Until January 23: Cian Dayrit's 'Busis Ibat Ha Kanayunan or Voices from the Hinterlands'

A thatched roof shades the stairwell that leads to Bellas Artes Outpost’s exhibition hall. Wood and bamboo benches face the walls while a haunting, Ayta wedding hymn (Ambahan, recorded by Dr. Felicidad Prudente in 1973) floats from speakers; dried leaves litter the floor.

In this calm and idyllic setting, the Aytas’ struggles and aspirations find temporary accommodation in a show that eloquently articulates a cultural crisis.

An inquiry into Bataan’s history preceded Cian Dayrit’s exhibition, "Busis Ibat Ha Kanayunan or Voices from the Hinterlands", part of an ongoing project for his residency at the province’s Bellas Artes Projects.

His research revealed a glaring omission. “I’ve been going around the museums and realized that all of the historical and cultural institutions were talking about the Bataan Death March, World War II, the Japanese occupation. That’s what everyone —even the [province’s] locals — knew of Bataan,” Dayrit said. The province’s Aytas —descendants of what is believed to be the Philippines’ first inhabitants — were hardly mentioned.

He would find out too about the lack of interaction between province’s mga kulot (curly-haired, as the Aytas refer to themselves) and non-Aytas (mga unat or straight-haired), which is alarming considering their proximity to each other. “Yes, definitely...politically, economically, socially, culturally,” was the Dayrit’s emphatic response when asked if the Aytas felt excluded.

“Like any other indigenous community, napupunta sila sa peripheries ng society. Nala-land grab, nare-red bait, hina-harass ng armed forces, na-e-exploit sila. I just could not ignore the Aytas,” the artist continued.

As for the show’s intention, the artist has a realistic ambition: “For it to become a start. Kasi, I guess we can say na having a museum [later on] that the Aytas themselves authored can be an interesting gesture. For them to have a space— that’s not run by any government institution or NGOs—where they can articulate their plights and represent themselves.”

His role is clearly defined as well. “Ayokong maging parang NGO na nagmamarunong kung ano yung kailangan nila para sa ikabubuti ng kinabukasan nila. Kailangan natin ng mas appropriate na paraan kung pano sila ma-integrate with contemporary society talaga. Kasi it’s not our role to handle or keep them in place. As far as I’m concerned, tawid lang ako. My position is really just, ‘wag ka magmarunong, man.’ This [exhibition] is me talking to them. Not for them.”

It is tempting to romanticize the exhibition given the atmosphere. But Dayrit’s aggressive staging of a metal sculpture (revered Ayta elder Apo Alipon) right smack at the entrance hammers in a message.

Its pose — right knee to the ground, right hand extended with fingers lightly touching the sculpture’s base — echoes the gesture popularized by American football players as a protest against social injustice.

As an avowed leftist, Dayrit conveys a call for resistance. “Gusto ko’ng makita sa events in their local history na lumaban sila, at yun ang gusto ko’ng i-continue nila. Kasi, feeling ko kailangan nila’ng maging militante. Yon yung gusto ko’ng mangyari para sa kanila,” the artist said laughing.

In a corner behind the sculpture, Dayrit simulates the burning of an effigy with an allegorical monster (Inuling na Imahe ng Berdugong Manlulupig) standing atop a pile of charcoal, a material identified with the Ayta culture and in recent times, a source of income.

There’s a shrine (Palyon Noon, Ngayon at Mamaya) where one finds tokens of devotion and pagan gestures.

This includes battery-powered votives, offering bowls filled with coins, garlands of amputated thumbs, alongside a reimagination of a traditional Ayta pottery. To this assemblage, the artist cleverly grafted his leftist ideologies in the cement-cast anting-antings.

The Aytas share the exhibition space as collaborators and subject: Their output brings a heartbreaking poignancy to the show. On a wall hang photos taken by the Aytas themselves. The montage reveals everyday scenes, their habitats, portraitures and, in the case of a woman in a deftly draped red dress, a rare stylistic expression. As stated in the show’s guide, the project “is an initial attempt to encourage the community members to document and author their own visual representation through photography.”

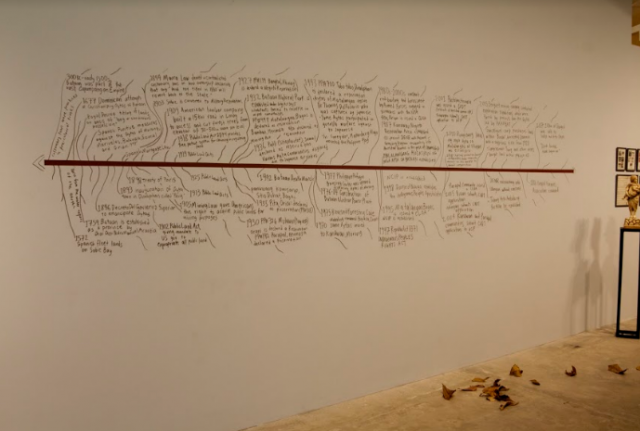

Dayrit, with input from the Aytas, retrace and amend the Bataan Ayta’s history in a timeline drawn directly on one wall where the artist added incidents of land grabbing and encroachments on ancestral homelands, as well significant Ayta moments that include the times when they marched in protest or united to form an organization.

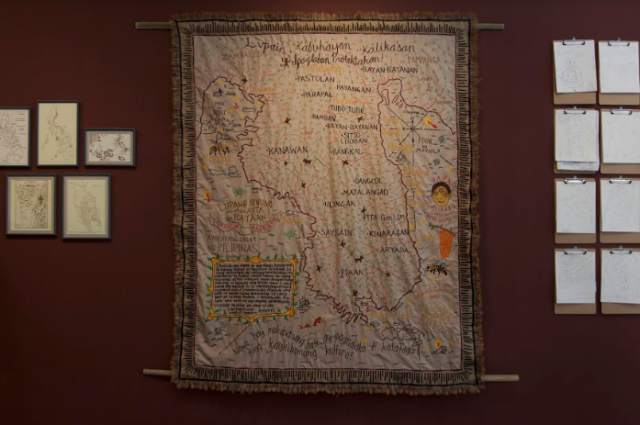

Their own notions of their domain (expressed by the Ambala and Magbukon tribes via drawings of maps gathered in clipboards) accompany and inform Dayrit’s mesmerizing tapestry, Lupang Ninuno ng mga Ayta ng Bataan.

In this totem piece, Dayrit’s artistic activism shines brightest with his manifesto embroidered on it. He hopes that the exhibition helps the Aytas' struggles and reminds the viewer that they are Filipinos too.

Dayrit also articulates an urgent need to reshape a collective consciousness eroded by displacement and the subsequent cultural and spiritual disconnection:“Yung sarili kong parang aspirations for them, is i-develop nila for themselves yung consciousness ng pagiging Ayta; yung kamalayang kulot.” — LA, GMA News

Busis Ibat Ha Kanayunan, or Voices from the Hinterlands runs up January 23, at Bellas Artes Outpost, Karrivin Alley, Don Chino Roces Avenue Extension, Makati City; bellasartesprojects.org