Bringing back The Force: The road to the ‘Star Wars’ prequels

As “The Force Awakens” hits cinemas, I continue my retrospective series (the first part can be found here) with a look at the franchise’s direction following the release of the finale to the classic trilogy, 1983’s “Return of the Jedi.”

Released to tremendous box office, “Jedi” was an out-and-out hit, wrapping up its predecessors’ plotlines while showcasing the very best in traditional model-making, analogue compositing, hand-drawn animation, prosthetics, puppetry, and stop motion techniques. As far as Lucas and his teams were concerned, they had pushed analogue effects as far as they could go, and it would take a technological quantum leap to change the game as they had with “A New Hope” had been in 1977.

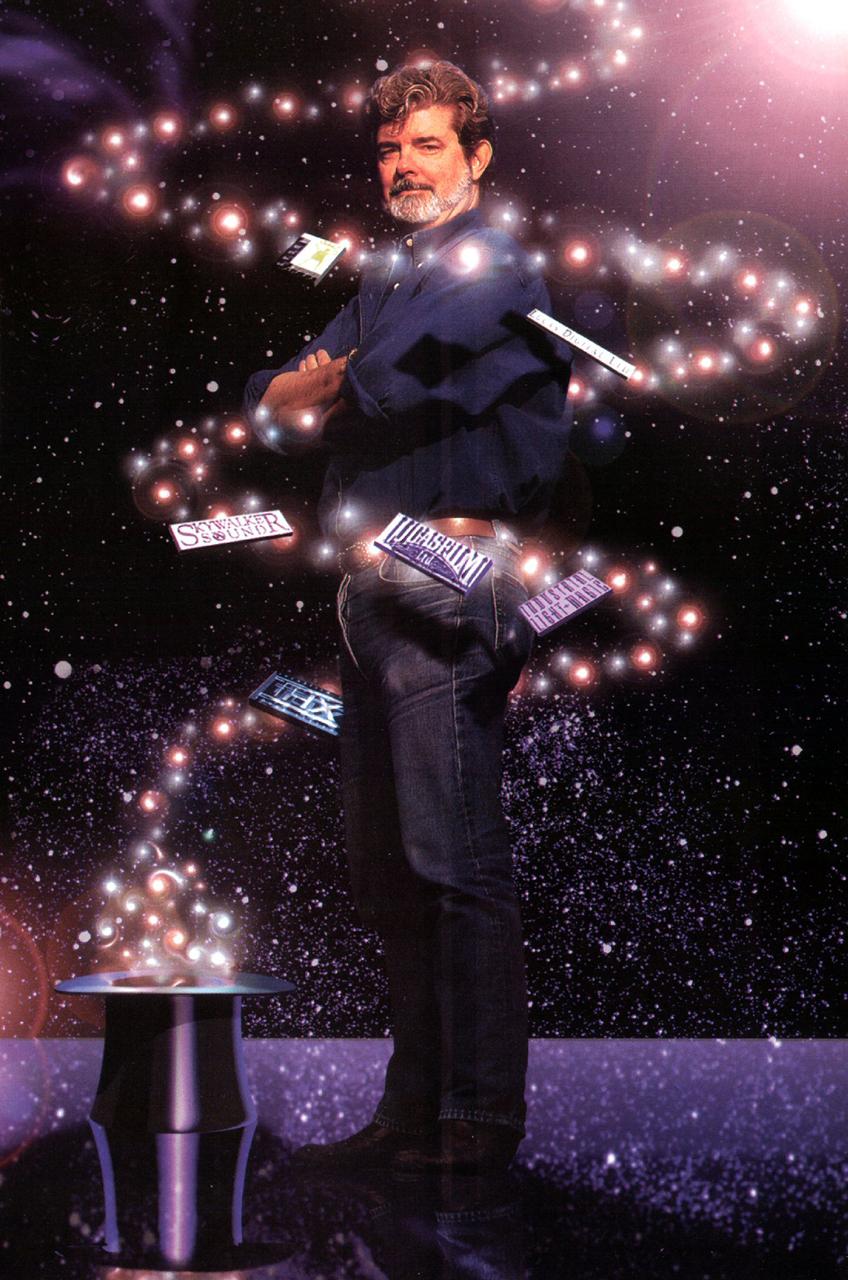

However, it wasn’t just the desire to wow audiences that was on Lucas’s mind at this point. His dissatisfaction with the state of filmmaking technology (and the traditional Hollywood studio system that he had by now largely divorced himself from) had led to him to establish numerous companies since the late 70s to aid in the creation of his “Star Wars” films. While some of them, such as visual effects powerhouse Industrial Light and Magic (of “Transformers”, “Pirates of the Caribbean”, and “The Avengers” fame), were well on their way to self-sufficiency, others, such as the division later known as Pixar (yes, that Pixar), would be sold off (to Steve Jobs, no less) as Lucas decided to concentrate on creating live-action narratives. Simply put, with no “Star Wars” films forthcoming (for the foreseeable future), Lucas realized he would need to widen his horizons if his companies were to survive.

Thus, the 1980s saw Lucas expanding his companies’ client base beyond “Star Wars”—and, in the process, breaking ground in nearly every aspect of media creation over the next two decades. Aside from the aforementioned ILM (visual effects for film) and Pixar (purely computer-generated imagery, or CGI), Lucas’s companies made pioneering strides in standardized audio and visual formats for cinemas and home theaters (THX), sound design and recording (18-time Oscar-winner Skywalker Sound), computer gaming (LucasArts), and even introduced the now-standard video timeline through ILM’s in-house non-linear digital editing system (EditDroid, which was sold to Avid). Such was the caliber of talent that Lucas cultivated that, in 1987, an ILM employee named John Knoll (who would later oversee visual effects for the “Star Wars” prequels and “Mission: Impossible” movies) co-created Photoshop with his brother, Thomas, in their spare time because they wanted an affordable way of manipulating images.

As Lucas forged ahead in his quest to reshape the industry whose conditions had given him a heart attack during production of “A New Hope”, events were transpiring that would put him back in the director’s chair he had walked away from all those years ago.

In 1992, with principal photography completed on “Jurassic Park,” director Steven Spielberg asked his old friend Lucas to assist in overseeing post-production on the (now-classic) dinosaur thriller. As ILM churned out (then-) cutting-edge CGI to bring the prehistoric beasts back to life, Lucas realized that the technology he’d spearheaded the creation of in the late 1970s had finally caught up to his imagination – now, freed from practical constraints, literally anything he dreamed up could be rendered and put on the big screen.

This wasn’t to say that Lucas hadn’t been aware of the state of the art before that point. Prior to the release of “Jurassic Park”, ILM had already been experimenting on TV’s “Young Indiana Jones Chronicles”, honing their techniques for creating digital doubles (for dangerous stunts), virtual crowds (for when the budget wouldn’t allow more than a few extras), set extensions and background replacement (for overcoming the practicalities of physical sets and locations). Building on their successes from “Jurassic Park” (photorealistic animals), “Terminator 2: Judgment Day” (photorealistic textures, reflective surfaces, and morphing) and, in 1995, “Casper” (first-ever fully expressive photoreal CGI animated character), the next revolution in big screen visual effects was well and truly under way.

The proofs of concept would come in the forms of the very movies that had made Lucas’ name: the classic “Star Wars” Trilogy. Lucas had decided to commemorate “A New Hope”’s 20th anniversary by re-releasing the original trilogy on the big screen for the first time since the latter was re-released in 1985. Dubbed “The Star Wars Trilogy: Special Edition”, the three classic films received Lucas-approved restorations, created by scanning each film’s negatives into a computer and painstakingly cleaning them of dirt, fingerprints, and scratches, one frame at a time.

If the alterations had stopped there, it is entirely possible that the “Special Editions” would be far less divisive (but probably not). Making the films sharper and more detailed through restoration, digital color correction, and removal of visual artifacts and distortions (left by analogue compositing techniques) was one thing, but Lucas went a step further by adding in previously deleted footage (resulting in redundant portions), altering lines of dialogue (changing the context of entire scenes), revamping the sound mix (with varied results), and, most infamously, replacing much of the Academy Award-winning model work with CGI.

While purists were quick to cry foul, it was impossible to deny that many of those who turned out to see the “Special Editions” were more than happy for the chance to experience “Star Wars” in cinemas, regardless of the context. After all, since “Return of the Jedi’s” 1983 bow, fans’ only outlets (aside from home video) had been a pair of cheaply animated cartoons (“Droids” and “Ewoks”), and two direct-to-television live action films (“The Ewok Adventure” and “Battle for Endor”) of middling quality. By 1985, with no new films to support, even the venerable “Star Wars” action figures were forced to cease production. While the early 90s had seen Lucas dip into the fandom with numerous video games and authorized novels (many of which were bestsellers), the “Special Editions” were what truly validated his franchise’s drawing power. The series was a blockbuster once more, and now, their appetite whetted, audiences were ready for more.

"Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace" was released to great fanfare in 1999, following over a year of anticipation, fuelled in no small part by a masterful marketing campaign built around the idea of every story having a beginning.

Since the few snippets teased throughout the classic trilogy, people had wondered about the path that led Anakin Skywalker to the Dark Side. Portrayed by 9-year-old Jake Lloyd, audiences were introduced to Anakin as a slave boy with aspirations of greatness. A chance encounter with Jedi Knights Qui-Gon Jinn and Obi-Wan Kenobi (Liam Neeson and Ewan McGregor) will give Anakin the chance he’s been hoping for. We are also introduced to Queen Amidala (Natalie Portman), the ruler of a peaceful planet in the middle of a trade conflict with the potential to erupt into full-blown war.

_as_R2-D2_looks_on_2015_12_17_16_02_47.jpg)

“The Phantom Menace” set records even before it was released, as the official “Star Wars” website crashed from the sheer amount of traffic from people trying to view the film’s first trailer. At the same time, fans were flocking to theaters, paying full price for “Death Takes a Holiday” remake “Meet Joe Black” in order to view the trailer that played before the main feature, then leaving before the film even started.

“Episode II: Attack of the Clones” continued the story with Anakin (now played by Hayden Christensen) as a temperamental young Jedi under the tutelage of Obi-Wan. He is assigned to protect his beloved Amidala from assassination as Obi-Wan’s look into the attempts on her life put him on the trail of a galactic conspiracy.

Bogged down by stilted acting and awkward dialogue, “Attack of the Clones” is by far the weakest of the first six “Star Wars” films. As Anakin, Christensen is nowhere near gifted enough to convey the range of emotion his character is required to convince us of his gradual descent into darkness, while the overreliance on CGI gives the production an overly-processed, artificial look that, far too often, is indistinguishable from a video game.

“Episode III: Revenge of the Sith” finally delivered on the promise of the prequels to show us just what would turn a promising young Jedi from the path of right and virtue to becoming the series’ embodiment of evil.

With narrative touchpoints that tied the story directly to those of the classic films, a scenery-chewing performance from Ian McDarmid as Chancellor-turned-Emperor Palpatine, and the lightsaber battle to end all lightsaber battles, “Revenge of the Sith” brought the series full circle and, in many ways, redeemed the two films that came before it.

While “Sith” ended on a high note, it was impossible to ignore that nearly every emotional beat it hit stemmed from its connections to twenty-year-old movies, as opposed to anything Episodes I and II had set up. And while this wasn’t necessarily a bad thing, one wonders why we had to suffer through two prior films to get to that point. As the ostensible foundations of a beloved story, the prequel trilogy failed to satisfy. However, as technical exercises into what a filmmaker in full control of everything that appeared onscreen, they were wonders to behold.

Perhaps the greatest contribution the prequels made to the overall mythos was their serving as a gateway to many a current fan into a franchise that was already known and loved by millions. Simply put, there is no wrong way to enjoy the “Star Wars” saga, and certainly no wrong place to begin.

Now, as “The Force Awakens” looks set to take over every cinema in the world, there’s never been a better time to catch up and dive into the galaxy that George Lucas built. — BM, GMA News

“The Force Awakens” is now showing in cinemas.