Being Othered at home in ‘Mabining Mandirigma’

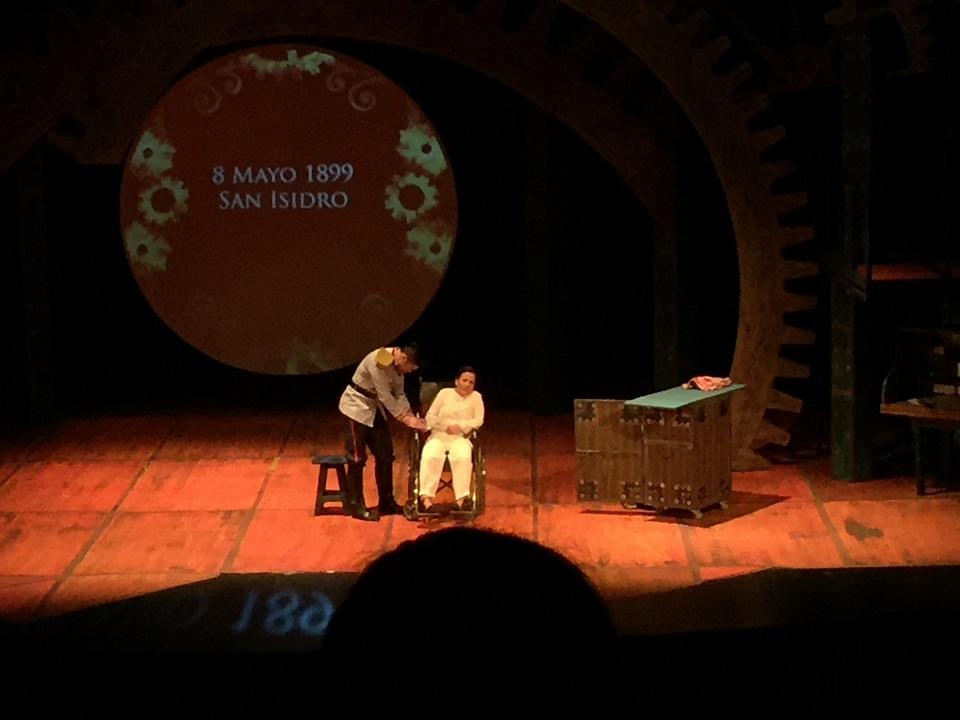

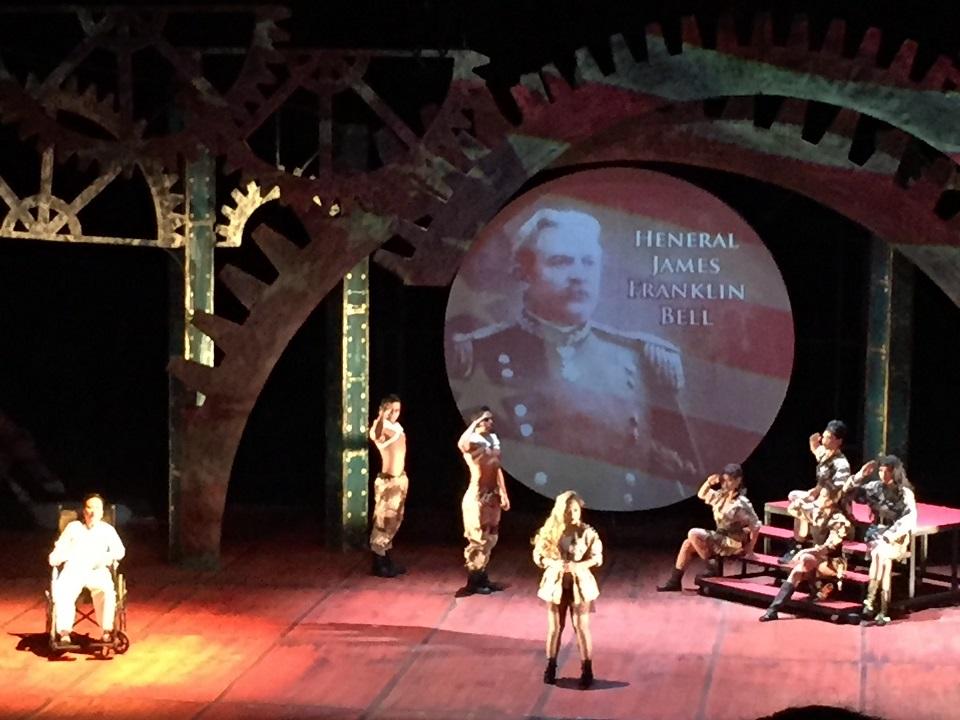

At first glance, Nicanor Tiongson's Mabining Mandirigma is a steampunk play in name only. The stage (by Toym Imao) is framed by giant cogs, a bare metal tower, and a circular screen, creating an effect of a workshop, while the costumes (by James Reyes) are influenced by the reimagined Victorian times: goggles, brass arm gauntlets, and saya-corset ensembles.

The narrative of the play itself, however, pits its titular character's creed of revolution and native culture against the genre’s message of industrialization and glorification of Western civilization.

Mabini (Liesl Batucan) himself attests to this as his clothing remains simple in contrast to the Ilustrados— bedecked in goggles, chains, and red finger lights over Spanish-style suits—and the US military, who are portrayed by women in corsets over beige shorts and helmets.

Historically, and in the play, Mabini also attempts to advise Aguinaldo (Arman Ferrer and David Ezra) against falling to both parties and his pride, both of which lead to the modernization of the Philippines in the Western sense of the word.

Sites such as Racialicious and writers like A. E. Samaan define steampunk as a glorification of the Victorian era's virtues and vices—industrialism, meritocracy and progress over equal rights and humanization—which, one can argue, won out in Philippine history.

This makes Mandirigma a historical musical in fancy dress.

However, a theory favored by Margaret Killjoy and other multiculturist proponents state that steampunk has the capability to subvert the highly oppressive, colonial trappings of its historical background.

Mabini’s struggle to continue the revolution started by Gomburza, La Liga Filipina, Jose Rizal, Andres Bonifacio, and Juan Luna amidst pernicious advisement by Pedro Paterno (JV Ibesate) and Felipe Buencamino (Jonathan Tadioan) attests to this. In a definitive moment in the play, he even fulfils the condition of using steam-and-cog-powered technology by sitting atop a metaphorical, metal-winged wheelchair.

His sense of being Othered at home by his refusal to embrace modernization, as prescribed by foreigners and elites who know nothing of the lives of ordinary Filipinos, is the closest one gets to the meta of steampunk.

In practice, however, the use of anachronistic technology is mostly used to show the inevitably insurmountable challenges Mabini faces throughout the musical.

Despite steampunk being mostly aesthetic, all the brass does make Mabini's dreary journey an enjoyable romp. It’s easy to say that Filipiniana is more ingestible in the form of a zarzuela, but Mandirigma's musical themes (by Joed Balsamo) and dance (by Denisa Reyes) compel audiences to see the absurdity and nobility of Mabini’s struggle.

Its choice to give different factions a distinctive musical style—Filipiniana vaudeville for the Ilustrados, Americana for the US military, and an almost-operatic turn for Mabini and Aguinaldo—also puts a new spin on the oft-neglected tale of the Philippine Revolution’s cerebral warrior.

And this focus by on Mabini’s intellect and integrity instead of his disability is another choice that distinguishes this musical from patriotic gushes.

Tiongson’s Mandirigma is ripe with potential. A good half of the audience during the premiere last February 19 were students and young adults. Doubtless, many of them were forced to their seats by academic, familial, or romantic requirements.

But just how many of those young ‘uns will be inspired to research the words behind the lyrics, whose words are beautifully sung but often too rapid to absorb? How many will be fascinated by the realization that, as Mabini and other revolutionaries are fighting to free the country from the negative influences of foreigners, factory workers and feminists are fighting for a better way of life in the homeland of these same foreigners?

Most will already see the significance of Mabini’s fight in the current political milieu of the Philippines, as the country prepares to pick its new president. Will their choices, like Aguinaldo, be driven by pragmatism and pride? Will they pick leaders who “privilege the oligarchy of the educated over the oligarchy of the ignorant”? Or will they, at the risk of being othered in their own communities, defy personal interests to go beyond class and regions to think and act as Filipinos, as Mabini defines it?

The cast and crew gave their two cents in the epilogue which not only serves to recap the lives of characters in the play, but to put into words subtle jibes at the current crop of Ilustrados the musical cannot verbalize.

The production itself is wonderfully put together. The stage lighting and sound design (by Katsch Catoy and TJ Ramos) informed and supported the performances of the actors and helped bring the world of late 1800’s Philippines to life. Two scenes in particular, Luna’s assassination and Mabini’s exile, mark the influence of both in congruence with the video projection design (G. A. Fallarme).

Batucan and Ferrer were, as leads, stand-outs, especially in a terrific duet near the end of act two that made use of Batucan’s firm vocals and Ferrer’s hair-raising tenor to show the tragic end of Aguinaldo and Mabini’s bountiful partnership.

As far as history lessons go, Mabining Mandirigma is a palatable and stylish effort that younger generations should pay heed to. — BM, GMA News

"Mabining Mandirigma" is currently at the Cultural Center of the Philippines' Tanghalang Aurelio Tolentino. Closing date is March 13. Tickets are available at the CCp and at Ticketworld.