Monkey Business and the emergence of new Japanese writing

Before we begin, let’s talk about the elephant in the room. Or, perhaps we should say, the vanishing elephant, to paraphrase one of his earlier stories.

Haruki Murakami, avid long distance runner and erstwhile agony uncle, is quite possibly Japan’s most prominent contemporary literature export. Murakami’s work has been translated in fifty languages, has sold in the millions, and is a perennial bettors’ favorite for the Nobel Prize for Literature.

And all for good reason. Prior to Murakami’s popularity, Japanese literature was represented overseas by such stalwarts as Nobel laureates Kenzaburo Oe and Yasunari Kawabata, as well as Yukio Mishima. Their works reflected Japan society’s struggle with modernity, and fuelled foreign audience’s fascination with the exotic East. Murakami, a self-proclaimed literary “loner”, was something of an outsider: influenced by jazz music and Western literary traditions, his works were introspective, often comically surreal, and with no pretensions to representing anyone or anything beyond Murakami’s own worldview.

Once shunned by the establishment, Murakami is now a pre-eminent man of letters, the reading public’s acceptance of his quirky style giving the current generation of writers the freedom to experiment with their own ways of seeing. These are the writers featured in Monkey Business, whose editor Ronald Kelts and contributing artist Satoshi Kitamura headlined a Japan Foundation Manila talk on New Japanese Writing at the Ayala Museum.

Simian says Monkey Business was founded in 2008 by Motoyuki Shibata, arguably the most renowned translator of American literature into Japanese. What was conceived as a thrice-yearly Japanese language anthology of contemporary Japanese and American writing in translation soon evolved into an annual English language collection, with the help of co-founder Ted Goossen, best known as Murakami’s current translator.

Monkey Business was founded in 2008 by Motoyuki Shibata, arguably the most renowned translator of American literature into Japanese. What was conceived as a thrice-yearly Japanese language anthology of contemporary Japanese and American writing in translation soon evolved into an annual English language collection, with the help of co-founder Ted Goossen, best known as Murakami’s current translator.

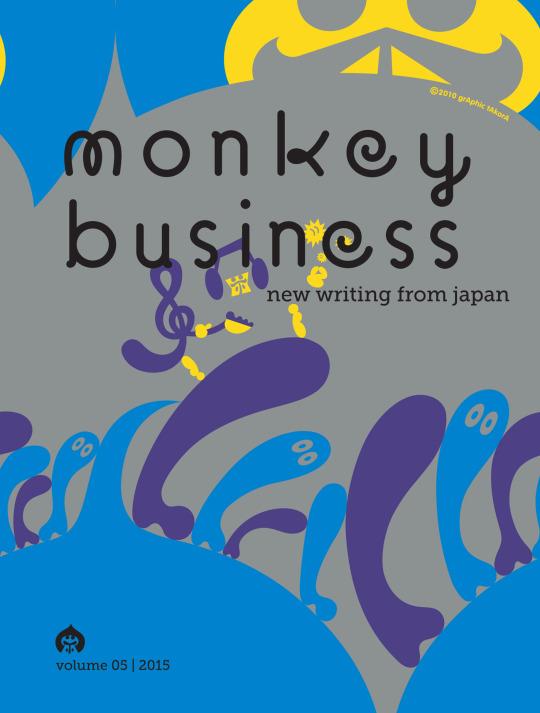

Early this year, Monkey Business launched its fifth issue, featuring, among others, previously untranslated fiction by Toh EnJoe, Mieko Kawakami, and Stuart Dybek; comics and graphic narratives by Kitamura and Ben Katchor; and essays by Kelly Link and, yes, Uncle Haruki himself.

“Monkey Business was derived from the title of a Chuck Berry song [Too Much Monkey Business], which captures Shibata-sensei’s idea of literature as fun and inventive, liberated from the cares of real life,” explained Kelts, when asked by a participant if the title had anything to do with corruption.

While the journal title is certainly no reference to any sort of illegal activity, its editorial guidelines can be viewed as decidedly anti-establishment. The literary establishment, that is. Shibata’s only criteria for publication is whether he likes a piece or not. “We just publish what we love. If you love something, chances are somebody else in the world will love it too.”

One of Shibata’s inspirations for founding Monkey Business was the American independent publishing industry, which Kelts noted, published work that may not have a large audience, but engage very passionate readers.

Monkey Business’s editorial freedom is supported by generous partnerships from the Brooklyn-based publisher A Public Space and Nippon Foundation. Networking also plays an important role in putting the magazine together: Shibata solicits pieces from writers he’s worked with or translated and before, and when the latest issue is published, the team go on a launch tour of New York and other key cities in the United States; this year, they also visited Jakarta, Manila (apart from the talk, they joined a panel on graphic literature at the Asia Pacific Writers Conference), and Singapore.

Blurred lines

Asked to describe new Japanese writing—the sort highlighted by Monkey Business—Kelts remarked, “[Japanese writers] move between fantasy and reality very smoothly,” a tendency perhaps made more prominent by the easy shifting between online and offline worlds.

That being said, familiarity and acceptance of new technology is not the driving force behind the surreal and fantastic world of contemporary Japanese writing, but a centuries-old tradition. When a participant wondered why Japanese authors write the way they do, Kitamura replied, “I’m not sure I can be objective about this question. I feel like [this kind of writing] comes naturally.” He mentions that one of their traditional tales, The Bamboo Princess, contains elements of science fiction: in the end, the princess in question is fetched by a space ship and brought to her real home, the moon.

A more academic view, according to Kelts, is that Japanese literature is shaped by their Shinto tradition, which can be simplistically defined as an animistic spirituality. “Even inanimate objects can have a spirit within,” he noted. “[Take, for example], the works of Hayao Miyazaki, where even the smallest blade of grass is imbued with life.”

In addition to changing writing style, Japanese literature is seeing an emergence of women writers, tackling changing social mores. ““Women in Japan are undergoing a radical transformation—they are entering the workforce, making more money, not getting married— and this is chronicled in their work. There are a lot of very talented women writers and artists in Japan.” Monkey Business counts among its regular contributors Yoko Ogawa (translated novels include The Housekeeper and The Professor, Hotel Iris); Tomoka Shibasaki (last year’s Akutagawa prize winner for Haru no Niwa/Spring Garden); and singer turned writer Mieko Kawakami, whose fiction has been translated in Korean, German, and Chinese, but sparely in English.

An ear for language

While most Japanese contributors to Monkey Business write in Japanese and have their works translated, Kitamura’s graphic narrative adaptation of Charles Simic’s poem “Doubles” is written in English. The artist spent decades living in the United Kingdom, where he began his career as an illustrator and author of children’s books. “When I moved to the UK in my early 20s, I did not know how to speak [English],” he recalled. “Learning it as if I were a child, made me more conscious of the language.” His contribution to issue 5 of Monkey Business, “Variation”, manifests a deliberate, spare approach to language that mirrors Simic’s original text—Kitamura’s narrator is a stranger observing Simic’s protagonist—and gels neatly with his monochrome pen-and-ink illustrations.

Speaking of his experience at the other end of the translation process, Kelts reiterated the importance for translators to be excellent writers who love the original material (and, therefore, be willing to devote time, energy, and creativity to the project). ““I often try to appreciate the way they tell the story [in ways] that cannot be told by, for instance, an American.” He also noted the growing market for literatures in translation—the appreciation for local cultural being a natural offshoot of globalization—citing Amazon’s recent $10-million investment on a new translation program as an indicator that translated works will be made more accessible and, as a consequence, more popular.

Old media made new

The short talk ended with Kitamura presenting two graphic narratives—one for adults and another for children—in kamishibai, or stortytelling via images presented in a paper theater. Kamishibai as street performance waned in the 1950s and 60s, following the rise of the television, thus prompting its practitioners to ply their trade in manga and anime.

Kitamura’s performance was a resounding hit with the audience—many participants marveled at the ingenious theater construction and its potential to tell new stories—a fitting reminder that a culture’s narrative will find an eager audience for as long as there are platforms like Monkey Business to showcase it in its best possible form. — BM, GMA News