Coronavirus can transform pancreas cell function; Certain genes may protect an infected person's spouse

The following is a summary of some recent studies on COVID-19. They include research that warrants further study to corroborate the findings and that have yet to be certified by peer review.

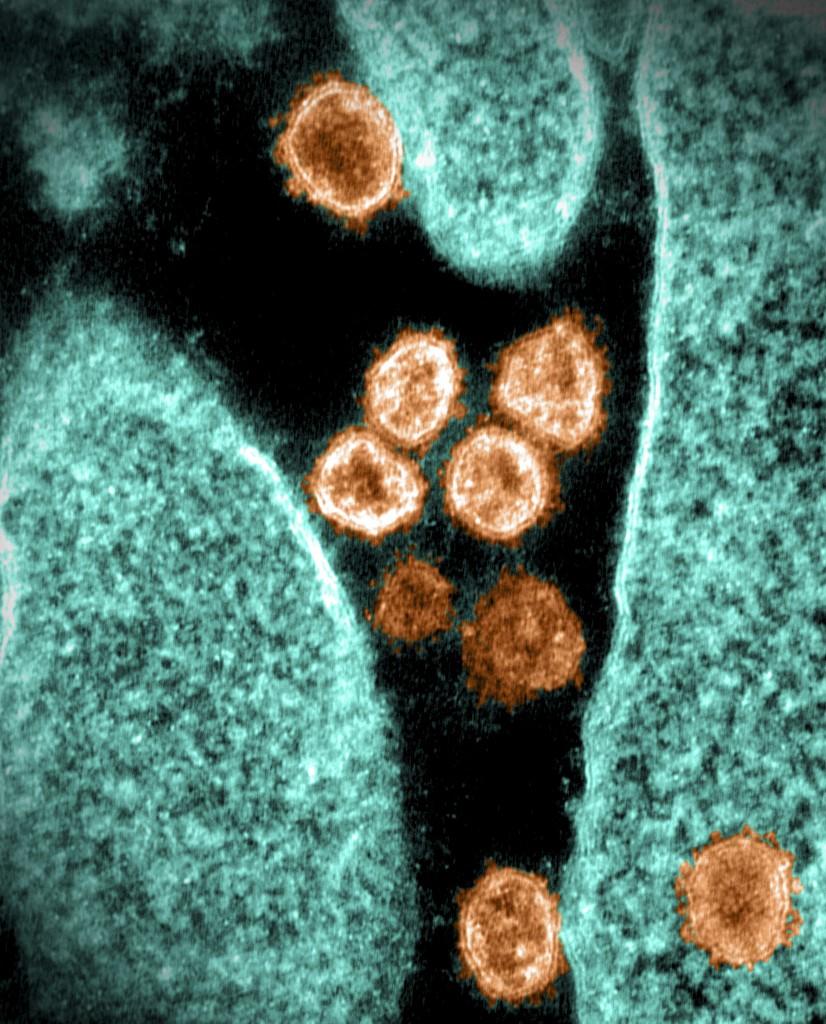

Coronavirus transforms pancreas cell function

When the coronavirus infects cells, it not only impairs their activity but can also change their function, new findings suggest.

For example, when insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas become infected with the virus, they not only produce much less insulin than usual, but also start to produce glucose and digestive enzymes, which is not their job, researchers found.

"We call this a change of cell fate," said study leader Dr. Shuibing Chen, who described the work in a presentation on Tuesday at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, held virtually this year.

It is not clear whether the changes are long-lasting, or if they might be reversible, the researchers noted earlier in a report published in Cell Metabolism.

Chen noted that some COVID-19 survivors have developed diabetes shortly after infection.

"It is definitely worth investigating the rate of new-onset diabetes patients in this COVID-19 pandemic," she said in a statement.

Her team has been experimenting with the coronavirus in clusters of cells engineered to create mini-organs, or organoids, that resemble the lungs, liver, intestines, heart and nervous system.

Their findings suggest loss of cell fate/function may be happening in lung tissues as well, Chen, from Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, told Reuters.

Certain genes may protect an infected patient's spouse

A study of couples in which both partners were exposed to the coronavirus but only one person got infected is helping to shed light on why some people may be naturally resistant to the virus.

The researchers had believed such cases were rare, but a call for volunteers who fit that profile turned up roughly a thousand couples.

Ultimately, they took blood samples from 86 couples for detailed analysis.

The results suggest resistant partners more often have genes that contribute to more efficient activation of so-called natural killer (NK) cells, which are part of the immune system's initial response to germs.

When NKs are correctly activated, they are able to recognize and destroy infected cells, preventing the disease from developing, the researchers explained in a report published on Tuesday in Frontiers in Immunology.

"Our hypothesis is that the genomic variants most frequently found in the susceptible spouse lead to the production of molecules that inhibit activation of NKs," study leader Mayana Zatz of the University of São Paulo, Brazil, said in a statement.

The current study cannot prove this is happening, she added. Even if the findings are confirmed with more research, the contributions of other immune mechanisms would also need to be investigated, the researchers said. -- Reuters