voice from the Underworld – a Book of Verses,” is a collection of mesmerizing love poems. Her poems on heroes who ended (in the late 1800s) more than 300 year old Spanish colonial era are not about political debates but of heroes in love or pining for lost or far-away lovers.

A painting tells all

Soliloquy, Miclat’s remarkable painting, is a black and white acrylic on 11 panels of four by eight feet plywood, done in 1990. The panoramic piece simulates endless, repetitive, and unbearable sea waves with cosmic energy, as if pulled up by the moon. Also, they are like serpentine flowers with voluptuous and restless petals that incessantly protrude and retract, that fiercely dart from light to dark.

Soliloquy has dwarfed all other black and white paintings ever done by Filipino artists who have explored the tension of yin and yang. Maningning has plumbed her underworld’s tension — as if she herself is her own painting.

Soliloquy was made in 1993 following her solo side-trip to Siquijor and to Iligan with friend Kelly Ramos, when she, a University of the Philippines student, became a writers' workshop fellow of the Siliman University in 1991. It graced the Cultural Center of the Philippines for four months.

Miclat’s sense of being divided like a lost soul between China and the Philippines, has been blamed for her suicide.

“It was angst. Our children Maningning and Banaue were born and educated in China. My husband Mario, a member of the leftist Student Cultural Association and Kabataang Makabayan had just graduated and I, an engineering undergraduate and member of Progresibong Samahan sa Inhinyeriya at Agham at the University of the Philippines (UP) when we went to China as observers in August 1971. We exchanged bullets and were married underground style in a house of a comrade in Quezon City in May 1971. Maningning was 14, and Banaue was seven when we came back to Manila in 1986. They were in touch with their friends in China. Maningning never hinted of a toll in loving two cultures,” narrated Alma Miclat, Maningning’s mother and president of MMAFI.

Loving two worlds is declared (like a command) in Miclat’s poem, “Sensation”:

Remember this heart, China

For in your vastness I am raised

As I commit myself to you, Filipinas

For in your ground my root is found

I was one with you, China

And I will always long for you

I ought to know you with all my heart

I embrace you, Filipinas

The poem reveals Miclat’s sense of poetic space and heart-wrenching separation from where the soul and spirit have taken roots.

When Chinese leaders stopped protesters at Tian An Men in 1989, Miclat, then 17, intentionally said goodbye to China. “I was a college freshman (who took up BS. Mathematics) in UP Baguio when the crackdown took place. I stopped publishing in World News after struggling with one last essay and a few poems in Chinese. Then, I decided that I was an outsider. Chinese was no longer the language for me,” she wrote in a post-script of the “Voice”.

The Tian An Man incident heightened her sense of paradise and childhood lost in China. Carving China out of her heart (after she understood its politics) in 1989, she looked for herself in Filipino and English, languages she mastered in Manila in 1986.

She then turned to translation, which for her, went beyond a linguistic exercise and became a search for being. “I have worked as an interpreter many times (even in diplomatic gatherings between Chinese and Filipino officials), and I believe it is time for me to go back to what I left behind as a child, in Chinese, and reinterpret them in English,” she wrote in the “Voice”.

Miclat’s poetry and paintings (expressions that objectify pain and joy) failed to protect her from fatal lower depths. Despite the socio-political awareness that her parents honed in UP and in China, she became an artist with inward terrorism of the soul – unlike the social realists who emerged in the '70s with outward focus on angst as class-based and neo-colonialism as a source of oppression.

Journalism also failed to tame Miclat’s precocious intensity. Manila’s World News Filipino-Chinese publisher Florencio Tan Mallare asked her to write regularly when she was 15 in 1987.

James Na, World’s literary editor, published her Chinese poems, including poems of Filipino poets that she translated to Chinese. Na published her first book of poems “Wo De Shi (My Poems)” in 1987.

Explaining other reasons for Miclat’s tragic goodbye, her friend, sculptress Aba Dalena, said, “She was burned out. She was a full-time master’s student; a full-time teacher; and a full-time artist preparing for shows. She was worried. Her father had two angioplasty procedures and a quadruple heart bypass in 1998.”

There was an Italian journalist when the boat of Greenpeace docked at Manila Bay, before its trip to China, in 1998. “She painted his portrait. Maybe she had depression. But I remember she was happy teaching at FEU,” said her mother. “A day before she died, she crushed sili in one hand to ease her pain,” recalled her sister Banaue.

“It was poetry (not people, not being displaced or rejected),” her father insisted when asked who to blame - at the wake at Funeraria Paz on Araneta Avenue in 2000.

Since her death, several groups have been established to help artists and non-artists cope with stress. — LA, GMA News