ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Celebrating Constancio Bernardo, foremost abstract artist of the Philippines

By FILIPINA LIPPI

Constancio Bernardo's Wild Flower Series II, 1977

“We hope to build a facility where students and scholars can appreciate my father’s artistic range and versatility. Many art works in this collection have never been exhibited in his lifetime,” older son Angelo, head of the Museo Bernardo Foundation, told GMA News Online.

Each of the paintings, sketches, and memorabilia has been identified – guided by the comprehensive Bernardo Catalogue Raisonne that Angelo, an anthropologist, undertook from 1999 to 2001, with a grant from the Ayala Foundation. ”My father was consulted on the provenance and context of each of his works,” he said.

In the collection are Bernardo’s realistic art works inspired by impressionist Fernando Amorsolo, his mentor at the University of the Philippines from 1934 to 1948; studies in the Italian Renaissance style of painting from 1948 to 1949, done during his first two years as a Fulbright scholar at Yale; and several representational pieces.

The collection’s gems are abstract pieces that Bernardo started creating—already as a master—at 37 in 1950 after he was influenced by artist Josef Albers, then head of Yale’s painting department.

The artist in front of Perpetual Motion (Opus No 1), done in the US in 1950 and exhibited in a show-cum-thesis defense at Yale in May 1952.

Motion is Bernardo’s answer to the philosophical problem tackled by abstract expressionists’ search for pure painting, or pursuit of the non-objective world with colors and lines (which, by themselves, are also objects). “My father finished Perpetual Motion in 1950 – but did not include it in the works that he exhibited in Yale’s Annual Student Exhibitions in 1950 (when he received the school’s Most Advance Showing prize) and in 1951. He unveiled Perpetual Motion for the first time when he defended his Masters’ thesis at Yale in 1952,” said Angelo.

Guided, since then, by his discovery of motion as a viable theme to evade lines and shapes becoming recognizable images, Bernardo also fastidiously mixed colors to create visual haikus that intentionally burst with subtle hues to surpass the outlines of geometric shapes and make them less recognizable. This way, his canvases are layered with subtle symphonic colors – just like the echoing silences in the impressionistic music of Debussy and Ravel, or the minimalist ballade of Satie.

Abstract art shaped by music

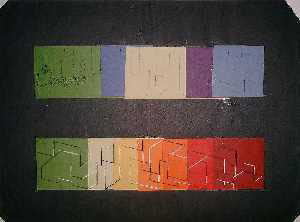

Part of Perpetual Motion studies (1950)

Instead, he thrived in the milieu of conflict and contrasts that enveloped him when he reached the US. When he left Obando—his sleepy hometown in Bulacan—the Philippines was still rising from the ashes of World War II and the ravages of hundreds of years of Spanish and American colonialism.

Even the cultural ferment of realism and abstraction at Yale gave him both a sense of discipline and freedom. At home in the disturbing philosophical and scientific movements that he read about and discussed at school, “philosophy and art history became his favorite subjects,” said Angelo.

Bernardo’s strength in taming of conflicts came from music, the soul of his inner spheres.

“He played the piano [in] UP. He was the UP Reserve Officers’ Training Corp Band’s trumpet player. He studied violin at Yale. He read scores, made musical arrangements. He would sing, hum, and whistle while at work in his studio at UP’s Area II and later at UP Village. In old age, he taught himself guitar and electric organ playing,” said Angelo. “Many titles of his art works allude to music.”

A globally important abstract artist

Bernardo in later years

Turning point

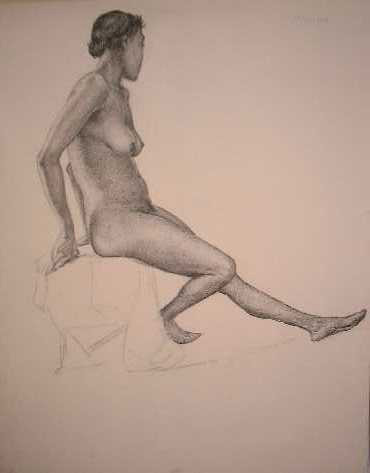

Figure drawing by Bernardo at Yale in 1948

Also mentioned were Bernardo’s other modernist mentors and influences at Yale: Wilhelm De Kooning (who “went to his classes in clogs”); Pennsylvania-born Franz Kline, whose black and white calligraphic works were originally sketches made on telephone books; and Washington-born Robert Motherwell, “abstract expressionist’s philosophical spokesman.”

“They did not insist anything except [for us] to be free. Walang ginigiit kundi maging libre kami [in art exploration],” Angelo recalled his father as saying.

Bernardo was also exposed to other European abstract painters who came ahead of Albers in the US, such as Russian Jew Mark Rothko, Armenia-born Arshile Gorky, and German Hans Hoffman. Bernardo also admitted to poet Ricaredo Demetillo in 1956 one major influence: Dutch Piet Mondrian, who painted “motion” by rolling on a canvas on the floor—with paint on his body.

Dragon years in Manila

As expected, when he returned to Manila in December 1952, Bernardo was rejected by Amorsolo, his superior at UP. His works were not set apart as seminal to the Philippines’ postmodernist period despite the establishment of the 13 Moderns, an anti-Amorsolo group that deliberately engaged in semi-abstract figurative forms.

Bernardo persevered in doing abstract art even if the style was derided as “art for art’s sake” by young, historically and socially conscious artists who launched the social realism movement of the 1970s. He taught art history in UP, but never insisted on his true place and value in the development of Philippine abstract art.

“His modesty and humility worked against him," said Angelo, whose unpublished eight-volume biography of his father, done from 2009 to 2012, will make a long overdue rectification – and give the country’s globally foremost abstract painter the accolade that he richly deserves. — BM, GMA News

Photos courtesy of Angelo Bernardo

More Videos

Most Popular