Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Saving the ‘world’: Keeping indigenous culture alive at ‘Woven Universes’ exhibit

Text and photos by VIDA CRUZ, GMA News

Four samples of the Saputangan, a Yakan headcloth, at the 'Woven Universes' exhibit

Curator Floy Quintos, who owns the cloth samples and put the talks together, explained that he started collecting these because “they were there and they were affordable.” His source is a Kalinga woman who happens to sell him valuable pieces from time to time.

“Each piece represents the universe on its own,” he said of the collection. Of the very rare Isinay ikat blanket, he said that it had been found in the previous owner's baul—the owner had turned Christian and was unable to use it.

In a series of talks at Yuchengco Museum Saturday, experts and scholars managed to connect math, textile conservation, and a very rare shroud.

Perfect symmetries

An albong, a Bagobo or B'laan woman's blouse

These symmetries were achieved by weaving simplified figures from nature and cultural folklore and mythologies, or else rotated, translated or reflected combinations of circles, squares, and triangles.

“What these precise patterns show is that there is a lot of inherent mathematical genius in the weavers,” said Garciano. “There is a lot of soundness in what they have done. They may not even have thought about the mathematics of the weave.”

Keeping time and rot away

The second talk, delivered by textile conservationist Marilou Dancel of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, was all about how to preserve textiles from deterioration, be they indigenous woven cloth or Spanish-era clothing (the example she gave was the vest of Jose Rizal).

“Conservators must respect the aesthetic, historical significance, and physical identity of the object,” said Dancel. She also recommended the use of cotton gloves when handling textiles.

Dancel noted that treatments should be reversible, if possible. If the social functions of the object help its uses deteriorate in the way frequently wearing a t-shirt will make it loose and fade the color, only then may the conservator commission a reproduction.

A traditional backstrap loom

She had some tips for displaying and storing the cloths, too:

- Eliminate light sources with blinds or curtains and keep the material as far away from bulbs as possible.

- Small flat fabrics must lie flat on acidic boards or Japanese paper. Large fabrics can be folded to fit in a box.

- Remove unwanted staples to prevent rust stains and cover metal accessories with acid-free paper.

- Store in cupboards with doors or enclose in curtains made of muslin and cotton. One can also hang the textiles in open storage areas provided the textiles are draped over with cotton.

'Queen of all shrouds'

UP Baguio anthropology professor Analyn Salvador-Amores discussed a living sample in her talk: the Isinay traveling ikat blanket, called “ues pinutuan,” which Amores described as the “queen of all funerary blankets.” This made the Isinay, at present an endangered people, the most sought-after weavers in the Northern Luzon area, as these were used by the affluent of different tribes to wrap their dead in.

Even in 1903, the blanket was very expensive, often costing six silver coins or one carabao to trade. These days, it costs around P8,000. This is partially because of the way the blanket “travels” as it is made—the cotton threads are from Cervantes, Ilocos Sur; the cloth is dyed in Pangasinan; woven in Nueva Vizcaya; traded in Benguet. The Isinay intermarry and migrate to Ifugao and other regions; new blankets are woven in Mt. Province, and then sold in Baguio City.

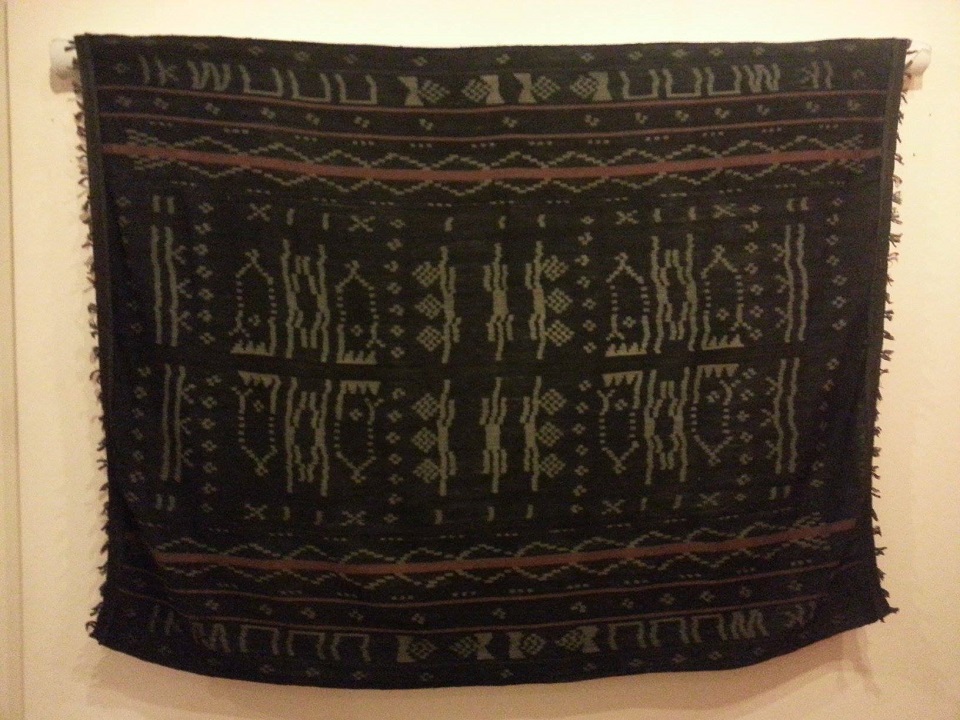

The Ues Pinutuan, or the Isinay Traveling Ikat Blanket

The art of weaving the blanket used to be passed down only among the widows of the Isinay tribe in Nueva Vizcaya, making it a very secretive art indeed. Amores pointed out that the widows weave their signatures in some corner of the blanket.

“Only widows can weave the blanket,” said Amores. “And they can only weave it at night. The Isinay have a lot of sayings and beliefs about the blanket, such as not showing it to the children.”

Amores shared how she went to visit one of the Isinay elders in order to have him read two sample blankets. He told her that if she opened the blanket in the house, it would attract the ancestors and they would have to slaughter three carabaos.

The last authentically Isinay blanket was woven in 1978, and is currently on display at the Church of St. Vincent in Dupax del Sur, Nueva Vizcaya.

“I've been to see that blanket three times,” said Amores. “Before, that blanket used to hang around without anyone knowing what it was or what its significance was.”

“The day before my third visit, the caretaker told me that they washed the blanket with chlorox, as it was so dirty,” Amores added, prompting horrified gasps from the audience.

A pair of sawal, a Bagobo or B'laan man's trousers

These days, the Isinay—all 2,000 of them—are trying to reclaim their culturea and their ancestral lands. One way to do that is through the ues pinutuan, which helps establish that they had a complex society.

The symbols that once decorate the blanket have changed over time with the onset of Christianity and copying by modern weavers. Inevitably, artists from cities far and away will want to copy and modify the designs, too. How can they do that while paying respect to the culture where it originated?

Amores answered that the result is a double-edged sword: reving the culture and changing its meanings. She answered, “Always make it a point to do extensive research and give respect to the community. What we need more right now is extensive documentation of what's left of their culture.” — BM, GMA News

"Woven Universes" at Yuchengco Museum runs until Feb. 28.

More Videos

Most Popular