ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Exhibit on Filipino churches hopes to teach young Spaniards about PHL history, culture

Text and photos by REGINA LAYUG-ROSERO

Churches used to be the place where you went for refuge in times of great need, where you celebrated new life, mourned those that had passed, sought answers, made offerings. While faith and prayer are very personal, even private, the appreciation of churches—both the physical structures and the social entity—can be academic, artistic, and even touristy. Many tour guides and travel agencies offer church tours, while some of the oldest churches in the world have their own museums, featuring the history of the building, the parish, special saints, or the religious order that built it. These days, churches are temples not only of faith, but also of art, architecture, history and culture.

The Ortigas Foundation's John Silva

In a recent lecture for the Museum Volunteers of the Philippines, Silva spoke not just of churches, but of the Church, her history in these islands from the arrival of the conquistadores to the recent shake-ups by the radical Pope Francis, and her role in the lives of Filipinos throughout the centuries.

From book to exhibit

The lecture was a preview to an exhibit Silva is curating, “Churches of the Philippines: Lasting Links to Spain,” opening in Madrid’s Casa de América in November.

Ten gallery walls will be filled with 19th-century artifacts, as well as photos of Philippine churches taken at different points in history, and Silva shared some of these photos during the lecture. The photos included the Baguio Cathedral in the 1950s, churches destroyed during the bombing of Manila in World War II, churches reduced to rubble after the 2013 earthquake in Bohol: side-by-side comparisons of photos taken decades apart.

The exhibit was inspired by the Ortigas Foundation’s documentation of churches around the Philippines. After the 1990 Luzon earthquake, philanthropist Rafael Ortigas lamented the destruction and deterioration of church buildings, and embarked on a mission to preserve them, at least in photographs. The Ortigas Foundation continued the decades-long documentation project, and published the photos in “La Casa de Dios: The Legacy of Filipino Hispanic Churches in the Philippines1” in 2010. Since the book’s publication, the foundation and the Philippine Embassy in Spain worked together to mount an exhibit around the photographs.

Shared history, kinship

But why would Spaniards today care to learn about churches in a colony they gave up over a hundred years ago?

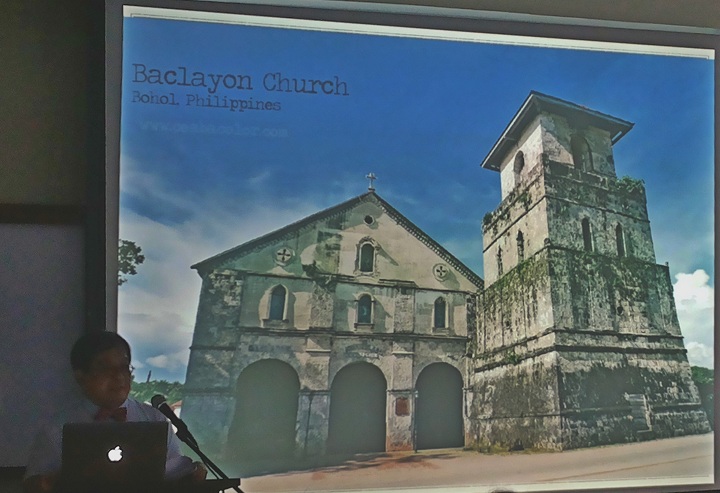

Silva shows an image of the the Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception Church in Baclayon, Bohol, taken before the 2013 earthquake.

He shared a story from his youth, of his first trip to Spain in 1975. On the train to Granada, a friendly Spanish couple made his acquaintance and shared with him their food and wine. When they found out that he was Filipino, they cheered and embraced him like a long-lost brother. They had elders who had been born in the Philippines, they said; they still had family there.

There was “incredible intimacy and connection,” Silva reminisced. “I don’t think that will happen now, because that generation is gone.”

Now, most Spaniards are unaware that their legacy is slowly slipping away. Said Silva, “Our Spanish counterparts don’t know about the destruction of heritage sites in the Philippines.”

From spices to parishes

In this story, the narrative started not with the friars who arrived with the conquistadores, but with the adventurers who colonized the Americas. The Spanish colonizers in the West Indies enslaved and brutalized the native population, to the horror of Dominican friar Bartolome de Las Casas.

Las Casas pleaded with King Ferdinand to stop the violence, and received support not only from Ferdinand, but also from Emperor Charles V and Pope Paul III. Thanks to Las Casas, commands governing expeditions to new lands now bore several footnotes: don’t mistreat the natives; evangelize them of their own free will; and don’t enslave them, because slaves can be imported from Africa.

And so the next expeditions included friars from various religious orders. “The friars were the moderating element, befriending the natives, learning the native language, making dictionaries,” shared Silva.

He believes that the many churches scattered all over the archipelago couldn’t possibly have all been built with slave labor. Most likely “the friars’ appeal to build churches became palatable” because of their early harmonious relationship with the natives; so palatable that 900 parishes had been established by the end of 19th century. But history tells us how that relationship deteriorated over time, leading Rizal and other ilustrados to decry Church abuses later on, and revolutionaries to rise up in arms.

From heritage sites to ruins

Baclayon Church's facade and belfry lie in ruins in this photo taken October 17, 2013, two days after the magnitude-7.2 earthquake that damaged or destroyed several of Bohol's colonial churches. Mariz Umali

Regardless of location, any church can be leveled during an earthquake or a fire. Should a structure survive those phenomena, inevitably it will fall into disrepair anyway.

With each church that suffers damage of any sort, Silva could only ask, “How do you rebuild? Will you restore it to its original form? Restore the façade only? Or build a completely new church?” Each option would cost millions of pesos, and take years to complete.

He cited the example of the church of La Purisima Concepción in Guiuan, Samar, where Typhoon Yolanda first made landfall last year. The roof was ripped off, the ancient tile floors flooded. “It’s one of our poorest provinces; where will they get the resources to rebuild this?” Silva enumerated many other small towns and their churches in desperate need of restoration: Paoay church; the San Sebastian Church near Quiapo; Tumauini, Isabela; Baclayon Church in Bohol.

Perhaps the exhibit in Madrid will rekindle a love of Philippine churches in the Spaniards, and they can help restore the churches their ancestors and ours built. Perhaps Silva’s story will bring a new generation of Spaniards to these shores, and restore that early relationship between our two cultures. — BM, GMA News

The exhibit “Lasting Links with Spain: The Churches of the Philippines” will be held in Casa de América, Plaza de la Cibeles, Madrid, Spain, from November 28, 2014, to February 18, 2015.

More Videos

Most Popular