Giant shipworm discovered in PHL

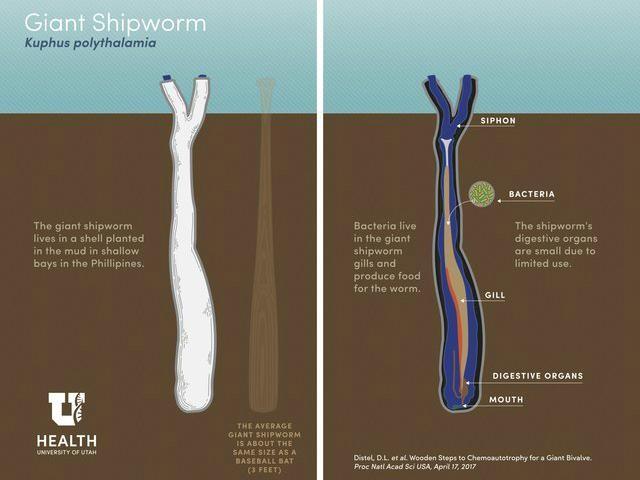

Ever heard of the giant shipworm? Probably not. After all, its description seems to be the stuff of myth: a worm measuring 3 to 5 feet long that spends most of its life in a hard shell resembling a tusk.

Well, it is myth no longer, as scientists have just found live specimens of the giant shipworm, or Kuphus polythamia, right in the Philippines.

The shipworm is, in fact, not a worm, but a rare species of bivalve or mollusk, a group that includes mussels and oysters. To be more specific, it is a type of saltwater clam. First documented in the 1700s, the shipworm was partly responsible for the sinking of ships, thanks to its natural tendency to eat wood.

The Kuphus polythamia is slightly different from the regular, ship-sinking shipworms. While scientists have known of its existence for years courtesy of fossils, it is only now that they’ve been able to study it firsthand.

The recent specimens were discovered in Mindanao, Philippines, vertically planted head-down in the base of a lagoon, where they feed on marine sediment and mud. Though the site, which was once an area used for log storage, boasts an overwhelming stench, the researchers were able to gather five living giant shipworms for analysis.

Packing the creatures into PVC pipes, the team brought their cargo to the University of the Philippines.

“We really did not know what to expect,” Daniel Distel, a research professor and the Northeastern University Ocean Genome Legacy Center director, told Seeker. “Most clams are white or beige or pinkish inside.”

‘Like an alien creature’

Margo Haygood – a University of Utah College of Pharmacy medicinal chemistry research professor and a colleague of Distel – described what it was like first laying eyes on the animals.

“We turned the pipes upright and filled them with seawater and airstones and put the animals in to acclimate," she stated. "Before long, I looked into the pipe and could see a strong jet of water coming out of the animal’s siphon. It was alive!”

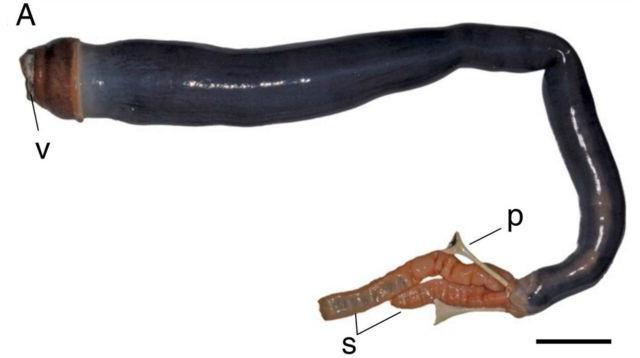

She added: “The animal inside is dark gray, shiny and floppy. It looks like an alien creature.”

“It was really quite amazing,” Distel stated, speaking about his experience opening the creature’s tube-shaped shell. “I didn’t even have any idea how to open it, but I thought: ‘Carefully.’ ”

Distel admitted being shocked at the animal’s color. “Most bivalves are greyish, tan, pink, brown, light beige colors. This thing just has this gunmetal-black color. It is much beefier, more muscular than any other bivalve I had ever seen.”

According to the scientists from the US, France, and Philippines who have examined the organism, it is the longest bivalve in existence (that we know of). It is slimy and black, with a big ugly head and a tail composed of two siphons. One siphon draws in water, while the other expels it.

The organism secrets a substance to create its tube shell, which is composed of calcium carbonate. Additionally, it creates a hard cap as a head covering. The creature’s growth, which compels it to submerge itself even deeper into the mud, urges it to reabsorb said cap.

“If they want to grow, they have to open that end of that tube, so somehow dissolve or reabsorb that cap on the bottom, grow, extend the tube down further into the mud, and then they seal it off again,” Distel told The Guardian.

Living on bacteria and fart gases

Unlike the usual wood-munching shipworm found in oceans, the survival of the Kuphus polythamia depends on hydrogen sulfide and a special type of bacteria.

Hydrogen sulfide is a compound which you can find in human flatulence and rotten eggs, and which can also be flammable, corrosive, and poisonous in large volumes.

The bacteria, which make a home in its gills, burn the hydrogen sulfide in “the same way we burn carbohydrate or sugar to make energy,” said Distel. The Kuphus polythamia then feeds on the sugar.

Living in the mud, which is rich in organic substances such as the stinky hydrogen sulfide, provides the animal with an endless supply of life-sustaining nutrients.

Thanks to the creature’s strange diet, is digestive system is smaller than the usual shipworm’s.

The evolution of giants

It is not known how the giant shipworm evolved to be this way, but its size is indicative of a healthy diet.

“Gigantism is usually an indication of ample nutrients,” stated Distel.

In contrast, it’s increasingly becoming more difficult for its wood-munching, ocean-dwelling cousin to find food, given how humans are no longer using wooden ships to sail the seas.

“Most wood gets in the oceans via erosion of coastal forests and riverbanks,” said Distel. “People like to clear forests away from coasts and riverbanks so they can build homes, businesses and resorts. We also like to build dams and have dammed most of the great rivers of the world. As a result, a lot less wood makes it to the sea.”

As wooden ships have contributed to the spread of shipworms to various countries, it is possible human activity helped the creature find its way to the shallow bays of the Philippines, where it then evolved into its current form.

Shipworms have even become part of human diet in some places. Its taste is described as “a little more earthy-tasting” than regular clams.

While Haygood believes the shipworm “is valuable just because it's so strange and marvelous,” she also claims these organisms have “potential as sources of industrial enzymes for converting cellulose to sugar and for new antimicrobial drugs.”

'Like finding a dinosaur'

Distel believes the team’s find to be extremely remarkable. “To me it was almost like finding a dinosaur – something that was pretty much only known by fossils,” he said.

The researchers would likely have never found the Kuphus polythamia had they not chanced upon a Philippine documentary, shared on YouTube, about divers who collected the creatures. To prevent shell collectors from disturbing the site, the animals’ location remains a secret.

TV presenter, biologist, and Ugly Animal Preservation Society president Simon Watts was happy at the discovery. “It might well be monstrous, but that does not mean that it isn’t marvelous,” he stated, adding that the Kuphus polythamia evolved to survive in a “pretty disgusting” environment. “If you are down living among murky dirt, then aesthetics are surely not your number one priority.”

The study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS). — TJD, GMA News