ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Dukit: Celebrating and preserving culture in the Woodcarving Capital of the PHL

Text and Photos by RUSTON BANAL

The barrio of Sta. Ursula in Betis is the origin place of “dukit” (woodcarving). Its narrow road was once a haven for carved religious figures and furniture. But now, most woodworking shop along said road has been replaced either by a sari-sari store or car garage.

A mandukit smiles at a piece he completed during his lunch breaks.

“You can now see the scarcity of talyeris (workshop that is usually in front of every house) since the new generations of today prefer a professional job that can be attained by finishing a college degree rather than becoming a woodcarver's apprentice,” said Willy Layug, a renowned ecclesiastical sculptor and an advocate in preserving the dukit tradition.

Alongside the few remaining “matecanan mandukit” (master sculptor), Layug has been in a constant battle against the total banishment of the art, even creating a guild to introduce a program of new techniques and machines adaptable to the global market.

They even created an annual festival that commemorates the contribution of the woodcarvers which he called the Dukit Festival.

To augment the advocacy, a full-length movie feature called “Dukit,” produced by a fellow Kapampangan director Brillante Mendoza and directed by highly-acclaimed screenplay writer Armando Lao, was entered in the 2013 New Wave Category of the Metro Manila Film Festival.

Tracing 'Dukit's' roots

The dukit tradition in Betis is as old as the town itself, which was one of the earliest Spanish-era settlements. It gained an international reputation during presidency of Diosdado Macapagal, when overseas trade of carved furniture was at its peak. It was also master sculptor Juan Flores, winner of the Grand Prize in Richard Nixon’s Bust Sculpture-Making Competition in 1972, who introduced the cultural renaissance of the woodcarving tradition in the first quarter of the 20th century.

But even before the arrival of the Spanish colonizers, according to local historian Mariano Henson, Betis people were well-known blacksmiths, carvers, ship builders, and carpenters. According to “The Philippine Islands” by Emma Helen Blaire published in 1911, the riverside of Betis was even then populated by Muslims, who introduced a developed culture and way of life. “Dukit” could have been derived from their “okir” tradition.

Being an encomienda—which is what Betis was in the 1770's—meant becoming a melting pot of all things Asian and European. It was in encomiendas where the latest fads in Europe were introduced, regardless of native adaptability. In the case of the Betis people, they easily embraced what spoke to their aesthetic sensibilities and pre-colonial skills: woodcarving.

Fiesta nang Apung Tiago and the Dukit Festival

Betis boasts of the embellished interior of the magnificent baroque St. James Parish Church because of its ornate “trompe l'oeil” effect, done by local painters and with subjects derived from the Bible.

A band playing before La Torre.

A reflection of faith and their art, the church was declared a National Cultural Treasure in 2009 by the National Museum.

During the feast of Apung Tiago on December 28 to 30, seven or eight marching bands alternately play their best symphony at 10 a.m. in front of the church campanile—which is called La Tore (The Tower)—to pay tribute to the Virgin Mary. At night, these bands would then play their opus for the event called Serenata.

In tandem with this is the Dukit Festival, begun by dancers in costumes with woodcarving motifs. Roughly on its fourth year, the festival is a competition among woodcarvers in Betis, aiming to inspire the younger generation with the beauty of the art and its contribution to the material culture that defined the Betis community. It is usually held within the church's compound, entertaining church goers and visitors from out of town.

“Yearly, I join the competition not just because of the rewards and big prize money the winners can get,” stated Michael Blanco, a mid 30's woodcarver from Sta. Ursula. “But also to show to the young generations that there are still mandukit who retain the old traditions and culture of Betis.”

“We can think of anything that would help preserve this culture. But come to think of it, changes are inevitable,” said Layug. “You see teenagers and kids attached to their android phones and tablet PCs, investing much of their time on social networking sites. The world where I lived before is not the world where our youth live their idealism these days.”

“We can only think of preserving the Dukit tradition and culture. But we don't have a control on how the new generation see Dukit. It is still in their hands,” he added.

'Dukit' the film

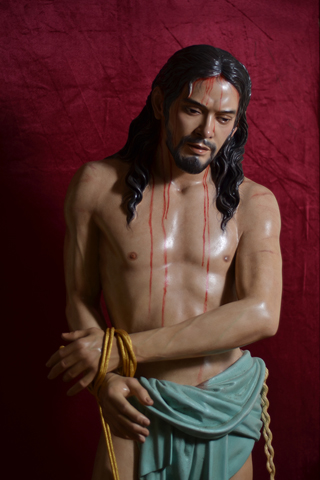

A cautivo used in the film.

Shot entirely in Betis with the vanishing wood carving tradition as the backdrop, the story was culled from sculptor Willy Layug's life as a peg.

“Dukit” began with the idea of creating a short film that illustrates a biographical sequence of a woodcarver in Betis. A group of young filmmakers in Pampanga got acquainted with fellow Kapampangan director Brillante Mendoza, who introduced them to his mentor Armando Lao, who at that time was giving film workshops and looking for possible stories in the region.

“Dukit” is Armando Lao's attempt to make an authentic regional film featuring everything Kapampangan—chief among these are language, religion, music and the dukit tradition. Except for one actor, the cast is made up of only Kapampangan talents; similarly, half of the production team is composed of young Kapampangan filmmakers. The film adopts the ‘found time’ school of shooting, using multiple cameras, improvised dialogues, and actual religious, secular, and occupational events as part of the film’s dramaturgy.

The film, however, encountered financial struggles. The initial production cost was supplemented by actor-producer Willy Layug himself. But as the making of the film progressed, larger funding was needed to supplement the cost of production.

Line producer Ruston Banal stated that he tried to look for funding by writing letters to government officials, private sectors, clubs, and organization asking for support to augment the production. None of the 50 letters sent to potential sponsors received a favorable reply. Even his letter to the Parish Pastoral Council of Betis asking for support and permission to shoot some scenes within vicinity of the parish of St. James the Apostle was met with opposition by some members.

One of Layug's masterpieces.

Ultimately, it was Brillante Mendoza who funded more than 75 percent of the total production cost and buffer money supplied by the relatives of cinematographer Diego Dobles that saw the film through to post-production.

In the recent Metro Manila Film Festival, as an entry in the New Wave Category, “Dukit” bagged the major awards: Best New Wave Film, Best Director for New Wave Category, and even got a triple tie for Best New Wave Actors—Bor Oampo, Willy Layug, and Bambalito Lacap.

Last but not least, “Dukit” is this year's Best New Wave Picture. — VC, GMA News

More Videos

Most Popular