My memories of tikoy, that gooey Chinese delicacy made from rice flour and sugar that Pinoys and Tsinoys cannot have enough of every Chinese New Year, are inextricably linked to the late cartoonist and politico-social satirist Severino "Nonoy" Marcelo. Sometime in the second semester of 1982 at the University of the Philippines, my writing partner Estela Padilla and I decided to interview Filipino cartoonists like Nonoy, Larry Alcala, Rox (or was it Mon Lee, who whipped out a picture of a naked Tetchie Agbayani, the Filipino actress who was featured in Playboy) and Zaldy Zuño (creator of Tibo, the much-loved mascot of the UP Diliman campus paper Philippine Collegian) for an English term paper. We asked the artists to draw original samples of their work on our cover folder which, alas, our English professor never gave back (it is worth millions in sentimental value to us).

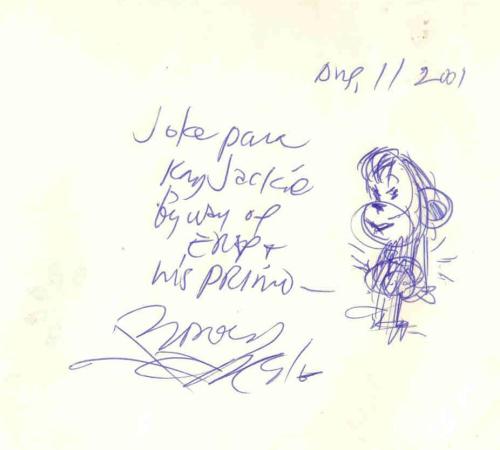

Nonoy Marcelo’s iconic bubwit comes with the dedication “joke para kay Jackie by way of Erap and his primo."

Anyway, when we were asking Nonoy how he generates his ideas, he cited our gift (

tikoy, since it was close to Chinese New Year) as an example. He said he could use the

tikoy and have Estela and I as his “bubwit" characters swinging Tarzan-like from one

tikoy strand to another. I don’t recall now the order of our appearance in his comic strips that were published in some of Manila’s broadsheets. It was always sometime before or after the Chinese New Year because I made

tikoy-giving some sort of an annual ritual after 1982. But I vividly remember that there was a

"singkit" (slant-eyed)

bubwit (as he called his characters in Dagalandia) with my name written beside it and a

"mapungay" one with Estela’s name scrawled beside it. And yes, he did use

tikoy as a Tarzan prop and had us swinging from one

tikoy strand to another, trying to get away from Boss Myawok or stealing food from a table. Sometimes, our names would appear as wall graffiti. I always marveled at his wit and the speed with which he communicated, jumping from one topic to another that did not seem to make sense initially, until he puts a clincher at the end. "Anak ng Kuwago" - that was Nonoy for you. His UP Bliss unit was always a sea of chaos with magazines, books, cigarette butts, pencils, papers, half-eaten sandwiches, stained coffee cups and who knows what else, thrown willy-nilly. What captivated me the most were the swags of glistening cobwebs on the walls and windows, which I was often itching to sweep away. However, it gave his home so much character and drama (I often think it would have also triggered maternal instincts in his girlfriends) and was probably a source of inspiration for one of his most popular strips, Ikabod Bubwit -- that imaginary Mouseland called Dagalandia of his which was actually a candid and satirical commentary of Philippine society, as seen through the eyes of the mice-characters he christened

bubwits. Nonoy ’s wicked humor seemed boundless. Consider this account from writer Joan Orendain, published by the Philippine Daily Inquirer on October 23, 2002, a day after he died. "Baon money expended on cigarettes, Nonoy and the future Caligula, Aling Otik and one or two others would forage for food, more often than not in Funeraria Paz on Azcarraga, today's Claro M. Recto. In the 1960s, food in funeral parlors was to be found only at very wealthy Chinese wakes. Nonoy's instructions were to walk in together, head straight for the bier, pray in earnest for our host -- for one strange reason or another, always male -- then head to the back pew where flowed largesse for the hungry. Sometimes there was a pack of cigarettes apiece for us on the way out, with no one the wiser for having fed scavengers."

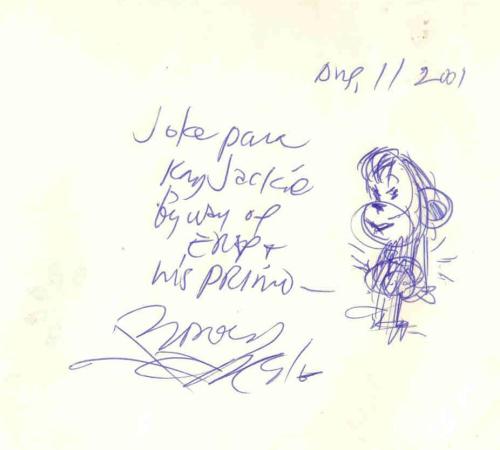

Nonoy Marcelo and the author at the artist’s chaotic BLISS lungga in August 2001.

Nonoy’s generosity is also legendary. An article in the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism’s “i" magazine Oct-Dec. 2002 issue after Nonoy died had this to share: "Nonoy was generous to a fault. He always had some hanger-on hovering around him, someone he sheltered and fed and somehow made useful. Young cartoonists were drawn to him like a magnet, reveling in his wit and his generosity. In the early days of i, he always had this burly companion around. As far as we could tell, all he did was sleep on the office couch — and snore, loudly. In the wee morning hours while we worked, Nonoy would join him on the couch, and sometimes, they would sleep together arm in arm, snoring in unison. "Strays — human and otherwise — found in him a sympathetic and helpful friend, and maybe also a fellow traveler of sorts, sensing in the cartoonist a restlessness and unsettledness that matched their own. This was somewhat strange because Nonoy, especially in the last years of his life, rarely left his apartment, rarely even left his room, even if he had a vagabond soul. "In the months before he died, his son Dario recounted, Nonoy offered a room to a neighbor who had been evicted from her unit at the U.P. BLISS, the rundown government housing project in Diliman, Quezon City. Soon afterward, the neighbor brought her children to stay with her, and later, her good-for-nothing husband. Finally, even the family dog joined the entourage of strays who had made Nonoy's cluttered apartment their home. Such laidback generosity was typical of Nonoy, who once left his own apartment because he could no longer work there after the woman he was then living with brought along various relatives to stay with her." I remember talking to Nonoy after I had already graduated from college about how we could use his cartoon characters and license them out for a line of products including greeting cards, notebooks, T-shirts, and comic books. It turned out he had already done some of them, including a long-playing album and a movie based on his strip Tisoy. He was always ahead of his game and time. In August 2001, I visited Nonoy a couple of times. He looked so different: thinner, with grayer hair. He was wearing a rock-themed black t-shirt. I commissioned him to draw a caricature as a gift to my in-laws. The only payment he asked from me was that I buy his painting supplies, and only because he was running low on them. I think the tab came to about P1,500 which is essentially nothing compared to the masterpieces he was making for me. With only a couple of pictures to rely on, Nonoy came out with a painting so darn good you would have thought the subjects sat for it. His humor never deserting him, he drew my in-laws in a western outfit, since he knew I was already living in Texas with my son, holding one of the Philippines’ iconic candy bars (which my husband’s family owns and thus shall remain nameless) as a rifle of sorts.

The author’s in-laws and son are brandishing a popular Philippine-made chocolate bar as “dos por dos" and pistols in this drawing by Nonoy Marcelo.

I asked him to draw another set of bubwits for a kindhearted sister-in-law but unfortunately, this illustration got misplaced when she moved house. My sister-in-law is now searching every nook and cranny for her original Nonoy drawing. (My own stash of “ikabod bubwit" comic strips suffered a worse fate. When my family moved to a new place years ago, they unknowingly threw away all my earthly treasures which included the articles I wrote for a couple of publications and my precious copies of comic strips that Nonoy drew of me and Estela. I had proudly cut them from broadsheets and showed them off to friends in the Philippine Collegian.) Also during that visit, Nonoy told me he had just won the Centennial Honors for the Arts award given by the Cultural Center of the Philippines, the only cartoonist thus honored. He said it was better to win this award, unlike the national artist award “since this happens only once every 100 years." In her profile of Nonoy, Orendain said that the award read: “Marcelo's works merge political issues with popular forms in drawing a commentary on Filipino society, especially during a period of heightened state oppression. "Because his cartoons represent the temper of the times, chronicling the national experience especially under the dictatorship, the Parangal Sentenyal sa Sining at Kultura is hereby conferred on this 2nd day of February 1999 on Nonoy Santos Marcelo." Nonoy showed me some of the pages of a book on Malabon he was working on, all rich in detail with elaborate calligraphy. He said former President Joseph Estrada also traced his roots from Malabon and that he and Nonoy were, in fact, cousins! I cannot remember now how they were related, but it seemed to be on the maternal side of Estrada so they called each other

primo (cousin in Spanish), even after Nonoy lent his artistic hand to the people power movement that toppled the popular actor-president. During my visit, Nonoy asked me to buy him some

mariachi (the traditional Mexican) music and some more black t-shirts with the images of rock stars. I thought I did but I have a hard time recalling how I sent the goods. When I learned a year later that he had died from complications of diabetes, I felt sick because my husband who is an endocrinologist specializes, among other things, in diabetes. If only Nonoy had told me. Nonoy passed away at the Chinese General Hospital on October 22, 2002 at the age of 63 (some accounts had his age at 62). He was cremated and his ashes put to final rest in his beloved Malabon, according to the International Cartoon Center website. Years later, I have never been able to look at

tikoy the same way again. Happy Chinese New Year to you Nonoy, and say hi to my dad before you chew that

tikoy. –

YA/GMANews.TV The author is a journalism graduate who currenty resides in Brownsville, Texas and contributes regularly to a Filipino-Chinese magazine in Manila. She is a lifelong Nonoy Marcelo fan.