ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

Charted territories: the Philippines as depicted in old maps

By PATRICIA CALZO VEGA

The proliferation of satellite imaging and unprecedented public access have made maps available to anyone with an Internet connection, even making amateur cartographers out of netizens intent on marking their personal spaces in collaborative mapping projects. Indeed, young people nowadays have the known world at their fingertips, the thrill and threat of unknown destinations tempered by efficient directions.

It is this very generation that has much to learn from the “Philippine-Spanish Friendship Day Exhibit: 300 Years of Philippine Maps 1598-1898,” organized by the Philippine Map Collectors Society (PHIMCOS) in partnership with the Embassy of Spain and the Metropolitan Museum of Manila.

Forced perspectives

A celebration of Philippine-Spanish relations must necessarily include a retrospective on cartography, the map being a particular vessel and instrument of power, wealth, and knowledge during the Age of Exploration.

Back then, one simply did not exist in the eyes of the civilized world until one has been written about in expedition logs and, more importantly, charted on a map. Working with imprecise instruments and the limitations of human senses, cartographers also relied on their imagination to fill in the gaps of their knowledge, developing an instrument that is an amalgam of scientific process and creative thinking.

In his exhibition notes, Dr. Leovino Ma. Garcia posits that maps “help us find our place in the world… where we are… who we are. Maps teach us about our history and identity. They provide us with a memory and a destiny.”

Arranged in chronological order, the PHIMCOS collection forms a striking narrative of the emergence of the Philippines in the global community. Over a hundred cartographic objects are on display, but there are some maps that bear more than a second look.

The exhibition opens with Insulae Philippinae, which holds the distinction of being the first individual map of the Philippines. Drawn by Petrus Kaerius and published in 1598, the map shows the archipelago “lying on its side.”

The Philippines makes its cartographic debut in Petrus Kaerius’s 1598 map.

It takes a while to shake off preconceived constructions and identify our different islands; indeed, those familiar with Old Dutch would be hard-pressed to recognize the Filipinos described in the accompanying text: “inhabitants without laws (inwoenderen zonder Wetten) who are cannibals (Menscheneeters).”

Insulae Philippinae is a compelling reminder that our reality, the way we situate ourselves in this world, is not constant, and is in fact, a relatively new concept. Subsequent maps adopted the Kaerius illustration, or drew the Philippines in similarly confusing orientations, and it isn’t until the mid-1600s—and the emergence of better instrumentation—that the familiar vertical orientation of the Philippines surfaces.

Transaction completed

Such is the influence inherent in what Garcia calls the “cartographic transaction.” Maps undertake three layers of representation: the measurement, visualization, and narration of space.

As the cartographer quantifies the physical landscape through scientific means, he also paints an image of these societies through creative flourishes: an elaborate cartouche symbolizing the institution that commissioned the map, an illustration evoking pride of place or religious faith, or distinct markings that indicates the map’s purpose, an asset for trade or instrument of conquest.

Taken together, these elements form a narrative of the geographic, socioeconomic, and political forces that shape these spaces.

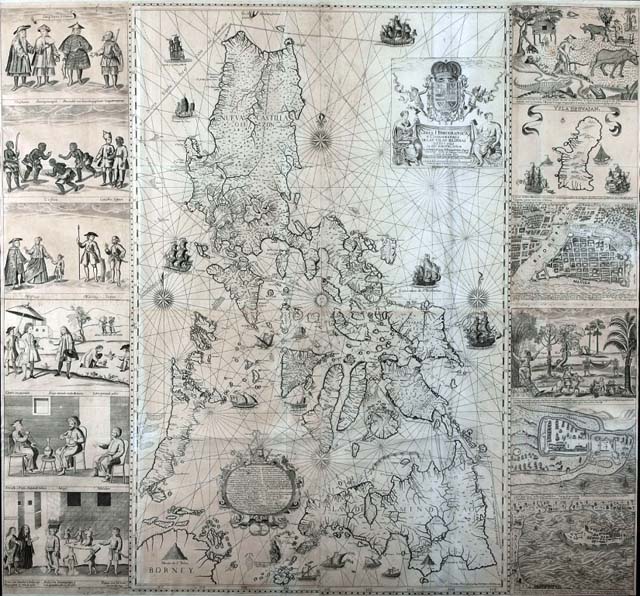

One example of a successful cartographic transaction is the 1734 Carta hydrographica y chorographica de las Islas Filipinas by the Jesuit priest Pedro Murillo Velarde, who was chosen by Governor-General Fernando Valdes Tamon to fulfill the 1732 Royal Order decreeing the creation of an official map of the Philippines.

More fun in the Philippines, circa 1734. The Murillo map served as the standard for Philippine cartography in the decades that followed.

The Murillo map was distinguished by the depth of its geographic detail, making it a very useful guide for navigation and following the trade routes. It is framed by 12 vignettes of everyday life in the islands, its inhabitants, and key destinations.

And as if to further emphasize the success of the colonial project, the map’s inset text describes Filipinos in a glowing manner of a master exceedingly pleased with the improvement of his servants, a far cry from the disdainful tone of the Kaerius map text: “[Filipinos] are well-built, have fine features, and are dusky in complexion. They become good writers, painters, sculptors, blacksmiths, goldsmiths, embroiderers, and sailors.”

Murillo’s observations were not unfounded; his cartographic vision was executed by two talented Filipino craftsmen, Nicolas dela Cruz Bagay and Francisco Suarez.

Looking for Panatag Shoal

Murillo’s representation of the Philippines was widely circulated and copied in atlases and other publications. This fact in itself is of little importance, save for one detail that is of particular interest to us today. A few inches off the engraving of the Zambales coastline is an enclosed group of dots labeled Panacot, or what is now more commonly known as Panatag (Scarborough) Shoal.

A number of opening night guests were preoccupied with spotting the controversial island formation on the maps on display; such visitors were easy to identify, standing two or three to a group, peering closely at a map, and engaged in animated discussion. Indeed, one might make a game of it while viewing the exhibit.

“Scarborough,” taken from a British trade frigate that sank within the vicinity, is the latest of the shoal’s appellations; in addition to Panacot, it is also identified in other maps as Bajo de Masinloc, after a nearby coastal town. Be that as it may, the map yielded by the 1792 Malaspina Expedition, Felipe Bauza’s Carta General de Filipinas, includes all common names for the shoal.

One of the expedition’s commanding officers, Alessandro Malaspina, had previously undertaken a commercial circumnavigation of the world in behalf of the Royal Philippines Company, the organization tasked to oversee the country’s international trade. Similar in intent to Captain James Cook’s voyage, the Malaspina Expedition sought, in behalf of the Spanish government, to carry out a scientific expedition of Spain and its numerous colonies.

That the Bauza map includes Panatag Shoal is an indication that the expedition identified it as part of Philippine territories, one worthy of further study and exploration. And while heritage waters may not be the primary reason stated for our claim over this disputed territory, these cartographic references from the past show that our interest in the shoal goes beyond the economic gains that it may bring, but is rooted in our deep-seated desire to respect our heritage.

Mapping the future

The latter portion of the exhibit is dedicated to Manila Bay and its vicinity, mapped by cartographers of various nationalities.

The cosmopolitan perspective of these maps is refreshing and encourages the viewer to experience all that Manila, then and now a melting pot of peoples and cultures, has to offer. It is in truth a fitting finale to an exhibition that demands a closer investigation of our past: an invitation to explore the possibilities at hand and welcome the future with a positive outlook. –KG, GMA News

The Philippine-Spanish Friendship Day Exhibit Three Hundred Years of Philippine Maps: 1598-1898 runs until July 31, 2012 at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila.

More Videos

Most Popular