The first thing I noticed about Mauro “Malang” Santos when I first met him was his eyes. They were smiling eyes, and with them, he looked like a gentle person, like someone's grandfather.

We were both on the staff of Lifestyle Asia magazine back in the early '90s. He was the creative director and I was the lone staff writer. Once in a while, he would drop by the office wearing a simple shirt and always clutching something — envelope, proofs, a book, a magazine, a sketchbook — and trade jokes with our executive editor Nestor Mata or editor-in-chief Jullie Yap-Daza, or Pocholo Romualdez, executive editor of Taipan magazine.

The smiling eyes were what struck me first, because they were in stark contrast to Mr. Mata's piercing eyes and gruff and stern demeanor.

“O ano, nag-abroad ka na naman? Talaga nga naman o,” he would say to me, and would head to the art room before I could protest that it's been a long time since he dropped by, thus the foreign trip was ages ago. This happened maybe twice or thrice.

Part of my work was to cover the art scene, so I would bump into him at art exhibits. During his birthday month of January, he would almost always have an exhibit and it was a joy for me to view his works and write about them. His works were always happy and optimistic, and I was charmed by his depiction of women in butterfly sleeves tending to sari-stores with “garapon” galore in front of them. “Ang ganda! Walang angst,” I told him once. “Angst? Si Ang Kiukok, maraming angst!” he said, laughing.

Malang told me that he always draws the woman in terno sleeves because she reminds him of his mother Justina, who would be dressed up like that when he was small.

They had a sari-sari store on Avenida right beside his father's pharmacy, and Malang's task as a young boy was to bring out those large jars of candies and biscuits to the store every morning and bring them back into the house when it was closing time.

Even as a young kid, he loved to draw. And so his parents enrolled him in art lessons with artist Teodoro Buenaventura who was their neighbor. He studied at the UP School of Fine Arts for college, but dropped out before the first term was over, saying he was bored.

Malang then went to work as a cartoonist for the Manila Chronicle and started painting at the prodding of his boss, H.R. Ocampo.

His first one-man show was in 1962 at the Philippine Art Gallery owned by Lydia Arguilla. She included him in the “Twelve Artists in the Philippines—Who’s Who” list. Art lovers and collectors took note of him and his exhibit was sold out. This was the start of a prolific career in painting, and he never skipped a day to paint except when he became ill late in life.

Despite his success, Malang remained a humble and approachable person. When we discovered that he would take his breakfast daily at McDonald's on Quezon Avenue, my partner and I would go there as often as we could, and over pancakes and coffee talk about art and life.

His son Soler and daughter-in-law Mona would join us after about an hour, then Malang would leave us to go across the street to National Bookstore to look at books and art supplies before going back to his studio to paint.

But it was not all art that we would talk about. One time, when there were just the two of us, he asked me, no, he chided me, for leaving a relationship. “Ikaw talaga, o. Sabi sa Bible, how many times should you forgive? Seventy times seven!” he said. “Pero kasi naman, Mr. Malang, may iba,” I said. “Alam ko,” he said, like a father who knew all along what was happening to his children.

Family was important to Mr. Malang, so much so, that he always kept every member close as much as he can. He lived somewhere near West Avenue in Quezon City with his children and grandchildren.

At Marisan Building on West Avenue—named after his late wife Mary Santos—he would drop in and check on his children while they worked in the various family businesses housed therein: West Gallery, a frame shop, a souvenir shop, Video 48, among others. This he would do while taking a break from painting at his studio on the top floor.

When I worked for him at Art Manila Newspaper, the monthly publication he put out for the art community, he would drop by often at my desk at Marisan to pitch stories or chat about art or life. He always carried a book with him, and I would always ask to see what he was reading that day.

Malang, though gentle, could be very opinionated and stubborn. This got him into strong discussions and rifts with other artists. I experienced this side of him when, after I put one issue to bed, he had a “remat” done without telling me. He put in an article I haven't even seen. As editor, I was a bit incensed when I found out, and left the publication in a huff.

But one cannot make tampo for long with Mr. Malang, because, well, he was like a father you love despite shortcomings.

When I saw him one time hunched over a thick hardbound book at McDo, I asked what he was reading and he showed it to me. It was “The Answer,” a New Century Version of the Bible with added features: excerpts from the writings of well-known personalities and authors. “Uy, okay ito ha,” I said. One day, Mona handed me the book covered in plastic with a blue Post-it note: “For Ate Karen. Malang.”

I suspect he was the sender of Christian messages printed on a sheet of bond paper, placed in a letter envelope with my name outside. I think I would get one every month via slow mail for maybe six months. No return address. I had a hunch it was him when one of those papers had some additional text written by hand and the penmanship matched his.

When I moved on to another magazine, I saw less of Malang. However, I would try to see him and write about him once in a while, or he or Soler would ask me to write about an upcoming exhibit. In one of our later interviews, I asked him how he wanted people to remember him. He said, “a Christian artist.”

For Malang, God was the source of all he had—his life, family, art, strength, peace, joy, everything. Before the break of dawn, he would pray and seek his Maker first and read the Bible before picking up a paintbrush.

In the last few years, Malang stayed mostly at home due to vertigo. His memory was also failing due to suspected Alzheimer's disease. But I was grateful for that one time I dropped by Marisan on a whim to see an ongoing art exhibit and have a snack at the coffee shop downstairs. His daughter Sarah told me Malang was right outside, inside the car. Sarah motioned for him to roll down the window and told him I was there. I waved, and he waved back, but in my heart I was not sure he remembered me.

From Soler and Mona I would gather info over time that Mr. Malang has stopped painting and just stayed in bed all day. My heart sank. I encouraged them to try playing music for him to lift his spirits.

Last Saturday morning, Mr. Malang breathed his last. He was 89. Though grieving, his family is grateful that his physical suffering is now over.

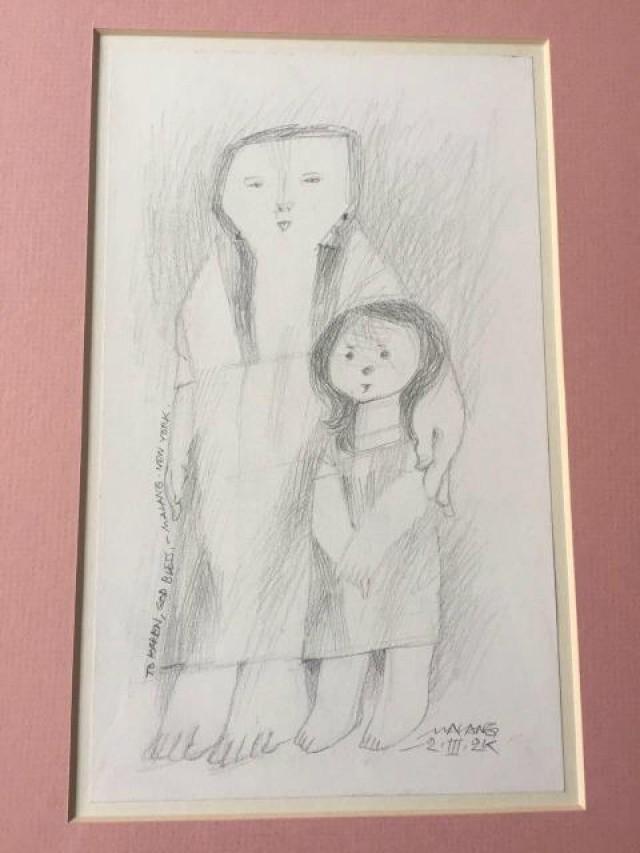

At the wake last Sunday at Arlington Memorial Chapels on Araneta Avenue in Quezon City, I was surprised to see not a casket but an urn. “Na-cremate na pala,” I told Mona. She nodded, saying it would be good if people's last memory of Mr. Malang was when he was still healthy, strong, and alive. “'Yan, ganyan,” Mona said, pointing to the portrait beside the urn.

I looked, and yes, it was the Mr. Malang I knew. The one with the smiling eyes. And so as I write this, I see his smiling face, as if saying again, “O ano, kumusta? Nag-abroad ka na naman? Talaga nga naman, o.” I'd say no, Mr. Malang, I am just here, but you probably can see that already. Say hi to mom for me.—LA, GMA News